In 2025, U.S. spirit exports to Canada collapsed as a direct consequence of escalating trade tensions, marking one of the sharpest declines in cross-border alcohol trade in recent history. Prior to 2025, Canada accounted for about 11% of U.S. distilled spirit exports. Between 2022 and 2024, Canadian imports exceeded $250 million annually, making Canada the second-largest market for American whiskey, bourbon, rum, and other distilled spirits (USDA, 2025). In March 2025, Canada effectively halted imports and sales of U.S. wine and spirits in retaliation for tariffs imposed by President Trump on Canadian goods. Provincial liquor boards removed American products from shelves, triggering a dramatic plunge in U.S. spirit exports (DISCUS, 2025). Canada also imposed a 25% retaliatory tariff on U.S. distilled spirits and other products in March 2025, which was lifted in September (Government of Canada, 2025). However, the impact far exceeded what would be expected from a 25% tariff alone, underscoring the severity of the trade dispute.

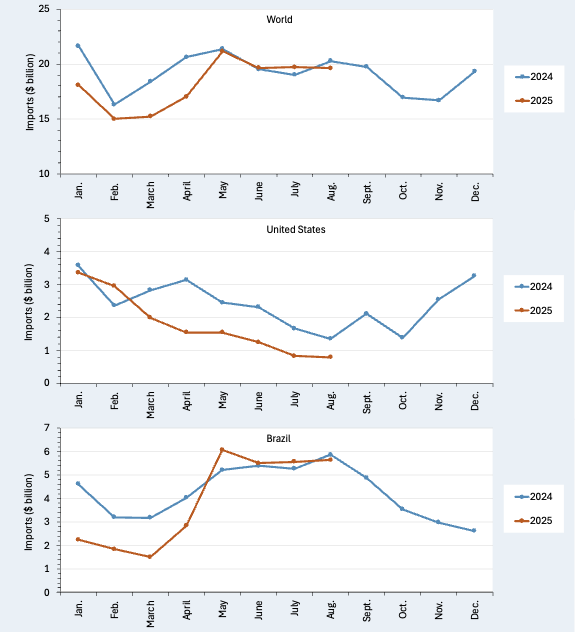

Figure 1 shows monthly U.S. spirit exports to Canada (in million proof liters), comparing the 2022–2024 three-year average with 2025. The data show a sharp and sustained decline in 2025 relative to historical levels. From 2022 to 2024, monthly exports typically ranged between 1.2 and 2.3 million proof liters, peaking during summer months. In stark contrast, exports in 2025 fell dramatically after February, dropping from 1.4 million proof liters in February to just 0.2 million in April, and averaging less than 0.4 million proof liters per month for the remainder of the year. Overall, 2025 marks an unprecedented contraction in Canadian spirit imports from the United States. In terms of value, U.S. spirit exports to Canada averaged over $160 million between March and September in years prior. However, exports in 2025 during the same period were only $35 million (USDA, 2025). Comparing March through September, American distilled spirit sales to Canada were down approximately almost 80% compared to the prior three-year average, underscoring the severe impact of trade restrictions.

Such a steep decline signals fundamental shifts in cross-border alcohol trade that may not be reversed by tariff removal alone. The restrictions on U.S. spirits were not merely retaliatory; they appear to have stimulated domestic production and potentially redirected Canadian consumers toward local and alternative sources. The long-term effects remain uncertain. However, it is noteworthy that imports of oak casks and barrels—essential for aging spirits—rose by 6% during this period (USDA, 2025), suggesting increased investment in Canadian distilling capacity.

Figure 1. U.S. spirit exports to Canada: 2022-2024 and 2025

References

Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS) (2025). Removal of U.S. Spirits from Canadian Stores in Retaliation to U.S. Trade Dispute Resulted in Sharp Sales Decline of U.S. Products, Canadian Products and Total Spirits Sales. https://distilledspirits.org/news/spirits-canada-analysis-removal-of-u-s-spirits-from-canadian-stores-in-retaliation-to-u-s-trade-dispute-resulted-in-sharp-sales-decline-of-u-s-products-and-total-spirits-sales/

Government of Canada (2025). https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/international-trade-finance-policy/canadas-response-us-tariffs.html

U.S. Department of Agriculture (2025). Global Agricultural Trade System. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx

Muhammad, Andrew. “Trade War Fallout: The Collapse of U.S. Spirit Exports to Canada in 2025.” Southern Ag Today 5(51.4). December 18, 2025. Permalink