Authors Joe Outlaw and Bart L. Fischer

We have all heard the old proverb “it takes a village to raise a child.” Indeed, an entire community is needed to interact with and guide a young person to grow into a well- rounded adult. If the last 2 years are any proof, the same could be said about farm policy. Against the backdrop of exploding input costs and falling prices, the various components of the Federal government ultimately came together to begin addressing the bleak economic outlook. For example:

- While Congress was unable to get a farm bill done in 2024, they ultimately provided $30.78 billion in assistance for both economic and natural disaster losses from the 2023 and 2024 crop years. Within 90 days of passage, the newly minted Secretary of Agriculture, Brook Rollins, had implemented the Emergency Commodity Assistance Program (ECAP) and quickly followed with the initial round of the Supplemental Disaster Relief Program (SDRP).

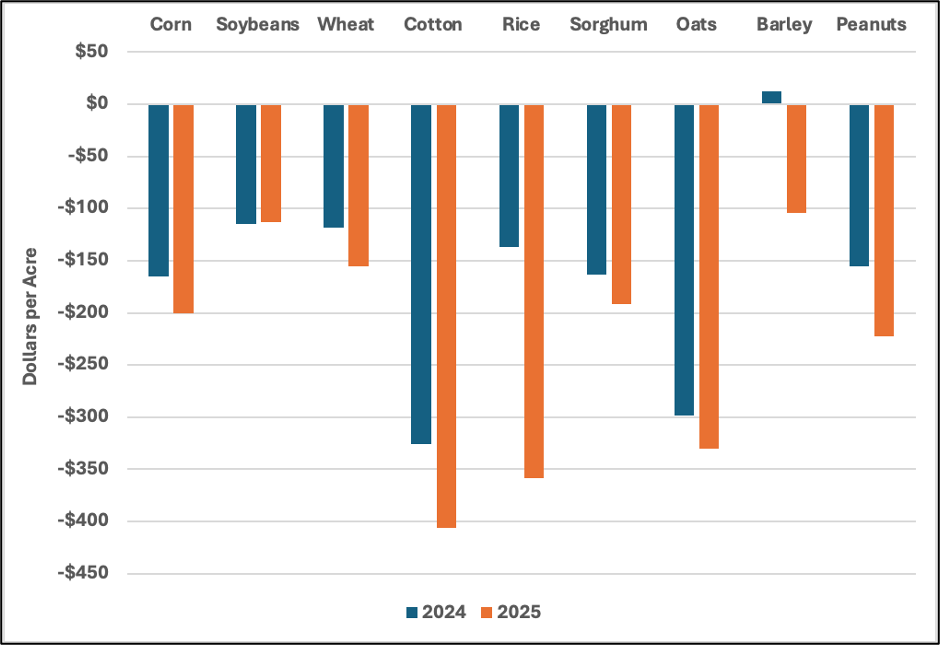

- As 2025 unfolded, when it became apparent that a bipartisan farm bill was unlikely, the Chairmen of the House and Senate Agricultural Committees along with the leadership in each chamber and the administration worked to include more than $60 billion in enhancements to the farm safety net in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA). OBBBA was passed through the reconciliation process and was signed into law on July 4th of last year, with the enhanced provisions taking affect for the 2025 crop which was already well underway. While the marketing year average prices that determine the amount of assistance are still being determined, it is safe to say that all of the efforts that were put into getting the enhanced safety net provisions in the OBBBA will be felt and greatly appreciated by producers when payments are distributed after October 1st for those crops that trigger assistance. And, at the moment, it looks like virtually all crops will trigger.

- As we approached the end of 2025 with economic and trade-related losses still outstripping the assistance that will eventually arrive under the OBBBA, the Trump Administration stepped in and announced the creation of the Farmer Bridge Assistance (FBA) program that will inject an additional $12 billion of operating capital on farms by the end of February.

- The agricultural leaders in the U.S. Congress are considering taking this even further, with some reports suggesting yet another $15 billion in assistance could go out the door to address other 2025 crop year losses, including those of special crop and sugar producers that were not included in FBA and have yet to be addressed by USDA.

Getting the regulations completed for all of these program changes—and for the new programs—takes the effort of everyone from the Farm Service Agency (FSA) and Risk Management Agency (RMA) at USDA to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in the White House to the congressional agricultural committee staff, just to name a few. Despite all of the disfunction and infighting in Washington, “the village” has still managed to come together to make positive changes to address the bleak outlook facing U.S. farmers.

Outlaw, Joe, and Bart L. Fischer. “It Takes a Village.” Southern Ag Today 6(4.4). January 22, 2026. Permalink