Knowing the expected cost of production for a farmer is essential for developing effective risk management and marketing strategies. At an aggregate level, forecasts of costs provided by the USDA Economic Research Service (ERS) can offer a useful benchmark to help understand the gross revenue and cost of production for commodities at the national or regional level. These forecasts can be used to determine breakeven prices to inform a risk management and marketing plan.

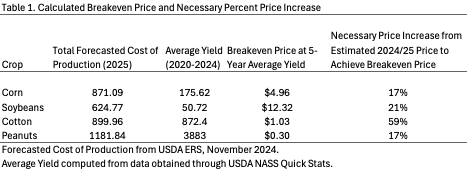

The ERS’s 2025 national cost of production forecast for major southern row crops (cotton, peanuts, corn, and soybeans) indicates a decline in fertilizer and interest costs, contributing to lower total operating cost for most crops compared to 2024, except cotton. However, rising custom rates, other variable expenses, and allocated overhead costs offset some of these savings, resulting in an expected total cost of production that is effectively the same (within +/- 1%) as the estimated 2024 cost of production. As shown in Figure 1, peanuts has the highest forecasted total cost per acre ($1,181.84), followed by cotton ($899.96), corn ($871.09), and soybeans ($624.77), highlighting the significant investment in producing southern row crops. It is important to note that these forecasts were released by the ERS in November of 2024, before tariff threats were made, that if implemented may increase costs of some agricultural inputs, notably fertilizer.

At the currently forecasted cost of production, the negative returns experienced by row crop producers in 2024 are expected to remain a major concern for all four crops in 2025 if prices do not improve. Figure 1 shows the 2024/25 marketing year estimated gross revenue for each crop based on estimated yields and prices as of January 2025. The gap between the two bars on each graph illustrates the potential shortfall in revenue needed to cover 2025 production costs if yields and prices are maintained at current 2024/25 marketing year levels.

Whether yields can provide increased revenue is a question for the future, but given national corn yields in 2024/25 being estimated at record levels and soybean yields being estimated at about 2% below record levels, it is more likely that price is going to be the primary driver to increase revenue for these crops. Meanwhile, multiple weather events made a major impact on cotton yields that were about 12% below record levels and peanut yields that were about 11% below record levels. Therefore, some of the shortfall in revenue for cotton and peanuts could come from higher yields.

The other component of the revenue equation is price. Determining a breakeven price assists in making informed decisions about the price necessary to cover production costs. To determine a breakeven price, divide the forecasted cost of production by expected yield. To help adjust for record yields or significant shortfalls, Table 1 shows the five-year average yield for each crop along with the computed breakeven price. At the current national forecasted cost of production and average yield for the last five years, the breakeven price for corn and peanuts would have to increase 17% over the estimated 2024/25 price. For soybeans, the price would have to increase 21%, while cotton prices would have to rise 59%.

Ultimately, the actual cost of production varies among individual farms, as it depends on many factors such as economies of size and scope, relationships with input suppliers, and adopted management practices. Actual yields also vary, and thus, producers need to consider their own potential breakeven price. Repeating this exercise for a specific farm can be helpful in planning, making risk management and marketing decisions, and finding potential opportunities to make efficiency improvements to reduce costs for the upcoming crop year.