Contract broiler growers must make business management decisions like any other farmer. However, the scope of those decisions is very different compared to farmers growing and marketing grain, for instance. Broiler growers raising birds on contract for integrated poultry companies have contractually limited abilities to implement production management changes, and since they essentially have one “customer”, they have no chance at varying marketing strategies. Even so, some management choices may positively or negatively influence pay rates they get from the broiler company, and things that influence livability can certainly impact pounds delivered to the plant. Therefore, there may be some opportunities, like row crops or livestock farming, where a grower can choose to focus on production or pay rate improvements to potentially increase revenue. The question is whether one strategy is better than the other.

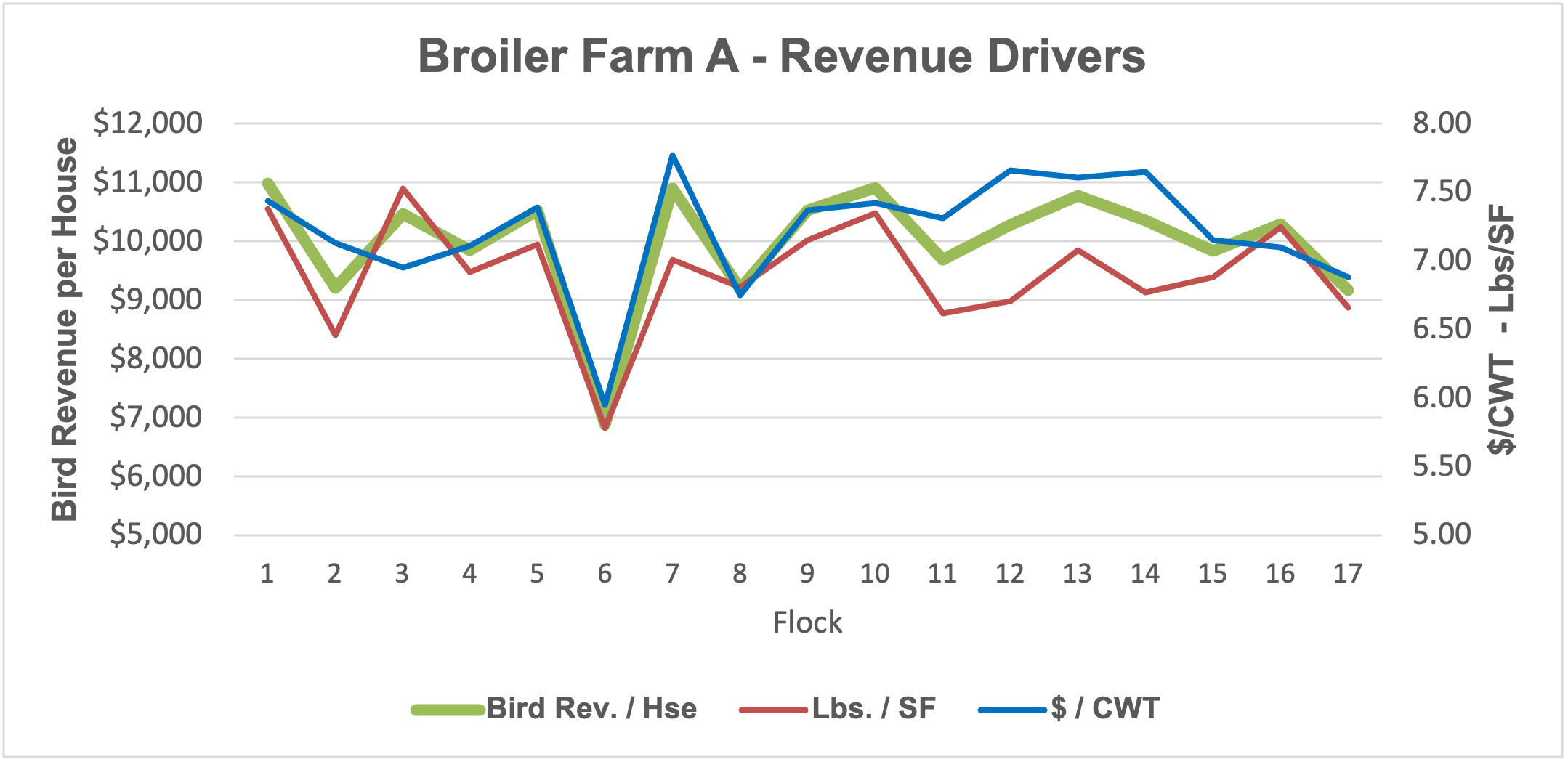

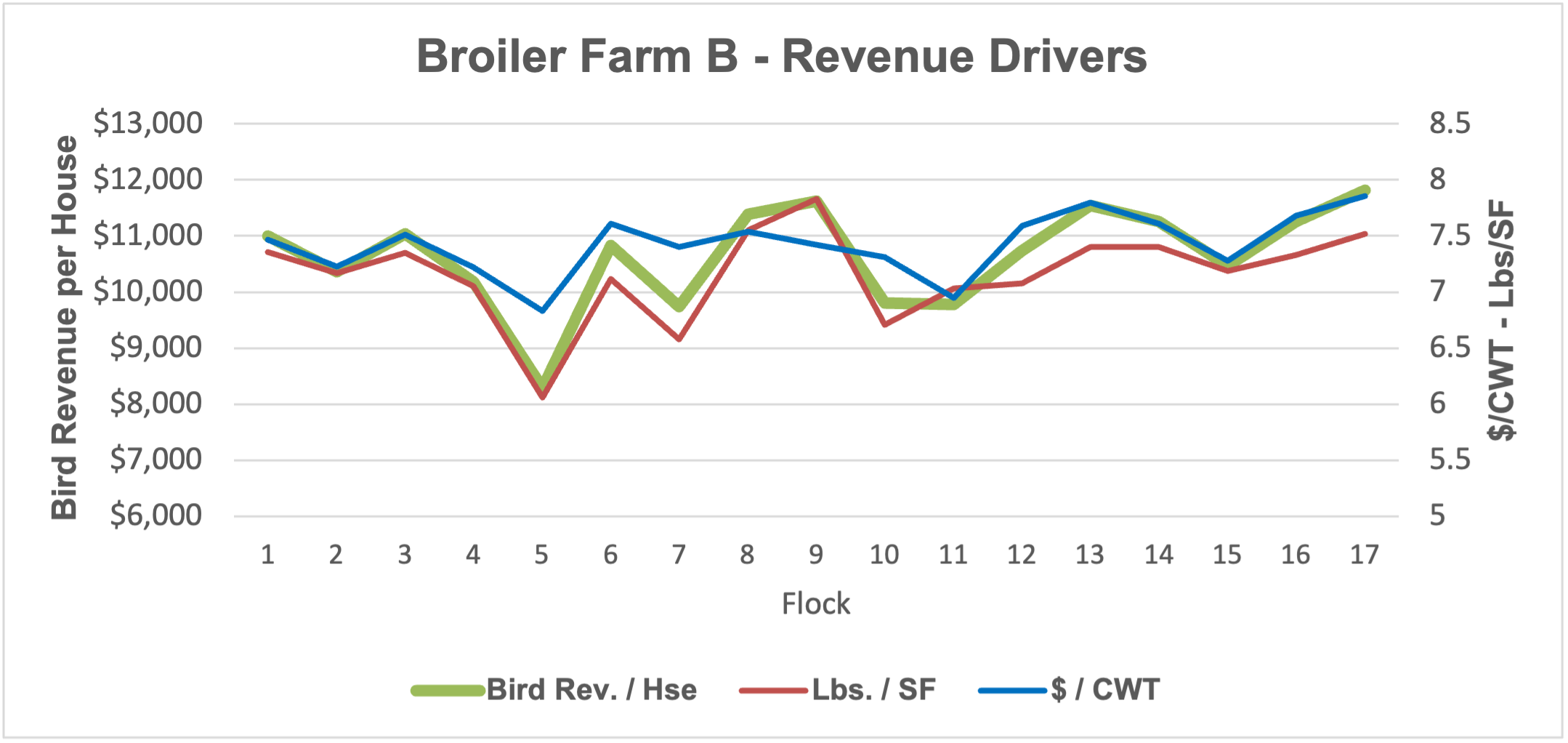

It should be reiterated that a contract broiler grower’s business operates under a simple gross revenue (GR) equation of pounds delivered to the company plant multiplied by the pay rate per pound. If we designate pounds as “L” and pay rate as “P”, the equation is simply L x P = GR. Under current typical competitive contract scenarios, a grower’s pay rate for any individual flock is a function of feed conversion ratio and corresponding flock cost compared to other farms finished and caught in the same week by the company. How well a farm’s cost compares to the average cost that week determines the pay rate. Given the limited abilities to positively impact either pounds or pay rate, the question is which might have a greater chance at positively influencing their GR? In Part 1 of our look at Broiler Revenue, we examined the variability of broiler gross revenue by looking at the two metrics of pay rate in dollars per hundred pounds delivered ($/CWT) and broiler production in pounds broken down to per square foot of housing (lbs./SF) in a nominal fashion on two similar farms across 17 flocks. From that nominal case study, we saw that although there was evidence that either could negatively or positively affect revenue, for many flocks, changes in lbs./SF seemed to override the expected effect of an increase or decrease in pay rate.

