When there isn’t a government shutdown that limits reporting activities, the World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report is a once-a-month shock that does more than nudge the average price. On release days, the intraday volatility pattern—its level across the session, its midday spike, and how quickly that spike fades—differs from ordinary days in ways that traders, merchandisers, and risk managers can plan around. A recent research article evaluated the impact of the WASDE report on commodity futures markets’ volatility (Lee and Park, 2024). Here we translate this research into practical guidance for traders when a WASDE report is released.

Most trading plans benchmark a point estimate—an expected move or a single daily volatility number. But markets trade through time. On WASDE days, volatility is comparatively calm into late morning, jumps right after the 11:00 a.m. Central Time (CT) release, and then eases within about an hour. Treating the day like any other misses the timing and the intraday pattern that drives fills, slippage, and margin exposure.

We study corn and soybean futures from January 2013 through April 2023, focusing on regular trading hours (8:30 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. CT) and explicitly comparing three kinds of sessions: the release day itself, the day before, and the day after. Instead of averaging volatility across the whole day, we recover the intraday volatility curve—how volatility evolves minute by minute. We then ask two questions. First, what does volatility look like on WASDE days relative to other days? Second, is volatility the same across the before/after/release-day split?

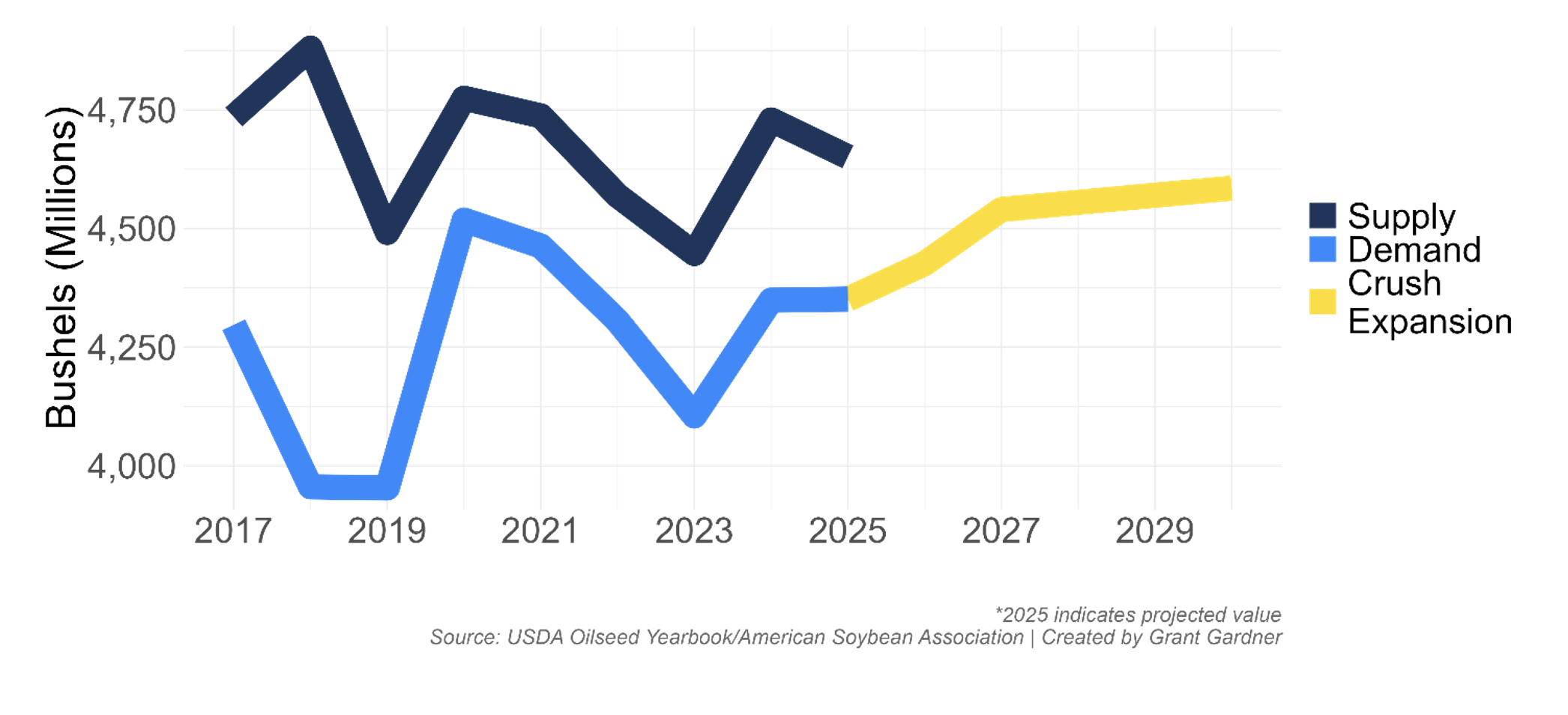

On release days, volatility is subdued at the open, eases into mid-morning, and then spikes right after 11:00 a.m. CT (see Figure 1 and 2). Figure 1 shows the day before and the day after with a simple fade from the open without the midday surge seen on WASDE release days. The spike is visible in both corn and soybeans and typically fades within about an hour, as shown on Figure 2. Formally, release-day intraday volatility differs from the adjacent days, while the before and after pair are statistically indistinguishable. Another practical detail emerges at the open: on release days, when the market’s early-session volatility often starts lower than on non-release days, consistent with traders holding back risk until the report is released. The result is a day that is quieter than usual in the morning, busier than usual just after 11:00 a.m. CT, and fairly normal again by early afternoon.

There are a few key takeaways from this research. One could use smaller orders just before the 11:00 a.m. CT release, then wait 5–15 minutes afterward to see where prices settle before adjusting. If buying, selling, or hedging, skip those first few minutes after 11:00—quotes and spreads are still resetting, and a short wait often saves money. For risk planning, don’t treat the whole day as high-volatility; expect a short, sharp bump around 11:00 that usually fades within about an hour.

While these patterns describe typical release days across a long sample, individual months will differ with the surprise content of the report and with concurrent macro news. The point is not that every WASDE day looks the same, but that the intraday volatility pattern on those days is predictably different enough to plan around. Remember that all trading comes with risks and the guidance in this article is for educational purposes only and is not a guarantee of outcomes.

Figure 1. Intraday volatility up to 11:00 a.m. (Central Time) WASDE release

Figure 2. Intraday volatility on WASDE release days (corn and soybeans)

Minute-by-minute volatility with a 95% confidence band (gray). The vertical dashed line marks the 11:00 a.m. Central Time release. Both markets are relatively quiet into late morning, show a sharp 5–15-minute spike right after 11:00, and then settle toward baseline within about an hour; the exact height of the spike varies by month.

References

- Andersen, T. G., Su, T., Todorov, V., and Zhang, Z. (2024). Intraday periodic volatility curves. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 119(546):1181–1191.

- Lee, K. and Park, E. (2024). Exploring calendar effects: the impact of WASDE releases on grain futures market volatility. Applied Economics Letters, 1–6.

Park, Eunchun. “What WASDE Days Do to Grain Futures: Intraday Volatility Patterns You Can Plan Around.” Southern Ag Today 5(46.3). November 12, 2025. Permalink