USDA released its Cattle inventory report on Friday, January 31st. This report is the benchmark for data on the number of total cattle in the U.S. and estimates of beef and dairy cows, replacement heifers, and stockers on small grain pastures. The data is the starting point for estimates of beef production and prices in the future.

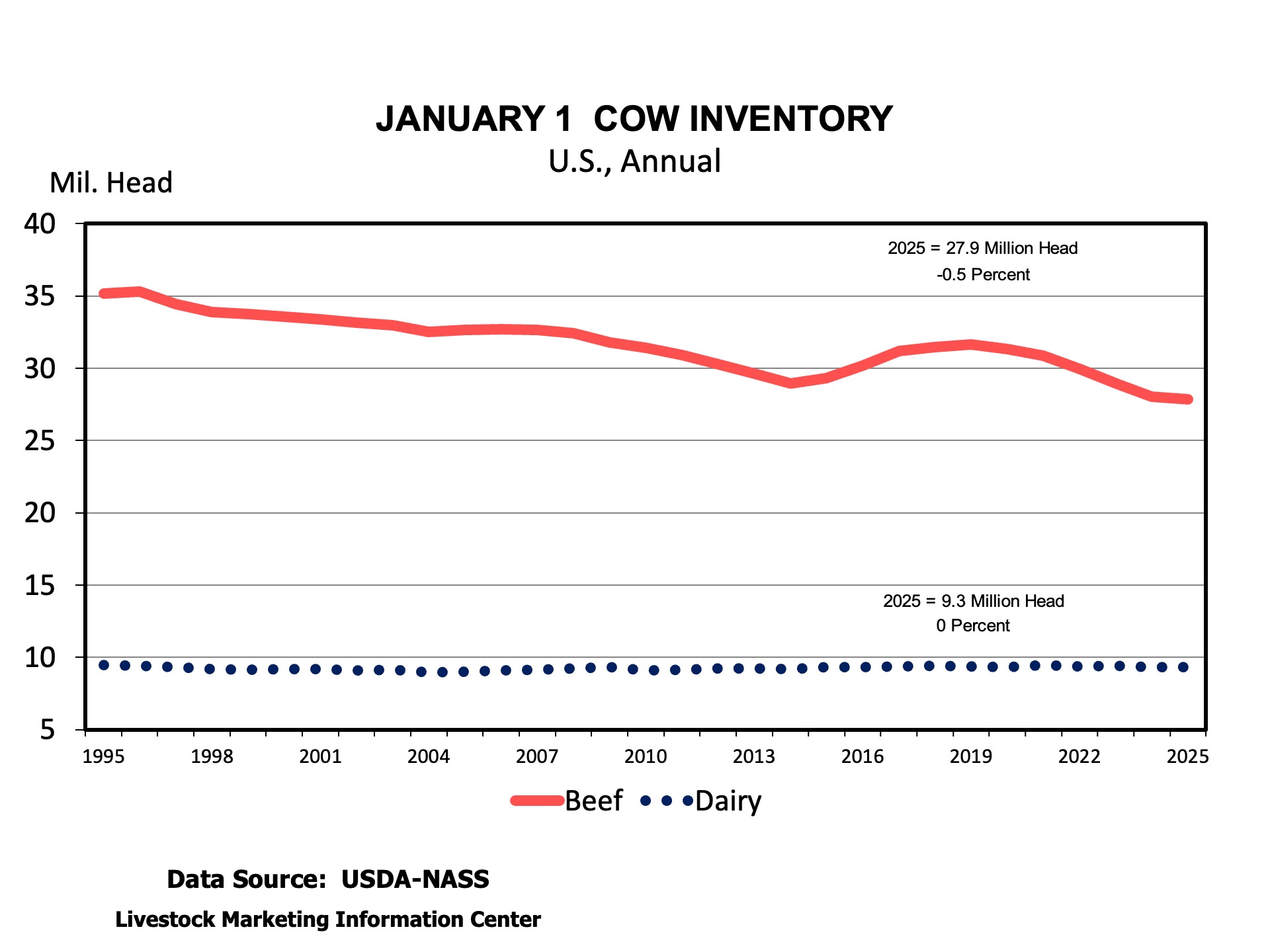

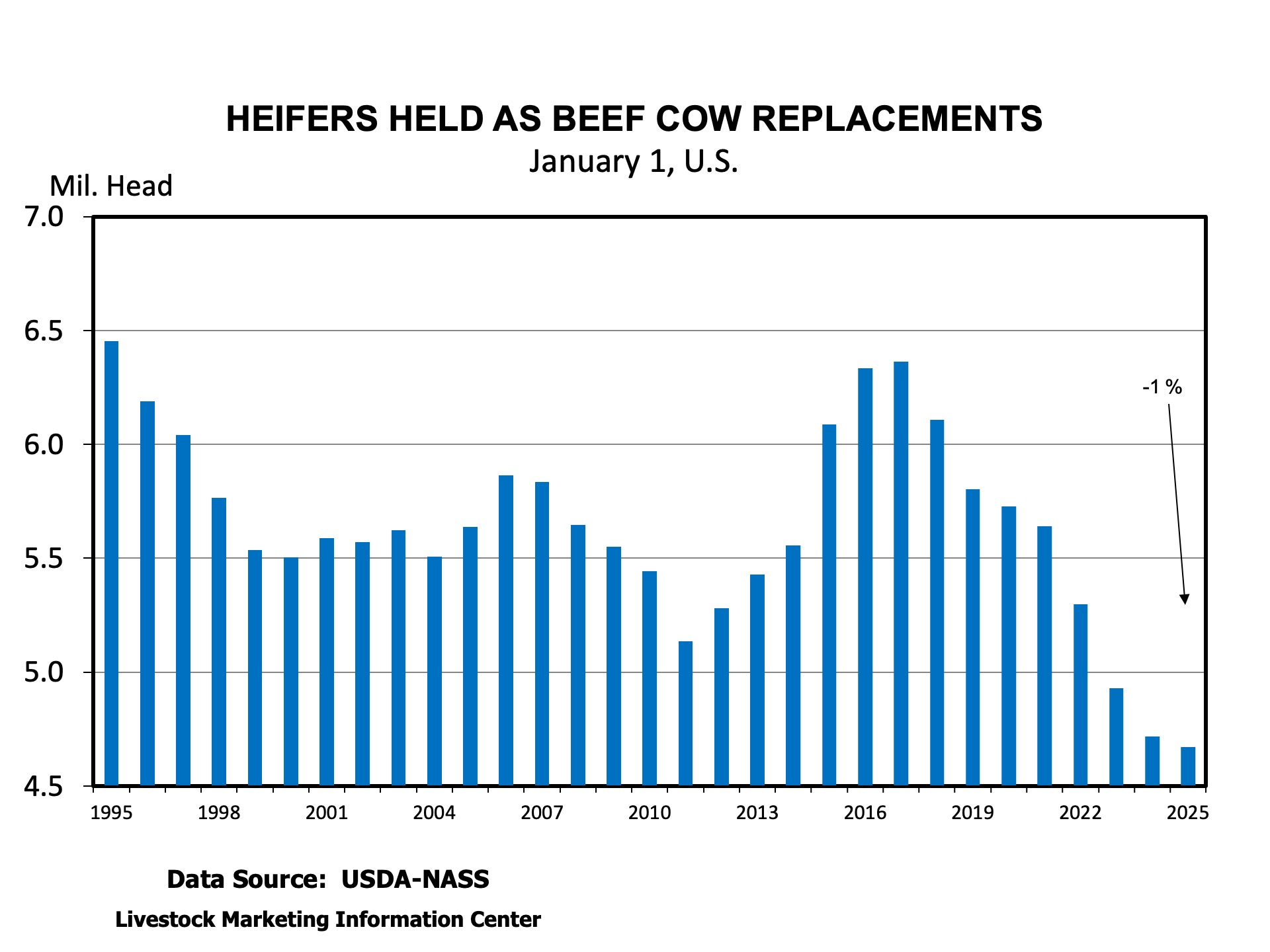

The big numbers in the report included a January 1, 2025, total cattle inventory of 86.66 million head, down 1 percent from the year before and the fewest since 1951. Beef cows were down 0.6 percent to 27.86 million head the fewest since 1961. Heifers for beef cow replacement were down 1 percent to 4.67 million, the fewest since 1949.

One of the interesting components of these statistical reports are revisions. USDA gathers the surveys and other information from other surveys and data reports and revises the previous year’s data if warranted. Sometimes revisions are important and sometimes they are a non-event. This report had some revisions that are interesting. Some states were not reported beginning in this survey due to budget cuts. While producers were surveyed, their numbers were only included in the total U.S. statistics.

Today’s article includes comments from SAT livestock economist writers to offer a few thoughts on their state and the report across the South.

