In a recent Southern Ag Today article, Anderson and Maples addressed increasing slaughter weights in beef cattle while also mentioning slaughter weights are increasing in swine and poultry. In this article, we will address poultry weights, specifically broilers.

Broiler slaughter weight has been increasing, however, the reasons for the increase are different than was outlined in the referenced beef article. The trend is a long-term situation rather than a short- or intermediate-term phenomenon. Broiler weights have been on a steady increase since the 1920s. The primary driver of these increases is market-derived; it is a slow change based on U.S. poultry consumers’ desire combined with the changing genetic potential of the birds. Unlike the beef industry, where the producers, feeders, and packers are usually separate entities, the poultry companies producing chicken own the chickens and control their genetics and production from the egg to chicken sandwich.

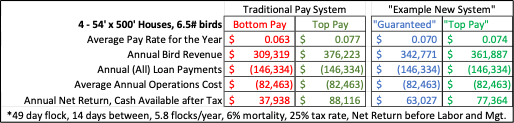

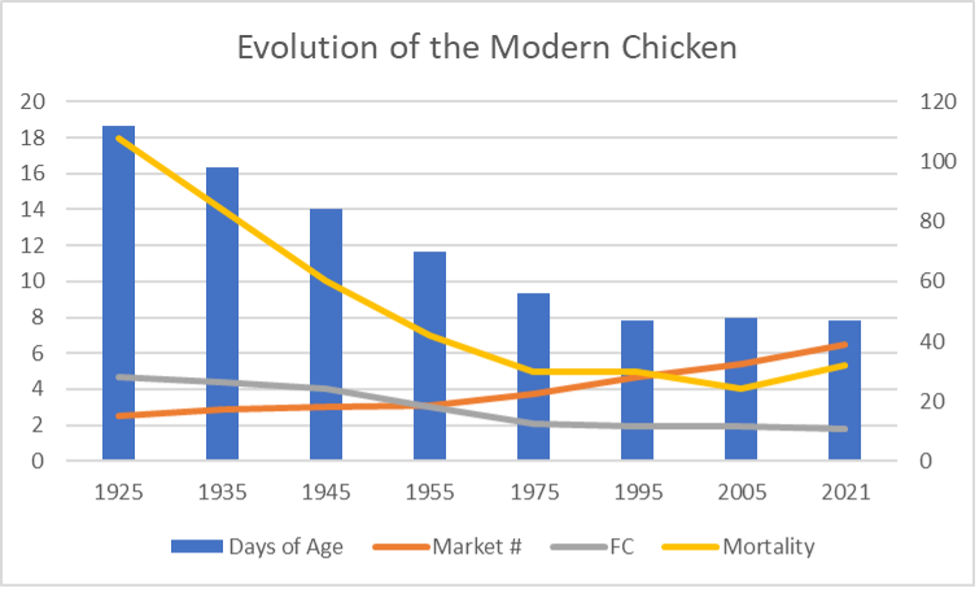

Most chickens in the U.S. are produced to meet specific market demands, and this requires varying sizes of birds. Grocery store chill-packaged products like split breasts or boneless breasts usually come from birds in the 6– 7-pound range. Fast food chicken restaurants like Popeyes or KFC typically require smaller birds to fill their “pieces” menu. These birds are usually 3.5-to-4-pound slaughter weight. The same companies sell chicken sandwiches that require filets from larger birds of upwards to 9-pound slaughter weight. Frozen processed chicken fingers and sandwich filets at the grocery store are best produced from larger birds as well. As consumers have demanded more chicken sandwiches, chicken fingers, breast filets, etc., and fewer whole birds or cut-up pieces, poultry companies have moved their genetic target toward producing birds that more efficiently meet these demands per square foot of grow-out space. Simply put, you can get more chicken fingers per square foot of grow-out space from a bigger chicken. This demand has pushed companies to produce more of the larger birds and increase the size of the larger birds (Fig 1). Since companies own the chickens and control the genetics and production, they can make these changes in response to consumer trends quickly and sustain those changes over time. From 1955 to 2021, the combined average of all broiler sizes in the U.S. increased from 3 pounds to approximately 6.5 pounds, or 116%, in response to U.S. consumer demands. But that’s not the whole story. Along with increasing weights, the poultry industry has decreased the amount of feed needed by 38 percent, from 3.0 pounds to 1.85 pounds of feed per pound of gain. The time it takes to achieve average market weight has decreased by about 20 days. Overall mortality has also decreased, though recently a change in production methods has caused a slight uptick in mortality (Fig 2). All these changes have been achieved by foundational efforts in genetics, nutritional advances, and grow-out environment/housing improvements. Overall, this represents a case study in sustainability – producing more output with fewer inputs. In commercial poultry’s case, that means more chicken for less feed, over less time, with less environmental impact.

Fig 1. Broiler weights (bird size) have increased a remarkable amount from the 1950’s to the modern bird of today. These changes have been the result of focused genetics, improved nutrition and bird environment.

Fig. 2: From 1955 to modern day, average broiler weights have increased by 116 percent. At the same time, feed conversion has improved by 38 percent. Days of age to slaughter have also decreased by 27 percent, and mortality by 21 percent.

(National Chicken Council data)

Brothers, Dennis. “Increasing Size in Broilers – A Long-Term Trend.” Southern Ag Today 5(7.2). February 11, 2025. Permalink