A common question producers ask is, “What is a good price to sell at?” The best answer is that there is no single number that fits every farm. A “good price” is not defined solely by price. It is defined by individual cost structure, yield expectations, and financial goals. One producer with a lower production cost may lock in soybeans at $10.50 per bushel and achieve the same profit margin as another producer who needs $11.50 per bushel to cover higher expenses. The difference is the unique financial conditions facing the operation. Thus, producers must consider various factors when deciding on a “good” price for marketing.

When setting price goals, the cost of production should be the starting point, as it determines the breakeven price when combined with an expected yield. A breakeven price forms the foundation of any pricing decision. Previous Southern Ag Today articles have discussed how to use enterprise budgets to estimate costs and calculate breakeven prices, including Estimating Cost of Production and Breakeven Prices with Enterprise Budgets and Enterprise Budgeting. We encourage producers to revisit these resources to better understand their numbers before establishing price targets.

Once breakeven prices are determined, they must be adjusted to meet the farm’s broader financial goals. An operation cannot remain viable if it only breaks even year after year. Starting with breakeven, producers should begin layering in profit targets that reflect debt obligations, capital replacement needs, working capital goals, and desired returns to management and equity. This stage provides an opportunity to align the marketing plan with the overall financial health and strategic direction of the farm business.

The condition of the farm balance sheet also influences price targets. Producers focused on improving liquidity or reducing leverage may prioritize securing modest but reliable margins. Others in a stronger financial position, or those pursuing expansion, may be willing to target higher price levels before committing bushels. In either case, price targets should reflect the operation’s financial needs and risk tolerance rather than a single benchmark price.

It is also important for producers to understand their local basis when determining price targets. While cash contracts can be used to manage price directly, any futures-based marketing strategy requires accounting for basis risk. Ignoring basis can lead to missed expectations, even if the futures market reaches the targeted level.

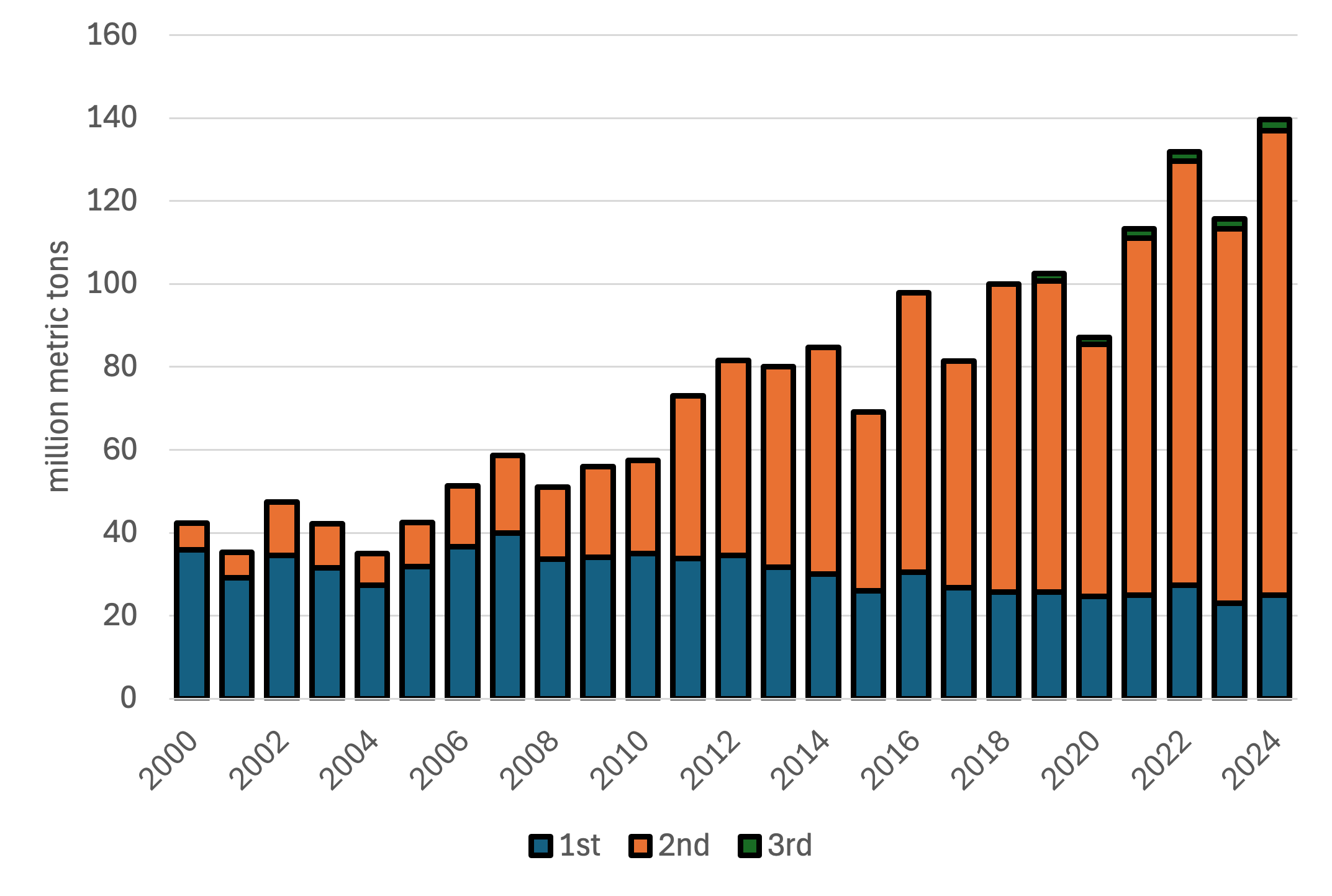

Seasonality can help structure tiered price targets. As shown in Figure 1, the 10 year average soybean futures price, using the November contract pre-harvest and a nearby series post-harvest, tends to rise through the growing season as weather uncertainty builds, soften ahead of harvest pressure, and often strengthen again after harvest as stored supplies are rationed. While this pattern is not guaranteed in any given year, it provides useful context for historically favorable pricing windows. Producers might consider setting an initial pre-harvest target in the spring or early summer when weather-driven volatility supports prices, with additional tiers near typical post-harvest seasonal highs. However, post-harvest targets must account for carrying costs, including storage, interest, shrink, and quality risk, since higher futures prices do not necessarily translate into higher net returns if those costs outweigh the seasonal gain.

Ultimately, a good price is influenced by farm-specific factors unique to each operation. By grounding price targets in cost of production, financial goals, basis expectations, and seasonal tendencies, producers can move from asking “Is this a good price?” to confidently knowing when a price meets their operation’s needs.

Figure 1. Ten-Year Average Soybean Futures Prices Across the Pre- and Post-Harvest Marketing Window

Maples, William. “What Determines a “Good” Price?” Southern Ag Today 6(10.3). March 4, 2026. Permalink