Matt Fischer, Clemson University:

South Carolina cattle and calves inventory expanded in 2025 from 2024. Total cattle calves inventory on January 31, 2025, was reported 295,000, up 2% from 2024. Cow inventory increased in 2025 by 1%, from 156,000 to 157,000. Unfortunately, USDA did not provide inventory on any other category. Leaving speculation where the missing 4,000 head would be categorized, hopefully in unreported heifer inventory. Regardless, South Carolina reported inventory expansion in 2023 only to follow liquidation trend in 2024.

Will Secor, University of Georgia:

Broadly, the report was in-line with expectations. Georgia’s total cattle inventory and its inventory of beef cows declined by about 2% in 2025 compared to 2024. This confirms that there was no herd rebuilding in Georgia last year. However, these declines are smaller compared to last year despite dry weather struggles throughout much of the year. Additionally, the number of beef cow replacement heifers held steady at 85 thousand head.

Hannah Baker, University of Florida:

In Florida, the total number of cattle and calves was unchanged at 1.56 million head. The number of beef cows that calved in 2024 slightly increased by 0.3% (3,000 head) to 865,000 head. Florida is now ranked 10th in beef cattle production (9th last year). Florida’s 2024 calf crop was 1% larger than 2023’s at 770,000 head. The number of beef cow replacements remained unchanged at 115,000 head, unlike last year when we saw a 4% decline. While we don’t see major signs of expansion, we do see signs of stabilization starting in the Florida beef cow herd.

Kenny Burdine, University of Kentucky:

The overall decrease in beef cow numbers was not a surprise. But cow slaughter really pulled back in late 2024 and I do think the decrease in beef cow numbers was smaller than what many expected in the first half of 2024. The 200,000 cow downward revision to 2024 beef cow numbers is also worth noting. My general take on beef cow numbers is that liquidation is slowing, but that is primarily due to reduced culling.

Beef heifer retention was down by about 1% (also after a downward revision to last year), which was largely expected given the number of heifers on feed. The main point here is that we are still not currently retaining enough heifers to grow the beef herd given a reasonable assumption of cow slaughter in 2025.

If weather allows, I think it is very possible that we see more heifer retention during 2025. It’s also good to remind ourselves that the January 1 report is a snapshot of inventory. There are additional heifers in growing programs (grazing, backgrounding, etc.) that could also potentially be bred this year if market and weather conditions remain favorable. And the inverse is also true – not all of those heifers being held for replacement purposes will end up entering the cow herd.

I don’t know what to make of the decrease in cattle grazing small grains. The calf crop was smaller last year, wheat grazing prospects were late to develop, and I also think a lot of calves moved early because it was dry for much of late summer-early fall.

NASS estimated our beef cow herd to be down by 38,000 head. This was consistent with what our county Extension agents had been telling me. Land constraints are real in the Commonwealth. We have lost a lot of pasture ground to row crop and development pressures. High land prices do tend to negatively impact cow numbers, especially for young and beginning farmers. I did not expect to see the increase in the estimated number of heifers held for beef replacements. But there was also an estimated increase in the heavy (> 500 lbs) steer and bull categories. I think this speaks to a gradual shift away from cows and towards growing operations in Kentucky.

Andrew Griffith, University of Tennessee:

I expected a larger decline in the beef cow herd and beef heifers held for replacement given the quantity of heifers that went on feed and the fact that cow slaughter was still a large number. Beef cow slaughter was certainly much lower in 2024 than in 2023, but beef cow slaughter in 2023 was extremely large. Thus, this was a little surprising to me. As far as state of Tennessee, I was surprised that the beef cow herd declined by 9,000 head while the number of heifers remained the same. Somehow, we maintained the same calf crop compared to last year despite having fewer cows. I do have some concerns about the survey response rate over time.

Josh Maples, Mississippi State University:

Total cattle inventory in Mississippi was unchanged at 810,000 head. The calf crop was also reported unchanged at 345,000 head. I was a little surprised the calf crop was not lower in Mississippi. The big adjustment this year was the change in data reported. Mississippi is one of the 19 states that were dropped (due to USDA-NASS budget cuts) from individual state reporting for important categories such as beef cows, replacements, etc. Producers were still surveyed, but their responses were aggregated into the total cattle number presented.

David Anderson, Texas A&M University:The beef cow herd increased about 60,000 head or 1.5% from January 1, 2024. But, this larger cow herd is the result of a downward revision to last year’s cow herd. I often think it is helpful to look at the data over a longer period and doing so shows that the herd is smaller than 2 years ago. So, I don’t think the report is too surprising thinking about it in that context. Fewer replacement heifers were retained according to the responses. The 4.075 million beef cows reported are the fewest since 1959 except for the 3.9 million in 2014 following the drought of 2010-2013.