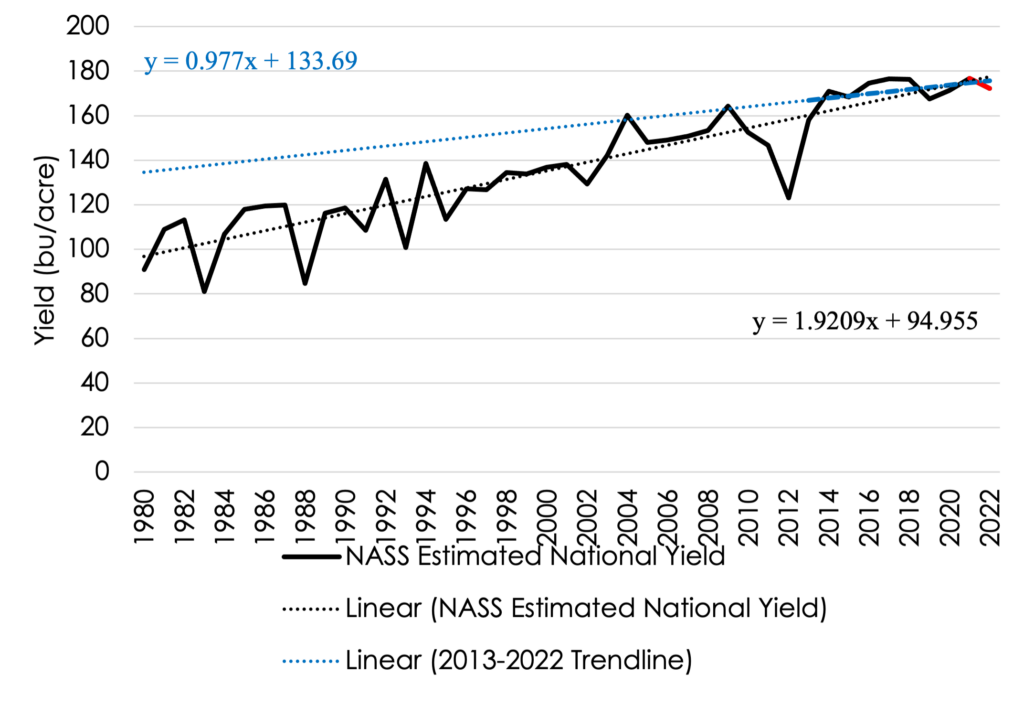

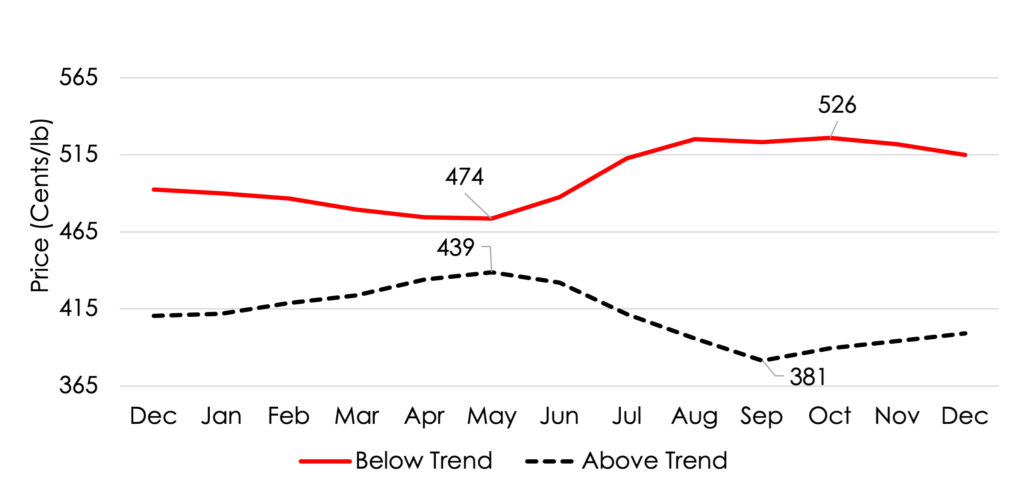

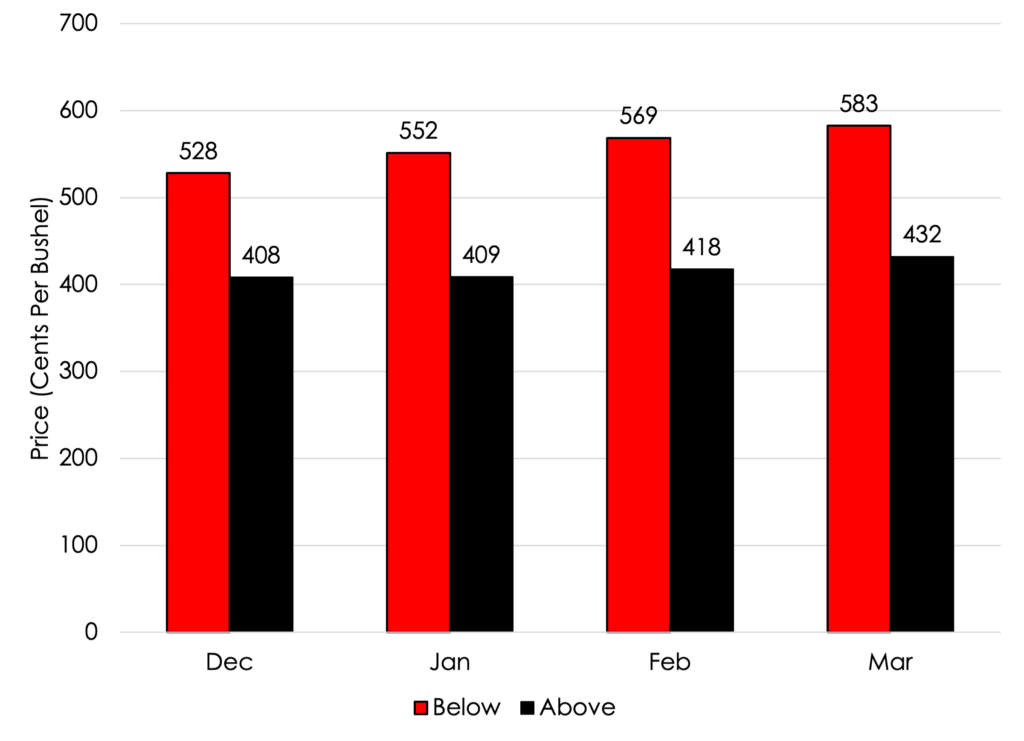

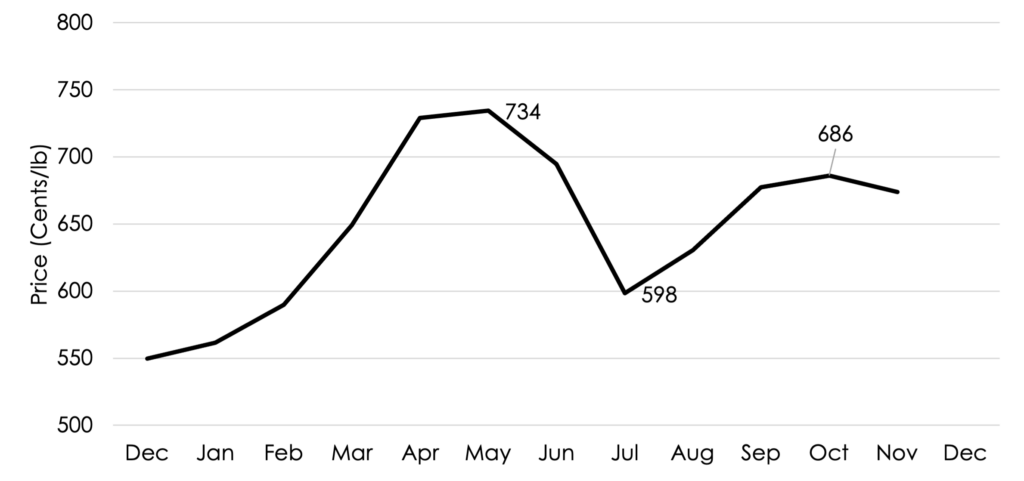

The 2021 and 2022 corn and soybean harvest futures prices for November and December had increased trading ranges (Figures 1 and 2). November 2022 soybean futures, from November 1, 2021, to contract expiration, had a trading range of $3.81 ($12.02 to $15.81; Figure 1). December 2022 corn futures, from December 1, 2021, to contract expiration, had a trading range of $2.23 ($5.43 to $7.66; Figure 2). Tight U.S. stocks, the Russia-Ukraine conflict, global inflation, supply chain disruptions, and drought in the U.S. and South America have propelled prices higher but have also increased volatility. In 2021 and 2022, the November soybean contract had 45 and 74 trading days, respectively, with a 20-cent up or down move. For the previous five years, the November soybean contract had a total of 64 days with a 20-cent up or down move. Similarly, the 2021 and 2022 December contracts had 49 and 65 trading days, respectively, with moves of 10 cents up or down. The previous five years had a total of 54 trading days with a 10-cent move.

Figure 1. November Soybean Futures Contract Price from November 1 to Expiration, 2010-2023*

* November 1, 2022, to January 19, 2023

* December 1, 2022, to January 19, 2023

