Commodity prices are influenced by a wide range of factors, but seasonal patterns remain an important consideration for crop marketing decisions. Even in periods of heightened volatility, understanding how prices tend to behave at different points in the marketing year can help producers evaluate timing risk and opportunity. Using soybeans as an example, this article examines historical price seasonality to illustrate how these recurring patterns can inform marketing strategies.

Seasonality reflects the tendency for prices to follow recurring patterns throughout the marketing year, largely driven by changes in supply availability. Across crops, prices are often weakest near harvest, when supplies are most abundant, and strengthen later in the year as stocks are drawn down. While this pattern is widely understood, it is not universal. In some years, crop prices are stronger at harvest than during the remainder of the marketing year; however, these “harvest-strong” years are relatively rare and tend to behave differently than the typical seasonal pattern.

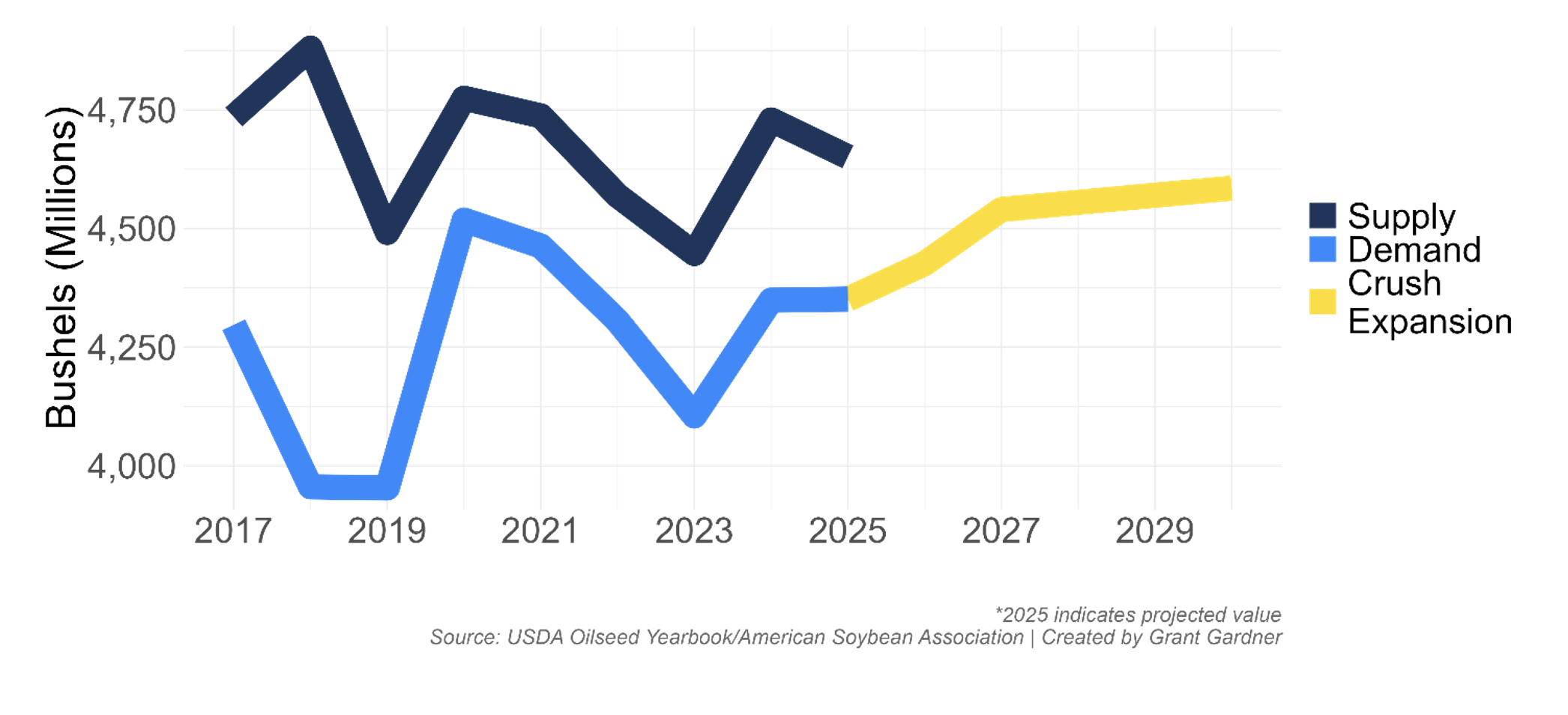

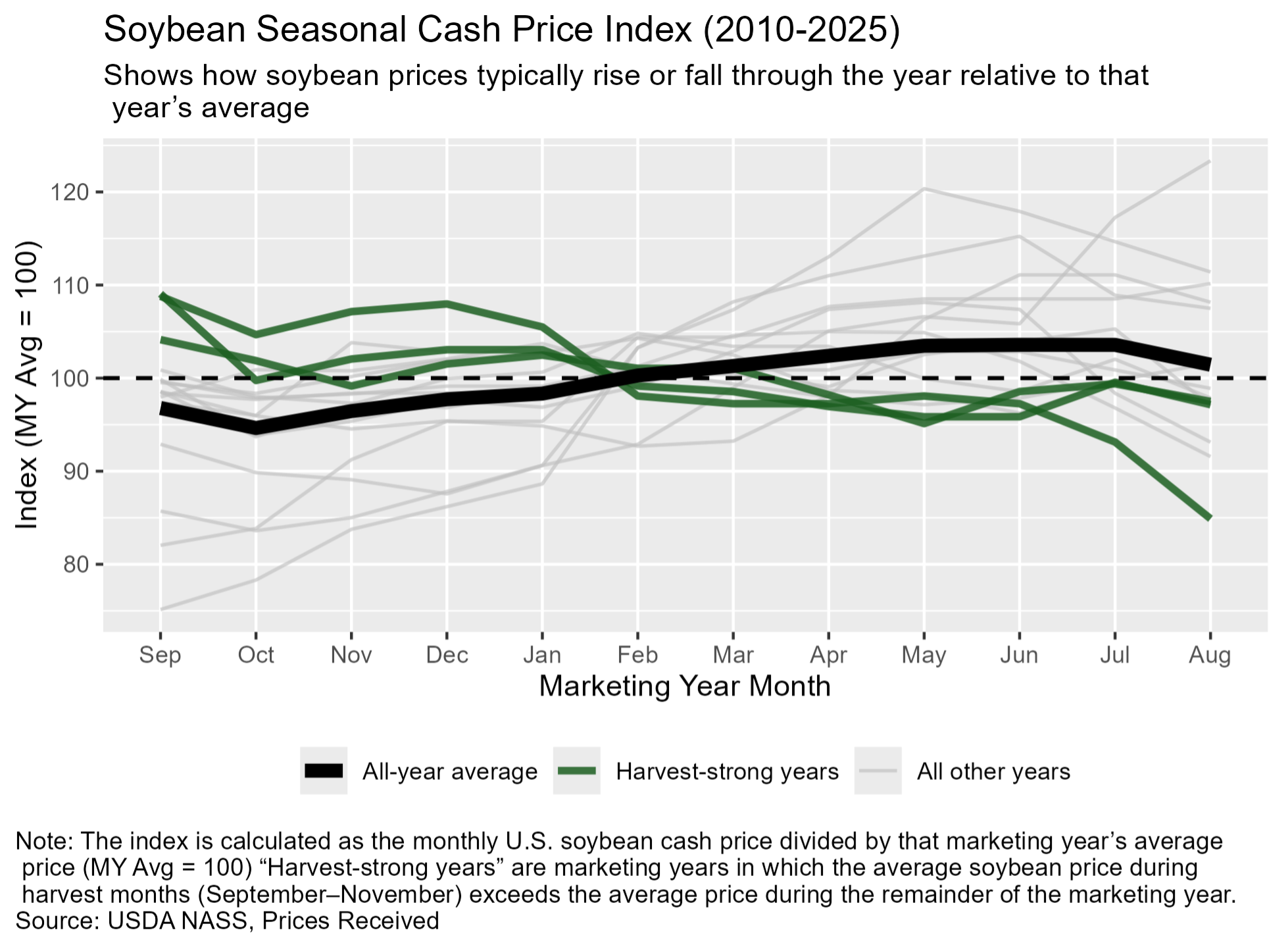

Figure 1 illustrates soybean cash price seasonality using national monthly prices from 2010–2025. Prices are expressed as an index, calculated by dividing each month’s price by that marketing year’s average price. A value of 100 represents the average price for the year, while values above (below) 100 indicate prices that were higher (lower) than average.

The thick black line in Figure 1 shows the average seasonal pattern across all years. This long-run average confirms a familiar story: soybean prices tend to be relatively weaker in the early fall, strengthen through winter and spring, and often peak in late spring or early summer before declining as new-crop supplies approach. From a seasonal perspective, this pattern suggests that pre-harvest and late-spring marketing opportunities often outperform harvest-time sales.

