Southern agriculture faces unique challenges, with limited crops that are both suitable and competitive in the region. Cotton, one of the major row crops in the Southern United States, has historically been favored for its drought resistance, making it well-suited to the region’s soil and weather conditions. Cotton is grown from Virginia to California across the southern U.S. In 2024, the U.S. is projected to produce 14.5 million bales of cotton. While market prices are expected to be around $0.66 per pound (USDA WASDE), the value of cotton production is approximately $4.6 billion nationwide, underscoring its essential role in the Southern region.

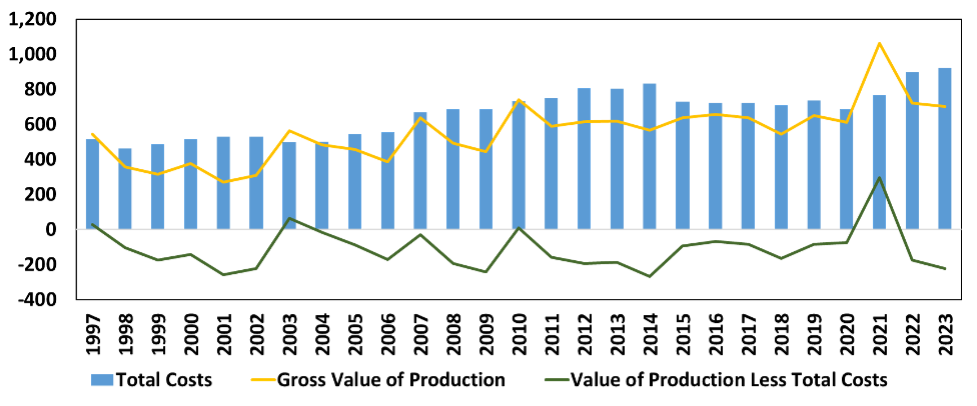

Recent data from the USDA’s Economic Research Service highlights the complexities of cotton farming, showing that growers have faced financial challenges over the years. The data in Figure 1, covering the period from 1997 to 2023, highlight the ongoing profitability challenges Southern cotton farmers face. This data accounts for all costs incurred by participants in the production process, including farm operators, landlords, and contractors. The data reflects the actual production costs incurred by cotton farmers, including expenses for labor, equipment, and other inputs, as well as the revenue generated from cotton sales. However, these figures do not include government payments and crop insurance indemnities received by producers during this period. The government payments include traditional farm bill programs for farmers with base acres, as well as ad-hoc disaster relief programs.

In competitive commodity markets, where agricultural goods compete under perfect competition, economic theory suggests that profits attract more producers. This increase in supply drives prices down, eventually reducing profitability. Over time, long-term economic profitability tends to stabilize around zero, which becomes the level needed for economic sustainability for the industry. Producers are compelled to become more efficient in their operations to achieve profitability above this threshold. However, over the 27-year period, cotton only managed to exceed total production costs in four years. On average, cotton growers faced annual losses of $94 per acre, highlighting the crop’s ongoing struggle to cover production costs.

This consistent lack of profitability is unsustainable for cotton producers. Farmers’ inability to cover total costs, including fixed expenses like long-term asset depreciation for buildings and equipment, presents a serious risk to the agricultural future. Many farmers are increasingly relying on personal equity to keep their operations running, a practice that is financially unsustainable in the long term. As a result, many are turning to government support, including farm bill programs and disaster relief initiatives, which can provide a safety net during challenging times.

With long-term economic loss for cotton production, the economic health of Southern agriculture and the livelihoods of its farmers are at risk. If this issue is not addressed, it could result in a prolonged decline in agricultural production, eroding the economic foundation of farming communities across the Southern region.

Figure 1. Cotton Production Total Costs, Revenue, and Returns for Producers in the United States (1997 – 2023).

References:

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Economic Research Service (ERS), Commodity Costs and Returns for Cotton, Updated on 10/1/2024.

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE), WASDE – 652, September 12, 2024.

Liu, Yangxuan. “The Long Term Economic Struggles of Southern Cotton Farmers.” Southern Ag Today 4(44.1). October 28, 2024. Permalink