The November 2025 WASDE report is the first since September to be released due to the government shutdown taking place from October 1, 2025, to November 12, 2025. This month’s report was a relatively quiet one with few significant changes to the balance sheets for southern crops. Season-average farm prices for corn and soybeans were revised upward from the September report, while the prices for rice and cotton were revised downward. Despite the increases in corn and soybeans, futures markets responded with sharp declines in the nearby futures contracts. This was likely driven by production being higher than industry expectations for corn and soybean exports falling short of expectations. We provide a detailed breakdown of the changes to each crop’s respective balance sheet below.

Long-Grain Rice:

This month’s 2025/26 outlook for U.S. long-grain rice includes lower supplies, unchanged domestic use and exports, and decreased ending stocks. Long-grain production was reduced by 1 million hundredweight (cwt.) this month to 152.7 million. Yields were lowered in all Midsouth states, with Louisiana, Mississippi, and Missouri all seeing average yields reduced by 100 pounds per acre this month. Arkansas’ average yield was lowered by 50 pounds per acre. With no adjustments to demand, long-grain ending stocks were lowered by 1.1 million to 36 million cwt., down 3.5 percent from last year. The 2025/26 season-average farm price (SAFP) was lowered by 23 cents per bushel this month to $5.18 per bushel—the lowest since 2018. This further increases the outlook for sizeable 2025/26 PLC payments, with the current projected payment rate for long-grain at $2.44 per bushel—up 23 cents from September.

