Authors: Jose Andres Solis and Chrystol Thomas

Rural land values in the U.S. sit at the intersection of agriculture, housing, energy, and long-term investment. Land values influence producers’ borrowing capacity and decision making while they influence households’ wealth and tax burdens, affecting the prosperity of rural communities. There was an increase in rural land and property values in the wake of the pandemic, due in part to high buyer demand. Remote workers were able to relocate from cities to rural areas as broadband access (high-speed internet) expanded and rural infrastructure improved in more remote regions (Smith, 2023), resulting in an emerging trend across the U.S. that further increased demand for rural land. Understanding the factors affecting rural land values help determine the resilience of farm operations and the affordability of rural living, both of which are important to the development of rural communities. This becomes even more pertinent given the recent shift in interest rates, along with the volatile nature of commodity prices, and growing competition for land from investors for various purposes such as renewable energy projects.

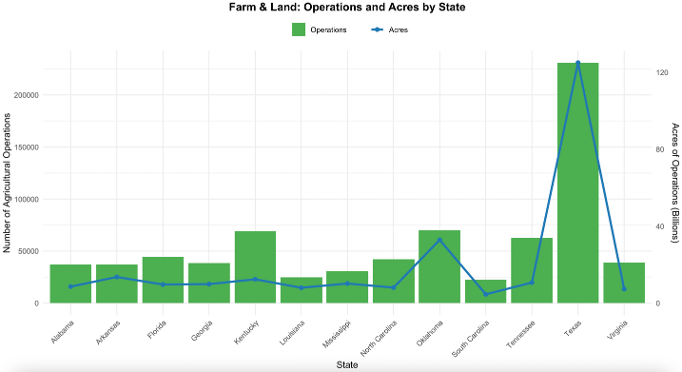

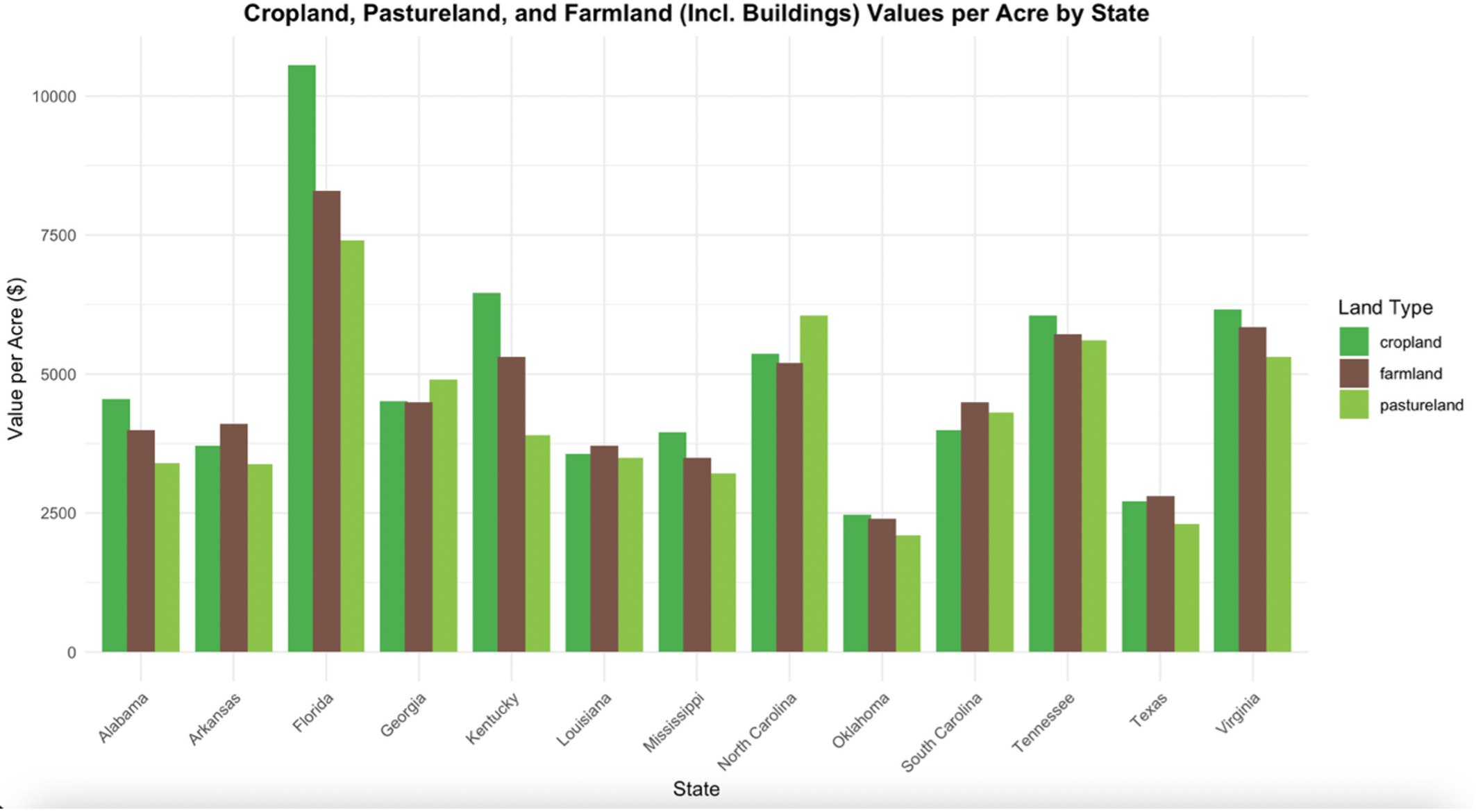

Texas is known for its rural character, having the most farmland in the country and by far the largest amount in the southern region (U.S Census, 2022, see Figure 1). Despite the state having one of the lowest land values in the region, second only to Oklahoma (Figure 2), its land value increased by about 55% over the past 10 years (Smith et al., 2025). Average per-acre land prices increased from $1,951 in 2017 to $3,021 in 2022, mostly driven by an increased recreational use potential (Smith et al., 2025). The 2024 Texas Land Trends report found that rural land values were highly influenced by demand for lifestyle-oriented buyers and investors rather than traditional farm income from production (ASFMRA-TX, 2024). Rural land in Texas was valued at nearly $300 billion in 2021, representing about 10% of the total rural real estate value in the U.S. (Su et al., 2024). Although farm income and commodity prices have shown peaks during the past decade, they have since returned to more stable levels, placing a significant financial burden on both new buyers trying to enter the market and long-time landowners struggling to hold on to their