Not all years follow this average path. The green lines in Figure 1 highlight harvest-strong years—marketing years in which average soybean prices during harvest (September–November) were higher than prices during the remainder of the marketing year. The lighter gray lines represent all other years. Over the past 15 years, soybean prices were higher at harvest in only three years: 2015, 2019, and 2024. In 2015, harvest prices were supported by weather risk and relatively tight global balance sheets. In 2019, prices were influenced by trade uncertainty and a delayed supply response. Most recently, in 2024, tight stocks and global supply concerns helped support prices at harvest. In contrast, the remaining years exhibit stronger pricing opportunities outside the harvest window.

This distinction has practical marketing implications. In most years, weak harvest prices are followed by some degree of seasonal recovery, making post-harvest marketing opportunities more attractive. When prices are unusually strong at harvest, however, the historical record suggests that price upside later in the marketing year may be more limited.

The key takeaway is not that producers should market at the same time every year, but that seasonality provides a useful baseline expectation. When prices align with typical seasonal patterns, historical averages can help frame marketing decisions. When prices deviate, particularly when harvest prices are strong, it may signal that capturing favorable prices sooner deserves consideration. Incorporating seasonal patterns alongside market fundamentals, risk tolerance, and cash-flow needs can help producers make more disciplined and informed soybean marketing decisions.

Figure 1.

Gardner, Grant. “Price Seasonality: What the Pattern Shows.” Southern Ag Today 6(6.3). February 4, 2026. Permalink