The recent H.R. 1 budget reconciliation bill signed into law on July 3, 2025 made a number of changes to farm programs and qualifications that would normally be addressed in a five year farm bill. One of these is payment limitations on federal programs (e.g. conservation, crop insurance subsidies, disaster payments, etc.) imposed on farms organized as S corporations (S corps) or limited liability companies (LLCs). The need for this change was highlighted in a previous Southern Ag Today article that called attention to the disparate treatment of certain entities. As noted in the article, modern-day payment limitations trace their origins to the 1970 Farm Bill.. Since that time, larger farms – those with multiple owners actively engaged in operations – often have required specialized structuring to allow their operating or landholding entity to capture more than one payment limitation to contribute to the overall operation.

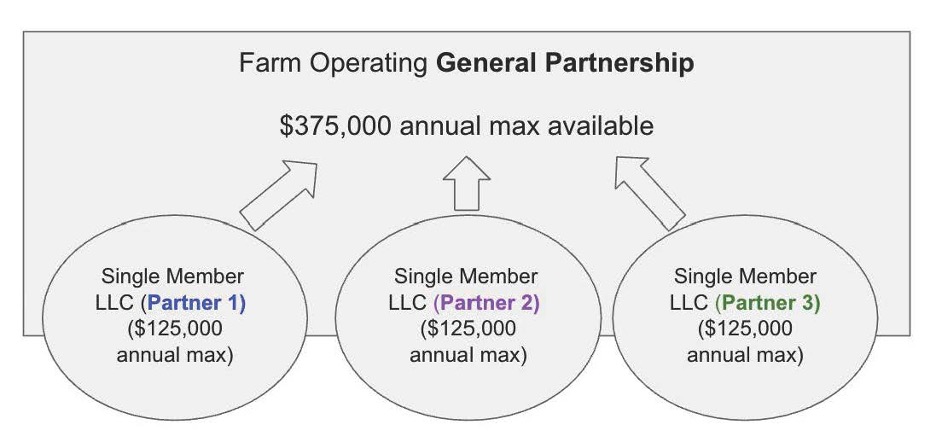

Since the 2008 Farm Bill, LLCs and S corps have been treated as “individuals” and limited to one payment limit, regardless of the number of members or shareholders in the entity. This was the case even though for federal income tax purposes, these entities are considered “pass through” entities where the individual equity owners pay or take their pro-rata share of tax liability (or loss). Partnerships and joint ventures on the other hand were explicitly exempt from the payment limit, so each partner could receive payments up to their individual limitation and apply to the business of the partnership or joint venture (i.e. the farm operation). One distinction is that such arrangements are not considered entities in that they do not require registration and formation under state law. As such, partnership arrangements are not considered legal individuals, and they do not shield the equity owners from individual liability for actions of the partnership or other partners.Such lack of liability protection made operating as a partnership risky to the individual partners, perhaps not worth the risk simply to attain multiple payment limitations. A workaround legal arrangement came into practice, whereby the farm firm would operate as a partnership, but the individual partners would organize single member limited liability companies or S corps and assign their interest to their LLC or corporation, such that the LLC or corporation became the partner, rather than them in their personal capacity. This had the theoretical effect of shielding their personal assets from any tort litigation liabilities of the partnership. The arrangement looked like this:

In this arrangement, instead of the farm being limited to one payment of $125,000, each individual LLC would qualify for a payment, so the farm operation could benefit from $375,000 in federal benefits (3 x $125,000).

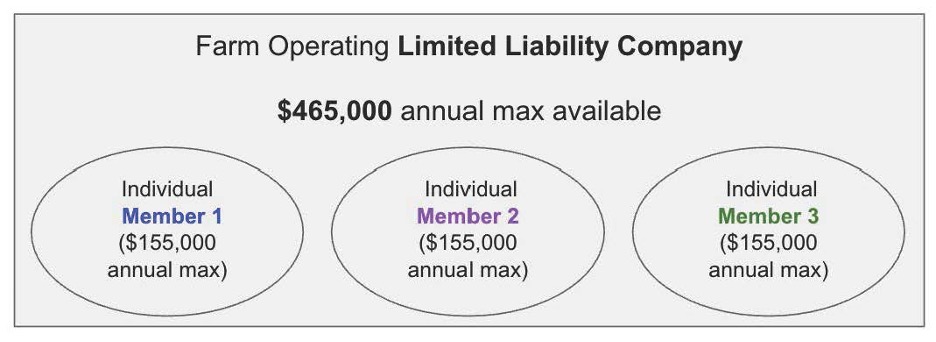

The HB1 provision now places LLCs and S corps alongside partnerships and joint-ventures as pass-through entities for payment limitation purposes. Now, the farm may bypass the step of forming a partnership and organizing individual “partner entities,” and go straight to organizing the farm firm as one LLCs or S Corp. Each individual partner or shareholder who is “actively engaged in farming” will have their own payment limitation, so the farm firm benefits from the individual limitation multiplied by the number of members (LLC) or shareholders (S Corp). The limitation itself – previously set at $125,000 per individual – has also been raised to $155,000 per individual. The Secretary of Agriculture is authorized to increase this amount yearly with inflation. The simplified arrangement – along with the increased payment limit – may be formed as:

Whether farm firms will reorganize may be a matter of cost priority. The higher costs of the arrangement under the old rules came in the form of tax accounting for both the partnership and each individual partner entity, annual filing fees with the secretary of state, plus increased paperwork with the county Farm Service Agency office. For brand new operations, reduced legal fees and state filing fees should offer savings.

Branan, Andrew. “New Federal Law Simplifies Payment Limitations.” Southern Ag Today 5(32.5). August 8, 2025. Permalink