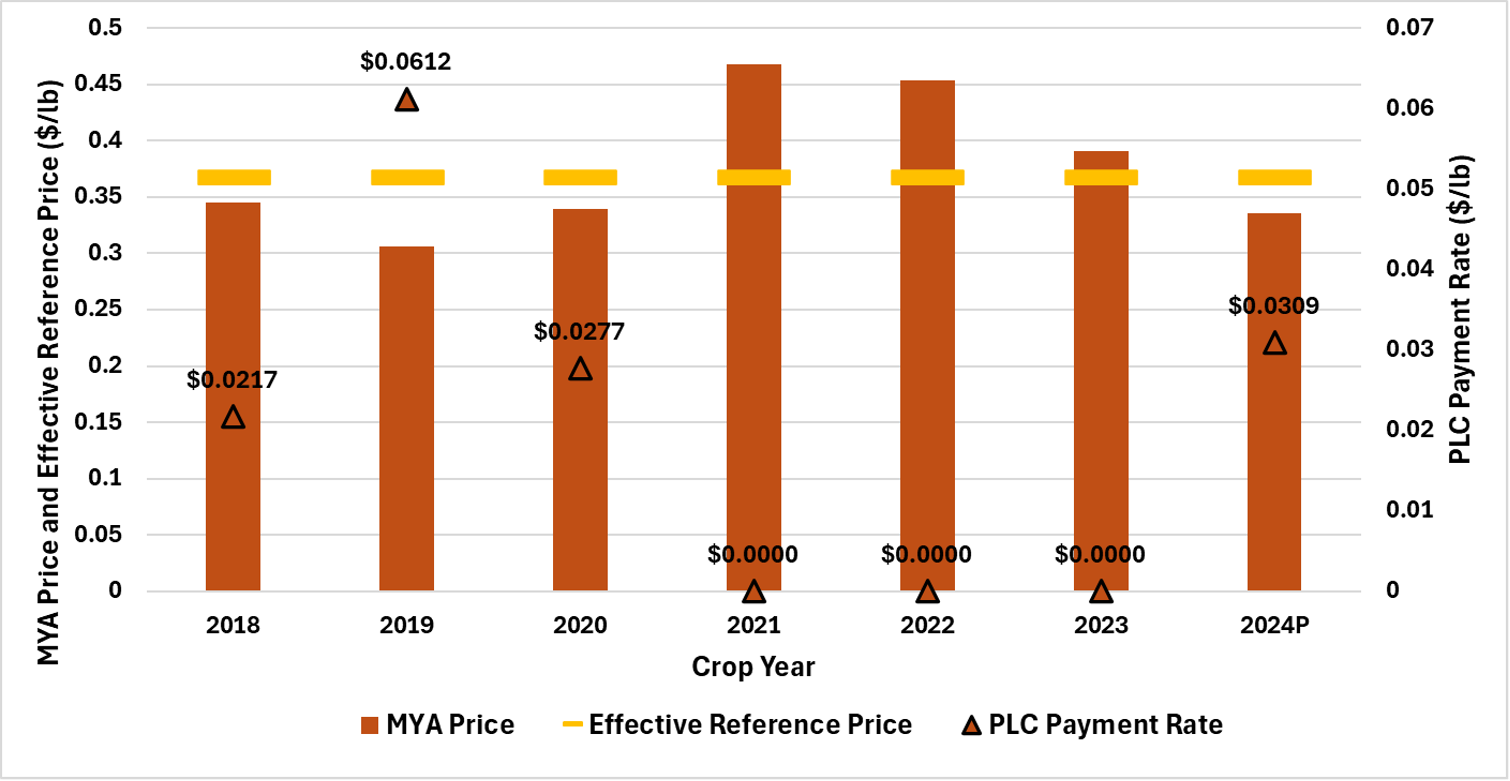

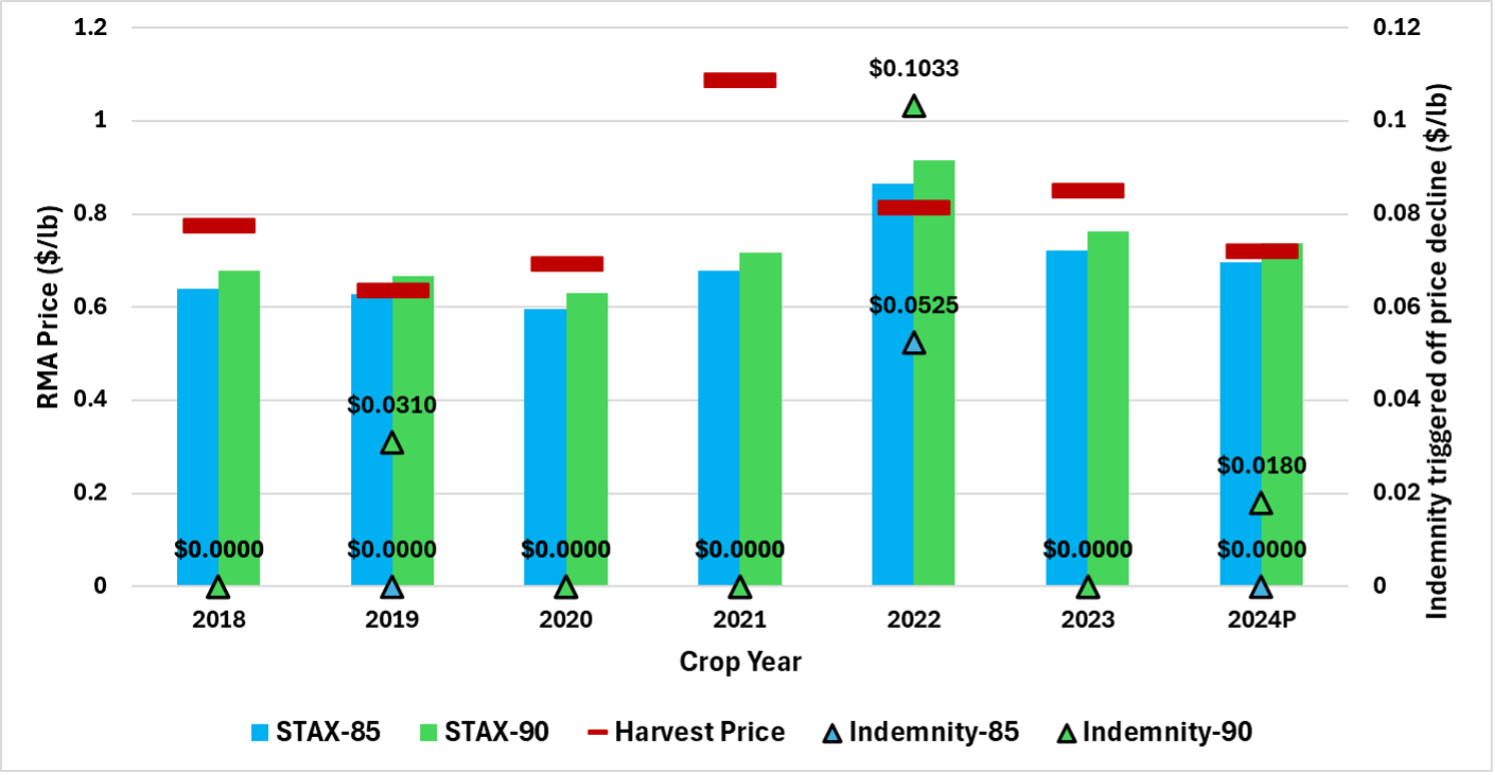

Cotton:

