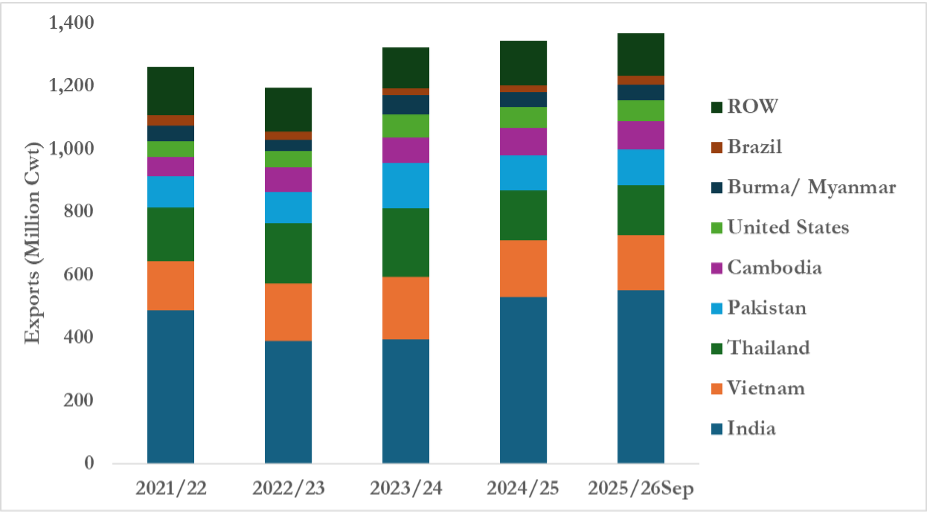

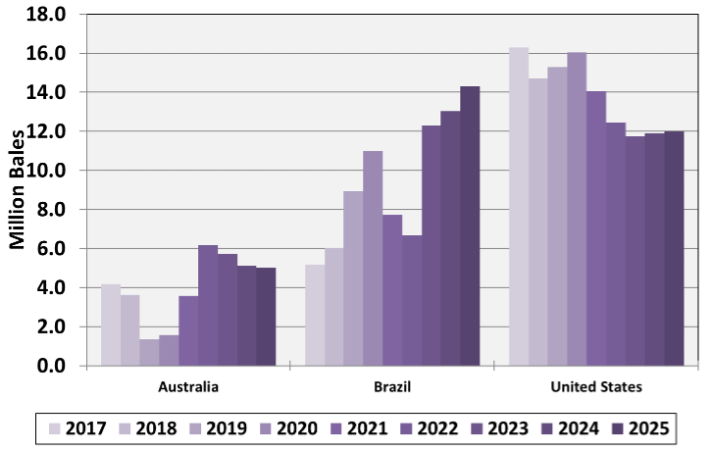

The United States had long been the world’s leading cotton exporter (Figure 1), with 87% of cotton production, on average, destined for export markets over the past decade (2016 – 2025). In 2016, U.S. cotton exports captured 39% of the global market, but this share has steadily declined since the onset of trade disputes with China. By 2023, the U.S. share in the global cotton market had fallen to 26%, its lowest point in over a decade. Although it rebounded slightly to 28% in 2024 and 2025, U.S. cotton has faced rising competitive pressures, particularly from Brazil. Brazil’s ability to double-crop cotton with other crops has driven substantial growth in its cotton production and exports. Consequently, Brazil has rapidly expanded its role in the global cotton market, surpassing U.S. cotton export volumes by 2023 and becoming the world’s leading cotton exporter. This shift is closely tied to China’s strategic diversification away from U.S. cotton, with Chinese investment in Brazilian infrastructure improving logistics, port access, and overall competitiveness.

Cotton prices received by producers across countries vary only slightly, with Brazilian cotton producers typically receiving marginally lower prices than their U.S. counterparts. Although Brazilian cotton producers face higher seasonal costs per acre for fungicides and insecticides due to the tropical climate, these expenses are more than offset by advantages in land, labor, and machinery costs. Consequently, Brazil’s overall production costs per acre for cotton are slightly lower than those of the U.S. producers, reinforcing the former’s competitiveness. Moreover, USDA FAS data indicate that Brazilian cotton yields from 2021 to 2024 averaged 1.8 times that of U.S. yields, resulting in significantly lower costs per pound of cotton produced. Since Brazil’s production costs for cotton remain below market prices, its cotton producers have continued to operate profitably, enabling expanded production. As a result, Brazil’s cotton output has surged, and by 2023, it had surpassed U.S. cotton production, becoming the world’s third-largest cotton producer after China and India. In contrast, U.S. cotton producers have faced production costs exceeding gross revenues, leading to financial losses since 2022 (Liu 2024), coincidental with a severe drought that year in the U.S. Southern Plains.

The global cotton market is undergoing significant shifts, with Brazil emerging as a leading exporter and the United States facing new competitive pressures. Brazil’s ability to expand production efficiently, combined with China’s strategic diversification, has reshaped export patterns and global market shares. For U.S. producers, this evolving landscape underscores the importance of monitoring international market trends, production costs, and trade relationships. While challenges exist, understanding these dynamics can help growers make informed planting, marketing, and risk management decisions, ensuring continued competitiveness in a changing global market.

Figure 1. Top Three Global Cotton Exporters by Country and Year.

Liu, Yanguan, Gopinath Munisamy, and John Robinson. “How Brazil’s Rise in Global Cotton Markets Impacts U.S. Exports.” Southern Ag Today 5(41.3). October 8, 2025. Permalink