There are many ways that crop yield can be impacted throughout the growing season, including too much rain, not enough rain, wind, hail, insect pressure, herbicide drift, and even deer. Deer damage is routinely brought up in producer meetings as a major area of concern, especially for corn, cotton, and soybean production. Crop insurance indemnities can provide data on the prevalence of this issue. Wildlife indemnity payments have been increasing in southern states, but make up less than 1.5% of total insurance indemnity payments (Duncan et al., 2023). Additionally, wildlife indemnities includes damage caused by all animals, therefore the portion of wildlife payments that can be attributed to deer is unknown. However, there can be significant losses without an insurance payment, so indemnity payments don’t show the full damage picture.

Surveys of producers typically show deer as a significantly worse problem compared to what is shown by insurance payments. Producers in Georgia reported that 19,535 acres were damaged by deer with losses of $153.85/ac (Mengak and Crosby, 2017). More broadly (Hand et al. 2024), respondents across the southeastern U.S. reported that 33-41% of cotton acres were affected by deer annually, with yield losses of 34-42%. Respondents considered deer to be the most significant pest to cotton, with damages of $152 million in 2023.

A survey was sent out to Mississippi row crop producers to determine the impact of deer[1]. Producers reported yield losses in 12 different crops, with the majority of losses coming in corn, cotton, and soybeans. In total, 13 respondents reported damage in corn, 21 reported damage in cotton, and 90 reported damage in soybeans. Respondents reported damage occurring in 45 different counties in Mississippi. Economic loss was calculated given the reported yield loss and any replant costs.

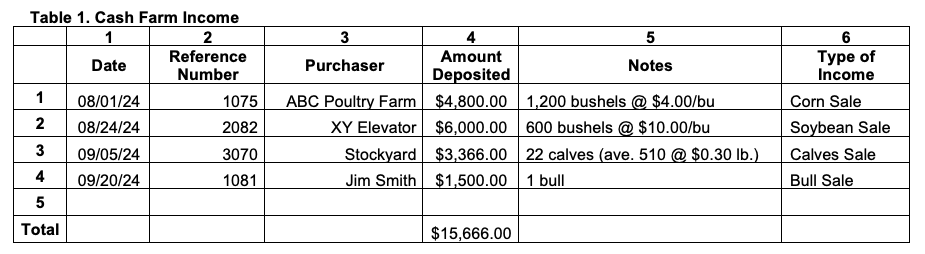

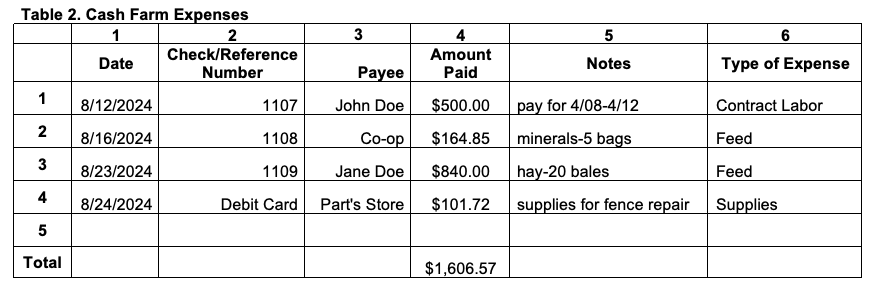

For corn, cotton, and soybeans, 17,830 total acres were reported to be affected by deer damage with a total economic impact of $4.6 million (Table 1). The acres damaged accounted for 17% of the total acres planted by the respondents. Soybeans were by far the most impacted, with 90 respondents reporting damages on 14,204 acres, of which 4,013 acres of soybeans had to be replanted. Total economic loss for soybeans was $3.68 million or $258.91/ac. Cotton had the second most acres impacted at 2,066 acres, with 597 acres being replanted. Total economic loss for cotton was $640,733 or $310.21/ac. Lastly, producers reported 1,561 acres of corn damaged with 171 acres of replant. Economic loss for corn was $294,109 or $188.46/ac.