The November outlook for 2025/26 U.S. cotton supply and demand included higher production, exports, and ending stocks compared to September. There were no changes to domestic mill use and imports. USDA projected the 2025/26 U.S. crop to reach 14.12 million bales, up roughly 897,000 bales from the September report. The national average yield per acre increased by 58 pounds this month to 919 pounds. This would be the second-highest yield on record, behind 2022’s 953 pounds.

U.S. exports were raised 200,000 bales to 12.2 million bales while mill use was unchanged from September at 1.70 million bales. This generates a total 2025/26 offtake of 13.90 million bales. Ending stocks for 2025/26 are projected at 4.30 million bales for an ending stocks-to-use ratio of 30.9%. This month’s projected average farm price for 2025/26 is 62.00 cents/lb, down 2 cents/lb from September.

Corn:

The November report for 2025/26 U.S. corn showed an increase in total supply, exports, and carryover. Production was revised downward 62 million bushels from 16.814 to 16.752 billion bushels based on a reduction of 0.7 bushels per acre in the national yield. On the demand side of the balance sheet, total use is increased 100 million bushels based on an increase in exports of the same amount. Beginning stocks were increased by 207 million bushels from 1.325 to 1.532 billion bushels. Taken together, these changes represent an increase in total supply of 144 million bushels, which is larger than the 44 million bushel increase in total use. Interestingly, this results in a 10-cent increase in the 2025/26 projected season-average price to $4.00/bushel, likely driven by the reduction in national yield and a record large export forecast of 3.075 billion bushels.

Soybeans:

The November report for 2025/26 U.S. soybeans showed decreases across the board. Production was revised downward 48 million bushels from 4.301 to 4.253 billion bushels based on a reduction of 0.5 bushels per acre in the national yield. On the demand side of the balance sheet, total use decreased by 51 million bushels based on a decrease in exports of the same amount, driven by lower domestic supplies and increased exports by Brazil and Argentina. While a trade deal between the U.S. and China has been announced, which guarantees soybean purchases through 2028, the announcement also increased the price of U.S. soybeans by 90 cents since October 30th, making the relative price of soybeans lower for Brazil. Beginning stocks decreased by 14 million bushels from 330 to 316 million bushels. Taken together, these changes represent a decrease in total supply of 61 million bushels, which is larger than the 51 million bushel decrease in total use. This 10-million-bushel net reduction in ending stocks results in a 50-cent increase in the 2025/26 projected season-average price to $10.50/bushel.

Thoughts on USDA’s November Reporting

Ahead of USDA’s November WASDE and Crop Production reports, concerns arose that NASS might not have sufficient time to conduct an adequate survey of fields and producers, given the recent government shutdown. The November 2025 Crop Production survey had 6,692 participants compared to 5,838 last year. Regarding the field surveys, NASS enumerators visited the fields in October and early November, despite the shutdown. NASS provided the objective corn and soy yield data for November. One might argue there is no reason to believe that the November yield estimates are any less (or more) reliable than in previous years.

However, USDA did note “some U.S. data sources that are typically used were not available for the November 2025 WASDE.” Further noting, USDA mentioned changes to the U.S. balance sheets reflected all U.S. government data available at the time of publication. Over the past month, information such as the weekly Export Sales and daily export “flash” reporting was unavailable, as well as government reporting on ethanol production and consumption.

The next WASDE is scheduled for December 9th. USDA normally makes no crop production adjustments until the NASS Crop Production Annual Summary is released in January. In the near term, the major crop markets will be focused on actual Chinese demand for US soybeans and cotton as well as South American weather. These will be primary drivers of price discovery for the balance of 2025.

Biram, Hunter D., and H. Scott Stiles. “November 2025 WASDE Report is Relatively Quiet Despite Surprises in Production and Exports.” Southern Ag Today 5(47.3). November 19, 2025. Permalink