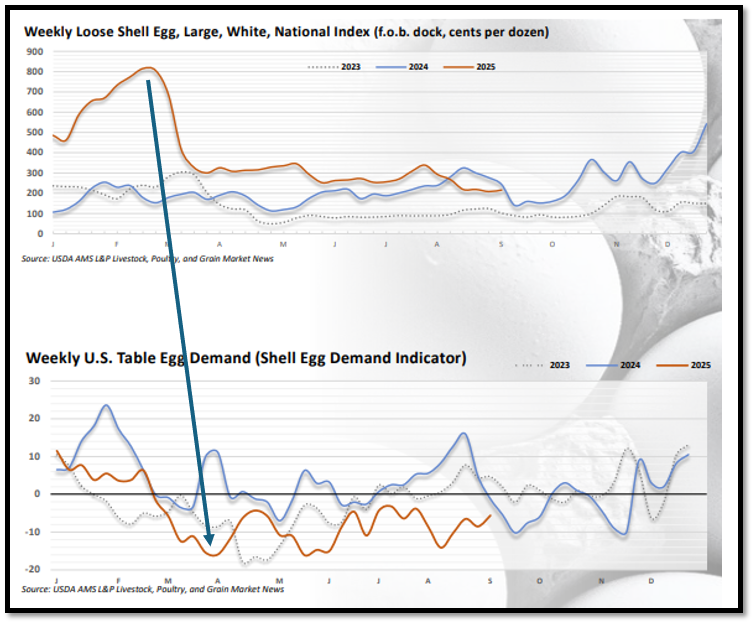

The next step looks at the same two farms and attempts to further decipher how the extent of the changes in lbs./SF and $/CWT for each flock impacts GR when compared to the farms’ own averages over the period, further trying to decide if one or the other has the most impact. By simply graphing the percent change from farm average (0%) of each of these metrics (Fig. 1a &1b), we again see what suggest lbs./SF may have a slightly more significant impact on the overall GR equation for many flocks, as often its increasing or decreasing column is the largest of the two and goes in the direction of GR. The problem is that these percentages are likely not directly comparable. In 21 of the 34 flocks, both production and pay rate moved in the same direction as the revenue line. It remains difficult to know which made the most difference to revenue because adding the % change for both does not always equate to the corresponding percentage change in revenue. In fact, it usually doesn’t. This is likely a result of the varying competitive situation that exists for every flock.

Pay rates are certainly not irrelevant, and avoiding extreme discounts is important. A close look at flock #6 for Farm A and flock #5 for Farm B is warranted. Pay rate had a significant impact on these two flocks for both farms, but Farm A got the worse end of the deal. These flocks were the lowest revenue flock for each farm, as both suffered a similar catastrophic disease outbreak (not HPAI), evidenced by the drastic decrease in production. This also resulted in significant decreases in pay rates for both as they were unable to compete positively in the tournament pay system for these flocks. However, for Farm A, the pay rate decrease was greater. This could be attributed to simple chance in the tournament pay settlement structure that week, as mentioned above. But when combined with an almost equal loss in production, the result for Farm A was 17% less revenue in dollars per house than Farm B’s bad flock ($6,879 vs. $8,283). Thus, the significantly lower pay rate cost Farm A more when combined with the lost pounds. In many cases, since there is no governmental disaster support system for such losses, the farm that suffers from such a disease outbreak receives no additional revenue support from the company either. They simply suffer the loss of birds and revenue along with the company.

Clearly, if either farm could consistently perform better in the tournament and increase their pay rate, they would generate more gross revenue, even if pounds didn’t change. However, be it for efficiency or outdated technology issues, they may be limited in their opportunity to compete for better tournament pay. In such cases, more pounds may be their only opportunity for more revenue. To examine this a little further, we can look at which improves gross revenue more for those negative revenue flocks – improving lbs./SF or increasing $/CWT. If we were to wave a magic wand over these two farms and increase the $/CWT on the negative flocks up to the farm averages, Farm A would gain $9,715, and Farm B would gain $8,514 in revenue. However, if we were to raise lbs./SF for each of those negative flocks up to farm average, Farm A would gain $11,350, and Farm B would gain $11,685. For both farms, increasing lbs./SF on poor flocks impacts revenue more, even at decreased pay rates. In the next installment, we look at what implementing changes to pay structures across the board could do to growers’ actual revenue dollars.

Figures 1 A & B: In the figures below, the 0% lines represent each farm’s average revenue, production, and pay rate across the 17 flocks. Above or below that line represents the percent change above or below farm average.

Figure 1A

Figure 1B

Brothers, Dennis. “Broiler Revenue Drivers – Part 2.” Southern Ag Today 5(52.1). December 22, 2025. Permalink