property. According to the ASFMRA- TX (2024), the strongest increases in land value in rural Texas were observed in Central Texas (48%) and the Upper Gulf Coast Region (12%) given their proximity to intense growing urban centers like Austin and Houston, respectively. In contrast, Far West Texas showed the slowest growth in value. Gilliland et al. (2020 & 2010) alluded to the sparse population, lack of urban development, and limited agricultural infrastructure as factors influencing the low land values in this region.

To examine the factors that influence land values, this article uses Washington County in Texas as an example. The county is in the Blackland Prairies region of southeast central Texas, an area influenced by its proximity to urban centers and its availability to those markets. Specifically, a 250-acre case study property was examined. The site features hilly topography, a mix of wooded and open areas, recreational infrastructure, and five building improvements, including a main house overlooking a small lake. To analyze the property’s market value and the factors influencing it, data from 136 comparable property sales in the county were used. A simple regression analysis was performed to identify significant factors that influenced land prices. The variables used in the analysis to determine the factors that influence property values in Washington County were minutes to Brenham (urban center), percentage of surface water, percentage of floodplain, percentage of wooded area, plot size, and market conditions.

The variables found to have a statistically significant impact were reduced drive time to Brenham (urban center), percentage of surface water, percentage of floodplain, and market conditions. The regression analysis showed that for every 5-minute increase in drive time to Brenham, land value decreased by 12%, while each 0.5% increase in surface water coverage added 5% to property value. Similarly, properties with more floodplain coverage saw a reduction in value by 4% for every 5% increase in floodplain, reflecting the risk for recreational buyers. Market conditions showed that land values are rising at about 1% per month, highlighting the constant rising demand. A characteristic that is important to note is that land size was deemed statistically insignificant, reinforcing the idea that amenities and accessibility influence more than acreage in recreational markets.

