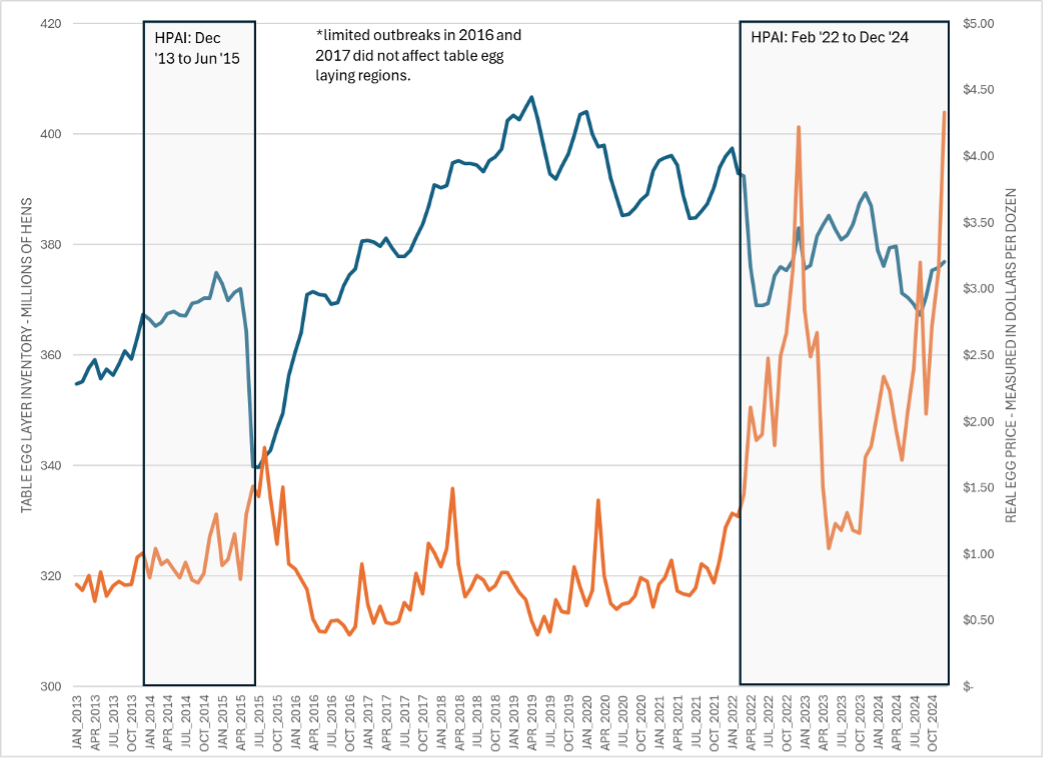

Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) has been in the news regularly due to high egg prices and limited quantities of eggs on grocery store shelves. These effects have mostly been driven by large numbers of table egg layers depopulated due to HPAI (see Figure 1). Depopulation is “the rapid destruction of a population of animals in response to urgent circumstances with as much consideration given to the welfare of animals as practicable” (USDA APHIS, 2022). Depopulation is a key response to HPAI and other highly contagious diseases for two reasons. First, HPAI is deadly to poultry, causing high rates of death within a matter of days and rapid spread through a flock given even minimal contact. Second, when HPAI is allowed to circulate in poultry populations it can easily spread to other farms and potentially to farm workers. Despite rapid depopulation of farms where HPAI is detected, ongoing exposure threats exist due to virus circulation in wild bird populations.

Currently, HPAI circulates in all four wild bird flyways (Pacific Flyway, Central Flyway, Mississippi Flyway, and Atlantic Flyway) that extend across the Western Hemisphere and overlap into the Eastern Hemisphere. For example, the Pacific Flyway overlaps the East Asian and Australasian Flyway. This overlap created the origins of the 2014-2015 Eurasian H5N8 HPAI outbreak in the U.S. from migratory birds moving along the Pacific Flyway (USA APHIS, 2016). HPAI strains mutate rapidly, and most recently in 2024 H5N1 HPAI spilled over into dairy cattle. However, dairy cattle are less susceptible with much lower rates of inflection within herds (<10% of cows), less significant clinical signs, and very low rates of death (AVMA, 2024). This has allowed dairies to isolate and quarantine infected dairy cows until they recover and can be cycled back into production, barring any complications in the cow’s recovery. As a result, depopulation has not been pursued for HPAI control in dairy production. Rather there is a greater interest in the use of vaccination, which is still in the development process and is not commercially viable at this time.

There are other highly contagious diseases for which depopulation would likely be used to reduce disease spread. The first example is foot-and-mouth disease (FMD), which has not been found in the U.S. since 1929 but circulates in wildlife and livestock populations in other parts of the world. Unlike HPAI, FMD has a low rate of mortality. However, FMD has a very high (almost 100%) rate of infection from relatively low exposure and rapid spread through herds. FMD is also a hardy virus that lingers in an environment for some time. For that reason, FMD is another disease for which the baseline response is depopulation of infected animals.