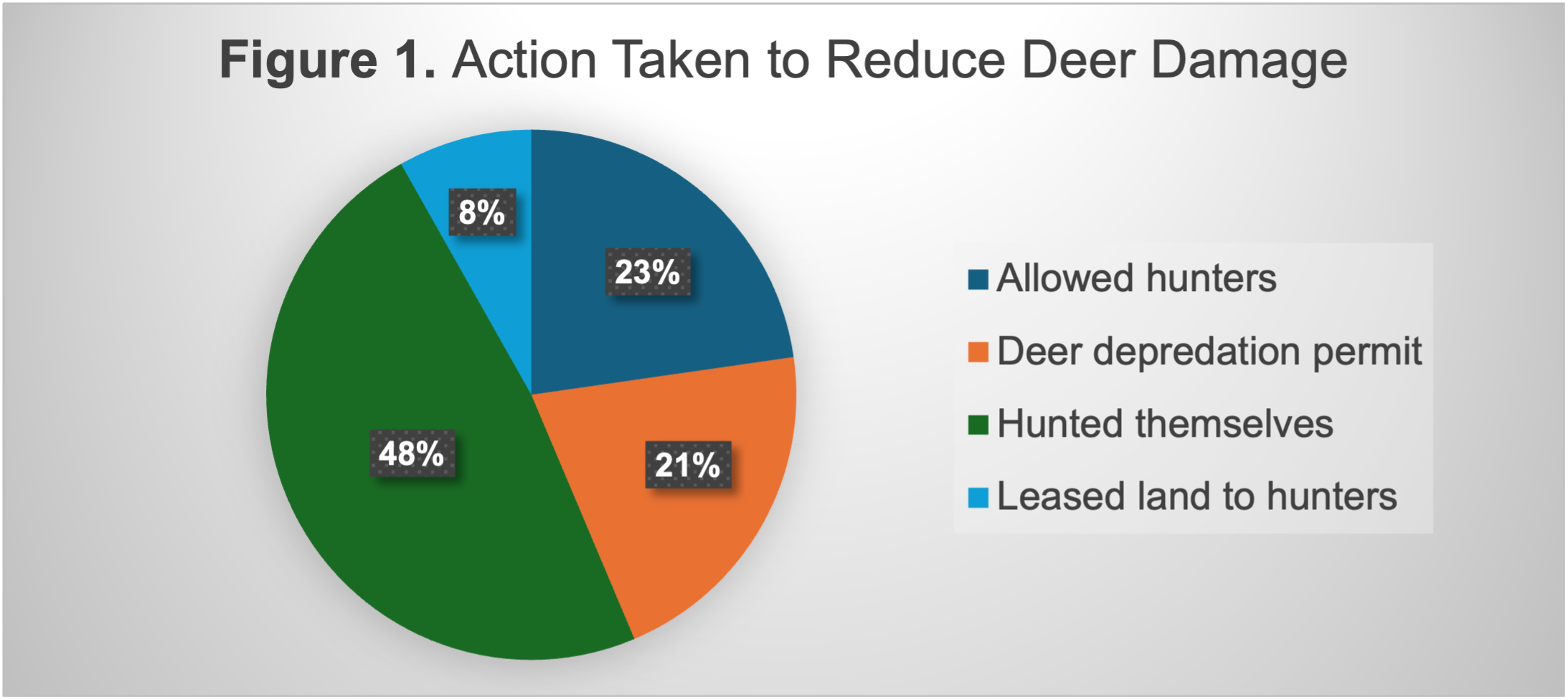

Producers were also asked a series of questions on what actions they took to reduce deer damage on their land. The most common method (48% of respondents) used hunting to control deer. This was followed by allowing other hunters on the land, 23%, and securing a deer depredation permit, 21% (Figure 1). Similar to producer surveys in other states, the results show that deer damage is a substantial issue for row crop producers. The results don’t show the full impact of deer damage, as not all producers filled out the survey. However, producers who were more severely affected by deer damage would be more likely to fill out the survey. The economic loss also depends on the year; if crop prices were higher, the economic loss would be greater and vice versa. Furthermore, there are other costs outside of yield and replant that impact producers from this issue, such as not planting the desired/most profitable crop, carcass disposal where applicable, and machinery downtime from flat tires. More work is needed in this area to determine the true impact of deer and to evaluate optimal mitigation techniques.

[1] Funding for the survey was provided by the Mississippi Soybean Promotion Board.

| Table 1. Reported Economic Loss Due to Deer Damage for Mississippi, 2024 | |||

| Item | Corn | Cotton | Soybeans |

| Respondents | 13 | 21 | 90 |

| Acres Planted | 9,222 | 9,507 | 84,243 |

| Acres Damaged | 1,561 | 2,066 | 14,204 |

| Acres Replanted | 171 | 597 | 4,013 |

| Average Yield Loss | 38 bu/ac | 416 lbs/ac | 24 bu/ac |

| Total Economic Loss | $294,109.90 | $640,732.63 | $3,677,496.10 |

| Average Loss Per Acre | $188.46 | $310.21 | $258.91 |

| Average Loss Per Respondent | $22,623.84 | $30,511.08 | $40,861.07 |

References

Duncan, H., Boyer, C., and Smith, A. (2023). Soybean Indemnity Payments for Wildlife Damage. Southern Ag Today3(29.1). July 17, 2023.

Mengak, M. and Crosby M. (2017). Farmers’ perceptions of white-tailed deer damage to row crops in 20 Georgia counties during 2016. University of Georgia Extension.

Hand, L.C., Roberts, P., and Taylor, S. (2024). Growers, consultants, and county agents perceive white-tailed deer to be the most economically impactful pest of Georgia cotton. Crop, Forage & Turfgrass Management. Volume 10, Issue 2.

Mills, Brian E., and Brianna Croft. “Deer Impact on Crop Producers: A Buck’s Buck Effect.” Southern Ag Today 5(22.1). May 26, 2025. Permalink