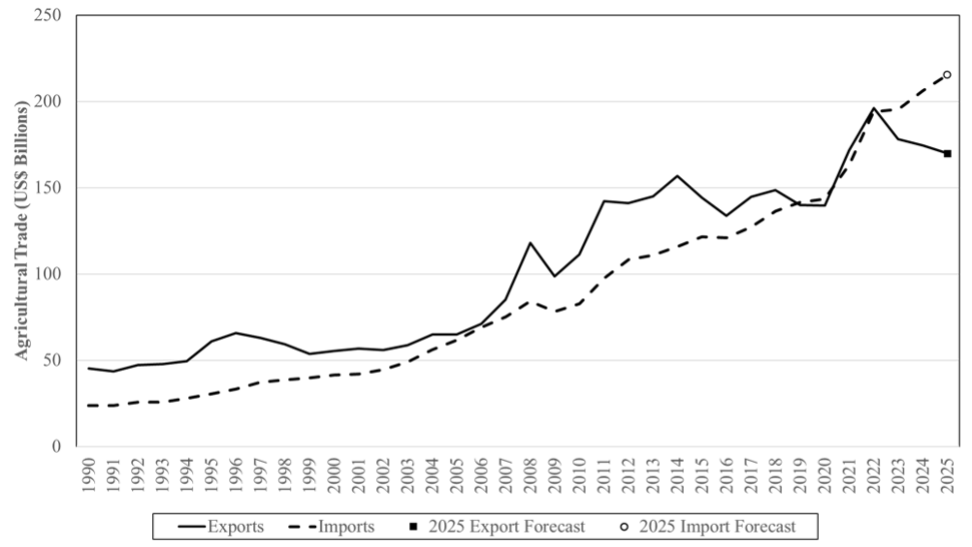

The U.S. agricultural trade outlook for 2025 is clouded with uncertainty driven by both global economic dynamics and domestic policy shifts. As shown in Figure 1 below, the USDA projects that agricultural exports could reach $170 billion—a slight decrease from the 2024 calendar year. Imports are expected to reach a record $215.5 billion. If both projections are accurate, these trade patterns would result in a record $45.5 billion agricultural trade deficit.

Figure 1: USDA Outlook for Agricultural Trade

However, prospective changes in domestic trade policy loom large over these projections. The incoming Trump administration has signaled plans for sweeping tariffs, including a proposed 60% tariff on Chinese goods and a 10% tariff on all other imports. These measures aim to protect domestic industries, but they risk triggering retaliatory tariffs from key trade partners. A resurgent trade war could severely restrict access to critical export markets, particularly China, the largest buyer of U.S. soybeans prior to the previous trade war. Retaliatory actions could further depress already struggling commodity prices and deepen challenges for U.S. farmers.

The USDA’s outlook underscores that exports to traditional markets such as Mexico and Canada are forecasted to remain strong, driven by demand for corn, beef, and dairy. However, exports to China are expected to decline further, exacerbated by weakened soybean demand and competition from Brazilian suppliers. At the same time, the anticipated tariffs could raise costs for imported agricultural inputs, further squeezing U.S. producers.

The broader economic context offers mixed signals. Easing inflation and steady global GDP growth may support international demand for U.S. agricultural products. However, a strong dollar continues to challenge U.S. export competitiveness, particularly as other nations’ currencies depreciate. Another main contributor to the loss of competitiveness of U.S. agricultural products in the international arena is the increase of cost of production in recent years. In 2018, U.S. farmers spent a total of $354 billion on inputs, however, by 2023 farmers spent $481.9 billion, an increase of 36 percent.

The long-term impact of the Trump administration’s trade policies remains to be seen, but the path forward will require balancing protectionist strategies with the need to maintain and grow critical trade relationships to support the agricultural sector.

Schaefer, K. Aleks, and Luis Ribera. “2025 U.S. Agricultural Trade Outlook: Navigating Uncertainty Amid Policy Shifts.” Southern Ag Today 5(2.4). January 9, 2025. Permalink