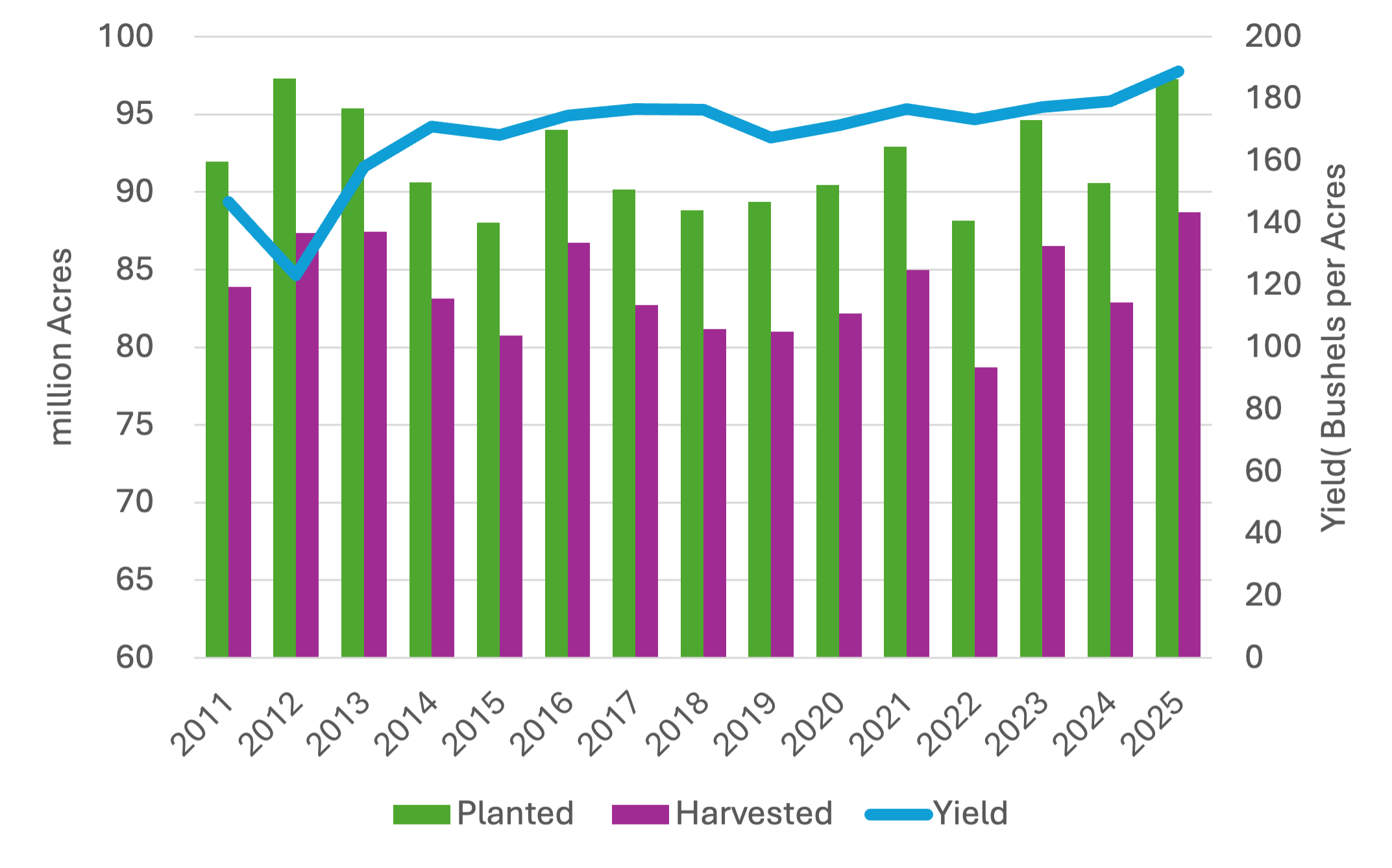

The 2025 grain crop year has presented several challenges, including elevated production costs, significant competition from Brazil and Argentina in the global marketplace, and disruptions in U.S. exports as a result of tariffs. As the midpoint of the 2025 harvest season approaches in the southern region, this year’s grain production is projected to be a second consecutive record crop, while depressed market prices continue. During a year of increased supply, questions arise regarding the availability of grain storage, both on and off the farm, and the potential to delay selling until the market shows favorable prevailing prices. Additionally, producers without on-farm grain storage are burdened with issues of product transportation, off-farm storage availability, and the ability to better control post-harvest grain quality.

Figure 1 shows each of the southern states’ on and off-farm grain storage capacity as of December 2024. The top three states with the most storage capacity are Texas, Arkansas, and Kentucky. In the case of Kentucky, on-farm storage capacity is more than double that of off-farm storage capacity. Oklahoma and Texas have significantly more off-farm storage capacity than on-farm. On-farm storage can play an important role for producers, providing three key advantages to a farm. First, there is the ability to store and hold the harvested crops, allowing flexibility in delivery and the possibility to benefit from higher prices outside of harvest. Maples (2022) illustrates monthly price variations in a previous Southern Ag Today article, showing that May-July were the highest average prices for corn and soybeans from 2014-2021. Second, on-farm storage permits earlier harvest. Assuming bins have dryers, producers can harvest at higher moisture levels and dry the grain before delivery, avoiding moisture discounts. The third advantage of on-farm storage is increased harvest efficiency. Transportation time is less with on-farm storage and is dependable, versus off-farm storage that may be impacted by time spent waiting at the local grain elevator or barge points. This is increasingly important in southern regions where distance to grain buyers can be particularly challenging.

A comparison of grain storage capacity to the total estimated production of corn, soybeans, and wheat in 2025, as well as the average production of the same grains from 2021 to 2024, is also shown in Figure 1. The combination of on-farm and off-farm grain storage capacity exceeds the 2025 estimated production in Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Texas, and Virginia. Meanwhile, production exceeds the combined grain storage capacity in Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee, presenting a potential for marketing challenges if space is not available for the remaining harvest. South Carolina and Louisiana also show production higher than off-farm storage capacity, but on-farm storage capacity data are not available for these states.

The relationship between grain storage capacity and estimated production is important to consider at harvest because when production exceeds capacity, producers generally face having to sell at a negative basis or transport grain farther distances where storage may be available. In a year when excess supply occurs and storage capacity may be strained, there is an increase in the number of producers that are objectively left with the question of, “What do I do with my grain to avoid accepting a really bad price?” Marketing strategies to help answer that question might include deferred pricing contracts, futures, or options, all of which were discussed in a Southern Ag Today article in 2022 and continue to be relevant marketing strategies today.

Notes:: *On-farm storage capacity is not reported for Louisiana and South Carolina.

2025 Estimated Production is the sum of corn, soybean, and wheat production published by USDA as of August.

Florida not shown because on-farm storage capacity data and grain production data are not available.

References:

Maples, William E. “On-Farm Grain Storage in Southern States”. Southern Ag Today 2(38.1). September 12, 2022. https://southernagtoday.org/2022/09/on-farm-grain-storage-in-southern-states/.

Smith, S. Aaron. “Marketing Strategies if Producers Do Not Have Access to On-Farm Storage.” Southern Ag Today 2(40.1). September 26, 2022. https://southernagtoday.org/2022/09/26/marketing-strategies-if-producers-do-not-have-access-to-on-farm-storage/.

Pittman, Wilton, and Adam Rabinowitz. “Marketing Challenges from Storage Capacity and Excess Supply.” Southern Ag Today 5(36.3). September 3, 2025. Permalink