From October 1, 2025, to November 12, 2025, the U.S. federal government was largely shut down until a congressional stalemate was resolved involving appropriations legislation. The 43-day duration of this shutdown was unprecedented, but some of its effects are taking even longer to resolve.

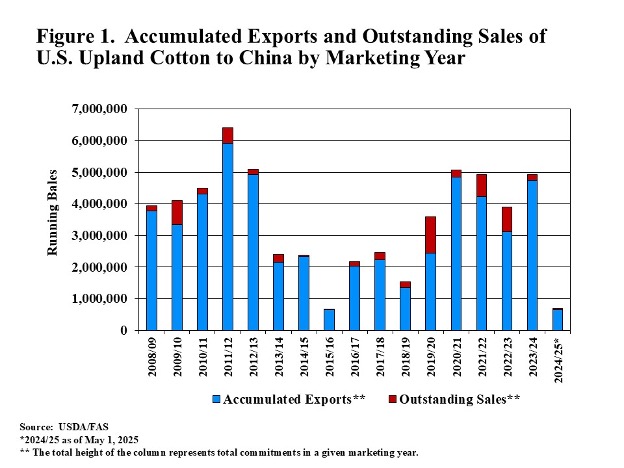

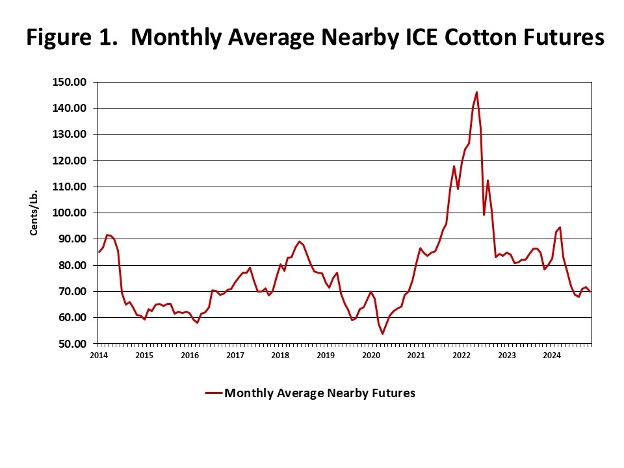

The agricultural marketing implications of the federal shutdown included the suspension of important public agricultural data, especially near term (i.e., weekly) data. Such data are important for characterizing near term influences on cotton prices. For example, the USDA Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) publishes a weekly export sales report for cotton (and other row crops) which serves as a useful indicator of export demand. As displayed in Figure 1, cotton weekly export sales in relation to nearby ICE cotton futures are helpful in explaining or predicting export quantities demanded.

USDA FAS weekly export sales reports resumed on November 13, but export data picked up where it left off (i.e., for September 18). Even with issuing semi-weekly reports to catch up, the normal one-week lag schedule won’t be achieved until January 8, 2026. The one-week lag schedule has the most value as a current demand indicator. But instead of a 43-day delay, we are really dealing with a 112-day delay (September 18 to January 8) until a full return to normal reporting. Thus for over a hundred days, the only market participants with knowledge of the current export demand picture were the merchandizers.

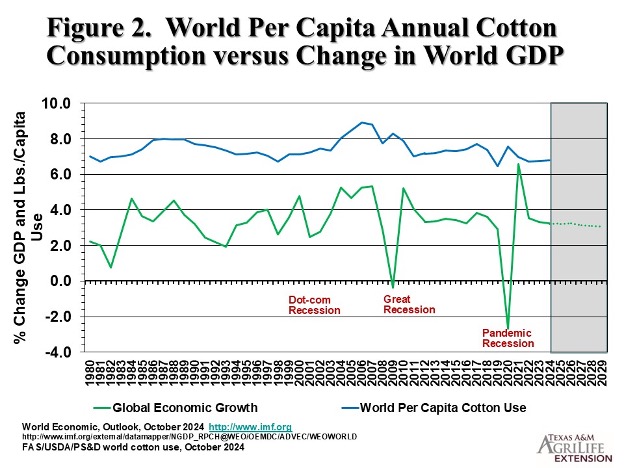

For another example, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) publishes weekly “Commitment of Traders” (COT) data on the positions of index funds and hedge funds in agricultural futures markets (Figure 2). The changes in these speculative futures positions have near term value in explaining fluctuations in ICE cotton futures. Like the cotton export sales data, the COT data have little explanatory power outside of a week old.

The 2025 Commitment of Traders (COT) report schedule saw significant revisions due to the federal funding lapse, leading to catch-up publications throughout the end of 2025. Reports for late October and November 2025 were pushed to December 2025, with the CFTC increasing frequency until a return to the normal reporting schedule on December 29, 2025. Beyond the direct shutdown (7 to 8 weeks) the CFTC near term publication schedule won’t be fully restored until after a 17-week period.

Thus, the disruption of valuable near-term cotton marketing data flow has been quite long, but as we enter the new year, we are finally back to a normal reporting period.

Robinson, John. “An End to the Disruption of Two Key Weekly Federal Crop Reports.” Southern Ag Today 5(53.3). December 31, 2025. Permalink