What will 2023 bring for soybean and corn futures prices and how should this affect producers marketing and risk management decisions? As of January 19, the 2023 average daily closing futures prices for corn and soybean harvest contracts were near the top of the 2010-2022 price range – November soybeans averaged $13.89 and December corn averaged $5.98. As such, it would be reasonable to think that prices have more downside risk than upside potential, but this will be largely determined by weather. Additionally, there remains a tremendous amount of uncertainty in the global economy, geopolitics, and U.S. and global production for the 2023 crop year. It is likely that volatility will continue in corn and soybean futures markets.

What should producers do? Protecting against downside risk seems logical given current market conditions. This can be accomplished using numerous marketing tools (futures, contracts, options, etc.). Put options provide an opportunity to establish a futures price floor. There are several strategies that producers can consider – at-the-money put options, out-of-the money put options, or a combination of put and call options to reduce premium expense. Each producer will have different risk tolerances, so there is no one size fits all approach. The key is to evaluate strategies and choose the one that makes the most sense for your individual circumstances. A simple example of an out-of-the money put option strategy (current December corn futures are trading at $6.00) is:

Buy a $5.50 December Put Option for 27 cents setting a $5.23 futures floor. This removes 87% ($5.23/$6.00) of the futures price risk, while leaving the upside open and the flexibility to set basis at a later date.

For producers interested in learning more about using futures and options to manage risk in grain and oilseed markets, the CME group has a self-study guide that explains several strategies. The current uncertainty and volatility in corn and soybean futures markets necessitates downside price protection. Producers should evaluate strategies that can remove price risk for the 2023 crop.

References

Barchart.com. December Corn and November Soybean Historical Daily Closing Prices. Accessed at: https://www.barchart.com/futures/quotes/ZCZ23/historical-download and https://www.barchart.com/futures/quotes/ZSX23/historical-download

CME Group. 2019. Self-Study Guide to Hedging with Grain and Oilseed Futures and Options Accessed at: https://www.cmegroup.com/trading/agricultural/files/pm255_self-study-guide_hedging_en_2019.pdf

Author: S. Aaron Smith

Associate Professor and Extension Economist

University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture

Smith, Aaron. “Trading Ranges and Volatility for November Soybean and December Corn Futures Prices.” Southern Ag Today 3(4.1). January 23, 2023. Permalink