We think we can all agree on one thing: we’re all sick of talking about the state of the farm economy. After 8 years of ad hoc disaster assistance propping up the farm economy, most producers we know are desperate for market prices to return to levels that will at least cover their costs of production which have exploded over the last several years. They want to move on from ad hoc assistance, in part, because there are growing concerns that much of that assistance is simply finding its way into even higher land values (or higher cash rents) or higher input costs. Further, while the One Big Beautiful Billmade a significant down payment on improving the standing farm safety net beginning with the 2025 crop year, most of that assistance will not arrive until October 2026. Even then, once that assistance arrives, it will still fall far short of the losses currently facing producers. The trade discussion has injected even more uncertainty into the markets, although the recent agreement with China has provided somewhat of a reprieve (even if it’s not yet clear how and when China will fulfill the commitments they’ve made).

While all of these issues were reaching a fever pitch earlier this fall, the government shutdown over the past 2 months sucked most of the oxygen from the room. Congress recently reached an agreement to open the government, including passing a few of the appropriations bills, but that deal did not address impending losses for the 2025 crop year or uncertainty going into the 2026 crop year.

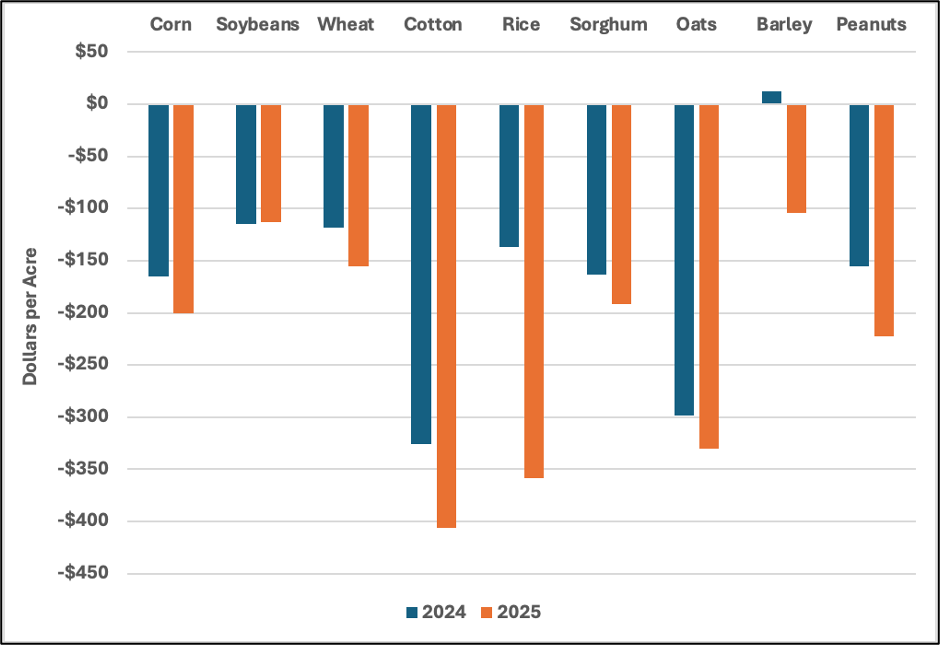

We are growing increasingly concerned that too little attention is being paid to the challenges growers continue to face. Yes, there is some talk about trade aid, but that is just one element of the challenges facing growers. Last year, Congress provided $30.78 billion for economic ($10 billion) and natural disaster ($20.78 billion) losses. As noted in Figure 1, the losses facing producers (on prices and costs of production alone) in 2025 eclipse those from 2024—yet Washington has been eerily quiet on the topic, having committed $0 at this point for 2025 losses.

In examining Figure 1, soybeans is the only crop to see an improvement in projected losses from 2024 to 2025, owing largely to the announced agreement with China and the projected $0.50 per bushel rebound in prices in USDA’s latest World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates. Even then, soybean producers are still projected to lose in excess of $100 per acre this year. In fact, all of the major commodities for which USDA reports costs of production are expected to face losses in excess of $100 per acre, with some crops like rice seeing losses double the amount of last year. And, Figure 1 is only covering losses for those crops for which USDA tracks cost of production. Other crops—for example, sugar—are also facing enormous losses. In virtually all cases, chronically low commodity prices—exacerbated by trade uncertainty—coupled with stubbornly high costs of production are the main culprits.

With news of thawing tensions on trade, the hope is that policymakers in Washington will be able to turn their attention to the huge issues facing row crop producers as they work to wrap up 2025 and prepare for the 2026 crop year. And, while growers may be growing wary of ad hoc assistance, we see little alternative in the short run. Ideally, efforts to craft a Farm Bill 2.0 will eventually make additional needed improvements to the farm safety net so we can close this nearly decade-long chapter on ad hoc assistance.

Fischer, Bart L., and Joe Outlaw. “Disaster Assistance for 2025: Is it Coming or Not?” Southern Ag Today 5(47.4). November 20, 2025. Permalink