Financial record keeping is an important aspect of farming. Tracking how your farm is doing over time can help you diagnose any potential issues that may arise. Having an accountant can help you understand how your farm is doing financially and prepare your tax returns. To save time and money, it is essential to provide your accountant with accurate records that reflect what actually happened on your farm. Mislabeling an income or expense can lead to incorrect categorization that will take your accountant more time to correct and/or could create a higher tax bill.

You know your farm better than your accountant, and the more detailed records you have on your farm, the better they are going to be able to help you prepare your financial documents. The following are some tips to make your records more organized for your accountant:

- Keep business and personal expenses separate.

- If the farm bank account is used for a personal expense, make a note of it.

- In a sole proprietorship or general partnership, what is personal and business use might be unclear, so it is useful to track all income and expenses.

- In a limited partnership, limited liability company (LLC), or corporation, you must use separate accounts for personal and business use.

- Record information on each income and expense transaction.

- Each income transaction should have the following: Date, Reference Number, Purchaser, Amount Deposited, and the Type of Income.

- Each expense transaction should have the following: Date, Check/Reference Number, Payee, Amount Paid, and the Type of Expense.

- Write legibly on checks and leave a note in the memo line as to the purpose of a purchase.

- Clear and detailed information on each check will help you and your accountant decide how to categorize checks for tax or management purposes.

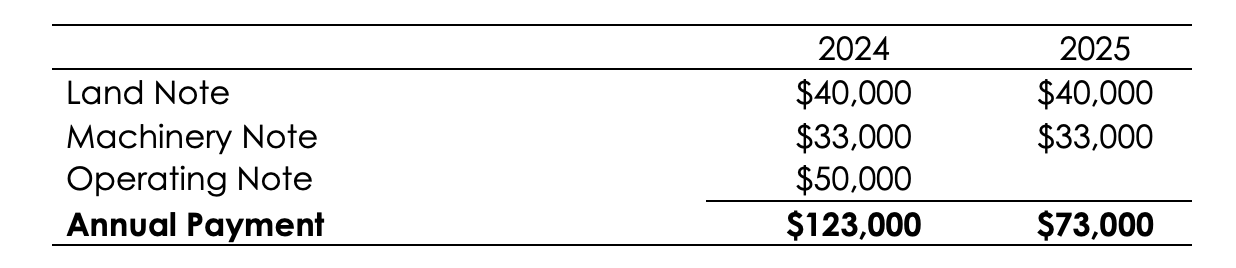

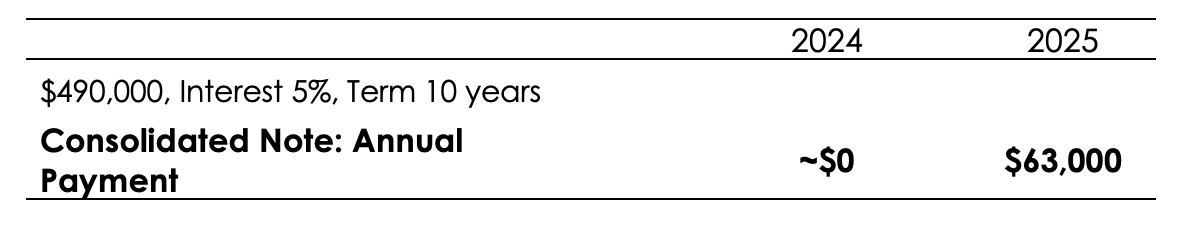

- Have the principal and interest payment figures separated for any fixed asset loans.

- This can be found on the last statement of the year or a 1099 from the entity you are paying.

- For any contract laborer who is paid more than $600 within the tax year or any employee for whom you pay payroll taxes, your accountant will need that person’s social security number and address to file a 1099 or W-2 form for those workers on your behalf.

- Consult your accountant for information on paying the proper payroll taxes for any farm worker.

This list is just a starting point for what you need to think about before visiting your accountant. Again, you know your farm better than your accountant, so the more information you can bring to your accountant, the better they will be able to help you. This will save both your accountant’s time and your money. It will also allow you to get a better understanding of how your farm is doing financially. In both good and tough years, it is important to know your full financial situation so that you can plan accordingly.

Mills, Brian E., Kitty Charlton, and Kevin Kim. “What to Bring to Your Accountant.” Southern Ag Today 4(53.1). December 30, 2024. Permalink