Washington County serves as an example of how non-agricultural factors are driving rural land valuation in Texas. Multiple factors influence land values in Texas that extend from traditional farm income and production capabilities. The statistical analysis done highlights that the tract location and accessibility are the factors that influence land value the most. As land near major cities often has a market rate significantly higher than those in remote areas. In Washington County, for example, public road frontage was found to be the most significant quality for impact on land prices, reflecting the importance of development potential and easy access. Soil quality and water availability also play major roles as fertile land and reliable water sources reduce production costs and enhance productivity (ASFMRA-TX, 2024). Other than traditional agricultural uses, recreational demand has become a powerful driver of land value, especially during the pandemic in 2020, when individuals sought for a rural homesites as comfortable retreats, prioritizing lifestyle and recreation over traditional farm income (Smith, 2023). Additionally, infrastructure and government incentives shape land value by determining how a tract of land can be used and improved. Research show that non-farm factors now play a crucial role as commodity prices or farm returns, highlighting the complex nature of Texas rural land valuation (Su et al., 2025).

Understanding the key drivers of rural land value, especially in counties like Washington, has various implications for a wide range of buyers. Landowners and investors can use this information to make more informed decisions about when and where to buy, sell, or how to develop rural properties, especially as recreational demand continues to rise. Local governments and planners benefit by recognizing how access to land, water features, and proximity to urban areas influence land use trends and can proactively manage growth through development and zoning decisions. Moreover, developers can use these findings to balance the competing interests of development and land preservation, especially in high demand areas. The growing trend of recreational land and displacement from agricultural income also raises concerns for new farmers and policy makers.

Figure 1. Farm & Land: Operations & Acres by State, 2024

Figure 2. Cropland, Pastureland, and Farmland (including buildings) Values per Acre by State, 2024

References:

American Society of Farm Managers and Rural Appraisers, Texas Chapter (ASFMRA-TX). (2024). Texas rural land value trends 2024. ASFMRA Texas Chapter.

Gilliland, C. E., Greaves, S., & Su, T. (2020). Structural trends of regional Texas rural land markets. Texas Real Estate Research Center at Texas A&M University. Available at: https://trerc.tamu.edu/article/structural-trends-regional-texas-rural-land-markets-2279/ (Accessed: 11 July 2025).

Gilliland, C. E., Gunadekar, A., Wiehe, K., & Whitmore, S. (2010). Characteristics of Texas land markets — A regional analysis. Texas A&M University Real Estate Center. Available at: https://trerc.tamu.edu/wp-content/uploads/files/PDFs/Articles/1937.pdf (Accessed: 11 July 2025).

Smith, R. (2023). Southwest land values up: COVID played a role. Farm Progress. Available at: https://www.farmprogress.com/farm-life/southwest-land-values-up-covid-played-a-role (Accessed: 11 July 2025).

Smith, L.A., Lopez, R.R., Lund, A.A., & Anderson, R.E. (2025). Status Update and Trends of Texas Working Lands 1997 – 2022. Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute, College Station, TX, USA. Available at: https://nri.tamu.edu/media/y04fu4b3/status-update-and-trends-2025-full-report.pdf (Accessed: 10 December 2025).

Su, T., Dharmasena, S., Leatham, D., & Gilliland, C. (2024). Texas rural land market integration: A causal analysis using machine learning applications. Machine Learning with Applications, 18, 100604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mlwa.2024.100604.

Su, T., Dharmasena, S., Leatham, D., & Gilliland, C. (2025). Modeling influence of agricultural and non-agricultural factors on Texas rural land market values. In Preprints.org.

https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202503.1016.v1.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Nation’s Urban and Rural Populations Shift Following 2020 Census. Available at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/urban-rural-populations.html (Accessed: 31 December 2025).

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service (USDA-NASS) (2025). Available at: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Data_Visualization/Commodity/index.php (Accessed: 10 December 2025).

Solis, Jose Andres, and Chrystol Thomas. “Drivers of Change in Rural Land Values: The Case of Texas.“ Southern Ag Today 6(2.5). January 9, 2026. Permalink