The second example is African swine fever (ASF), which is also highly contagious with high rates of spread, as well as serious clinical signs and high rates of mortality among young pigs. ASF response would also likely involve depopulation of infected herds. The danger of ASF to swine industries was highlighted by the outbreak in China in 2018. China is the largest swine producer in the world, and also the largest pork consumer. The estimates of the Chinese swine herd that died or were depopulated due to ASF were reported as 40.5% with a 39.3% decline in the breeding herd (Ma et al., 2021); for perspective, the 12.3 million head death loss in China’s breeding herd was roughly twice the size of entire U.S. swine breeding herd in that same year (6.17 million head). In the following 2 years, as the herd was rebuilt, China depended heavily on imported pork from a variety of trading partners. Neither FMD nor ASF are zoonotic diseases, with the potential to spill over into humans, and neither FMD nor ASF is currently in the U.S.

Depopulation is expensive, with depopulation costs associated with the destruction of animals, the disposal of contaminated carcasses, and the indemnities to compensate producers for depopulated livestock or poultry. However, this is offset by some benefits, mainly associated with maintaining consumer confidence in the safety of the food supply as well as maintaining access to international markets. For an industry that exports a significant amount of meat or animal product into the world market, the loss of export market share can be very expensive. However, if outbreaks can be constrained geographically export losses can be minimized through the application of regionalization. Regionalization is a general term for allowing trade to continue from disease free areas. Regionalization requires transparent reporting of the disease and eradication measures, which typically includes extensive quarantine, movement restrictions, depopulation of infected premises, and surveillance. Bilaterally, trading countries can place regionalized trade bans of different extents and durations, which could be a control zone within 20 km of an infected herd, a county, or a state or multi-state region. A national trade ban can occur, but is used by fewer countries where proof of geographic containment can be provided.

Most recently, there is discussion of investing in vaccination strategies for highly contagious animal diseases in order to reduce spread and consequently reduce the need to depopulate. There are a few considerations for vaccination to think about. First, a vaccine needs to match the circulating virus well to be effective. This is why viruses that are fairly stable can be effectively eradicated through vaccination. The highly contagious animal diseases mentioned here mutate quickly. A viable vaccine is available for FMD, and the U.S. has invested in a FMD vaccine bank that can be quickly deployed in the event of an outbreak. However, no approved vaccine is currently available for ASF. The threat of HPAI in both poultry and dairy cattle has accelerated the development of vaccines, and the ability to match an HPAI vaccine is improving even with a quickly mutating virus. Licensed HPAI vaccines are not commercially available and there are aspects of an HPAI vaccination policy that are yet to be worked out. For all of the potential benefits, vaccination will likely come at a high cost also.

Trade partners generally will treat eradication or prevention through vaccination campaigns with similar trade bans to outbreaks. This is because vaccination can prevent signs of clinical illness but may not prevent infection. As a result, extensive surveillance requirements are needed to assure that infection is not being spread to areas outside of the vaccination zone through the movements of animals or products. Bilateral discussions with trading partners will be needed to agree to protocols for ensuring disease freedom status. This can be expensive, both in terms of budget and also in terms of trained personnel to track vaccinated animals. If vaccination is expected to be ongoing due to external disease pressure, as is the case with HPAI in wild bird reservoirs, costs will accrue on an annual basis. The logistics of applying a vaccine may be challenging. FMD and HPAI vaccines require two doses to be fully effective, requiring animals to be handled multiple times. In long lived species like cattle, the vaccination must be repeated for protective immunity. Vaccination is unlikely to ever be used to prevent a disease from entering a country due to these expenses and complex policy implications. However, for a disease like HPAI where risk of introduction is ongoing via wild bird exposures, vaccination may well be a viable response strategy.

Figure 1. Table Egg Layer Inventory (left axis) and Real Egg Price Per Dozen Egg (right axis) from 2013 to 2024, with HPAI Outbreaks Highlighted In Each Box

References:

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA APHIS). 2022. “HPAI response: Response goals & depopulation policy” Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/sites/default/files/depopulationpolicy.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA APHIS). 2016. “Final report for the 2014–2015 outbreak of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) in the United States.” Veterinary Services Surveillance, Preparedness, and Response Services Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/media/document/2086/file

American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). 2024. “Avian influenza virus type A (H5N1) in U.S. Dairy Cattle.” Website: https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/animal-health-and-welfare/animal-health/avian-influenza/avian-influenza-virus-type-h5n1-us-dairy-cattle

Ma, M., H.H. Wang, Y. Hua, F. Qin, J. Yang. 2021. “African swine fever in China: Impacts, responses, and policy implications.” Food Policy, 102(102065).

Hagerman, Amy. “Depopulation as a Tool for Highly Contagious Animal Disease Control.” Southern Ag Today 5(11.2). March 11, 2025. Permalink