Although it may be a new year, it brings many old questions, including how the Federal Reserve will manage interest rates in 2026. The Federal Reserve adjusts the federal funds rate, the rate at which banks in the Federal Reserve System lend to one another. Their objective in adjusting rates is to 1) keep inflation low and stable and 2) maintain full employment in the economy. After swiftly raising the federal funds rate in 2022 to combat inflation, the Federal Reserve began lowering its target rate slowly in the second half of 2024. The federal funds rate held steady for most of 2025; however, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the group within the Federal Reserve that sets interest rates, resumed rate cuts at its September meeting. The FOMC implemented additional cuts at its next two meetings in October and December.

Additionally, at the December meeting, the FOMC released its latest economic projections and monetary policy expectations. These projections summarize the views of the thirteen FOMC members on economic growth, unemployment, and inflation, as well as their views on appropriate monetary policy in both the short and long term. Table 1 summarizes FOMC members’ projections for 2026. While FOMC members largely agree on how the economy will perform this year, they differ on how the federal funds rate should change.

Table 1. 2026 Economic Projections of FOMC Members as of December 30, 2025

| Median (%) | Central Tendency (%)1 | Range (%) | |

| Change in Real GDP | 2.3 | 2.1 – 2.5 | 2.0 – 2.6 |

| Unemployment Rate | 4.4 | 4.3 – 4.4 | 4.2 – 4.6 |

| PCE Inflation | 2.4 | 2.3 – 2.5 | 2.2 – 2.7 |

| Federal Funds Rate | 3.4 | 2.9 – 3.6 | 2.1 – 3.9 |

How the FOMC manages the federal funds rate in 2026 will depend on how inflation and unemployment change. All else equal, if inflation rises again, the FOMC is more likely to maintain or raise the federal funds rate. On the other hand, if unemployment increases, the FOMC is likely to lower the federal funds rate and may do so more rapidly than it currently plans. If we take the FOMC’s median projection as its most likely course of action, we expect the FOMC to make a single quarter-point cut to the federal funds rate in 2026. While it may implement this cut early in 2026, during its January or March meeting, it’s more likely that a single cut would occur in the third or fourth quarter of 2026. This would imply a 3.5-3.75 percent federal funds rate to start the year, with a cut to 3.25-3.5 percent at some point between June and December.

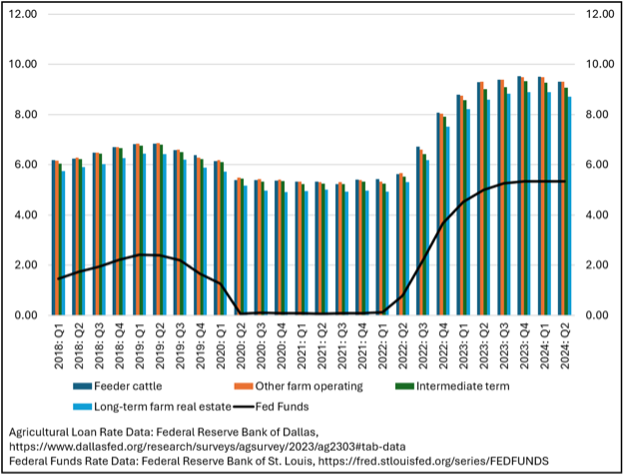

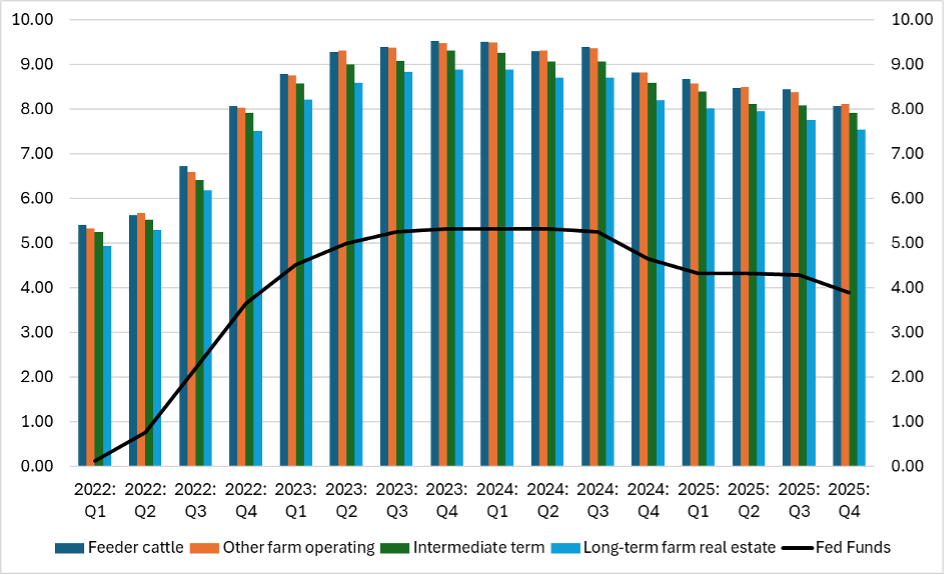

Figure 1 uses data from the Dallas Federal Reserve’s Agricultural Survey to illustrate how the FOMC’s actions affect agricultural lending rates. Ag lending rates tend to move with the federal funds rate and are about 4-5 percentage points higher on average. If this relationship continues, a single quarter-point cut would imply average ag lending rates in the Dallas Federal Reserve District in the mid-to-upper 7 percent range for operating loans and in the low-to-mid 7 percent range for intermediate and real estate loans. However, the actual rate a borrower receives will depend on their relationship with the lender and their perceived creditworthiness.

Figure 1. Agricultural Lending Rates by type and the Federal Funds Rate, 2022-2025

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Federal Funds Effective Rate [FEDFUNDS], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), Agricultural Survey, retrieved from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas; https://www.dallasfed.org/research/surveys/agsurvey.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), December 30, 2025: FOMC Projections Materials, Accessible Version. Retrieved from: https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcprojtabl20251210.htm.

Wright, Andrew. “The Outlook for Interest Rates in 2026.” Southern Ag Today 6(6.1). February 2, 2026. Permalink