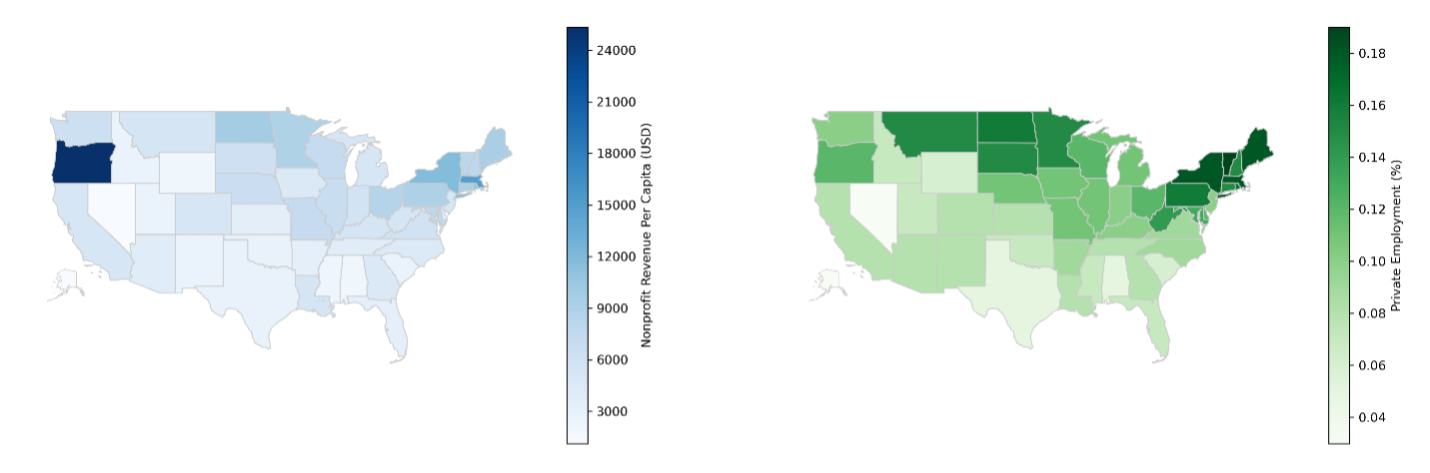

Specialty crops are historically, and currently, labor-intensive enterprises. Labor costs typically range from 30-40% or more of total annual operating costs. Additional labor in packing, grading, distribution, and other supply chain activities makes this sector especially vulnerable to supply limitations and cost increases. The H-2A program, a program farmers rely on to meet their labor demand increased almost three-fold in the past decade. Approximately 75% of these workers were employed in the US specialty crop sector in 2024 (Figure 1). This growth in employment has happened despite significant increases in the adverse effect wage rate (AEWR) in the last years.

An expected response to the higher labor costs facing the US specialty crop farmers includes investments in technological alternatives. Automation, however, is often difficult to quickly implement as a substitute factor of production and includes high learning costs. Additionally, size and scale economies tend to dictate where adoption may or may not be feasible in the field or packing line.

To provide deeper insights into potential solutions for smaller SE US specialty crop growers, we gathered responses from produce industry leaders nationwide, who weighed in on labor saving technology substitution strategies. They shared the following valuable observations in response to the prompt: If there’s a labor-technology shift underway, could this prove too difficult for small farm agriculture?

“Most labor technology is larger scale, and even though it has come a long way, harvest for fresh market and what is needed for quality in a timely way is a long ways away.” Chris Falak (Gerber Grower direct farm sourcing)

“The industry is driven to use technology to replace labor, and the wage rate is ever increasing as well as other input costs. So far, innovations include optical packing lines, robotic and drone type sprayers and field disease detection. It will be difficult for small farms to absorb the increase in cost as the initial technology is cost prohibitive given a small number of acres.” Greg Cardamone, L& M Produce

“There could be barriers to entry for high-tech production ag equipment but there are also amazing opportunities to include better business management software, AI, and other technologies to help with management costs, sales, procurement, and supply chain. Those advantages could be easier for small farms to adapt verses larger incumbents that already have huge sunk costs in old ways of doing things. Small farm agriculture can also be better at hitting niche, low volume but high margin markets that are too finicky for large scale operations.” Cory Reinle, Nestle Produce Procurement Leader, formerly with Pero Farms and Winn-Dixie

“Definitively costly yet more sharing equipment/solutions and more IT companies adapting to smaller farmers by leasing vs. selling; pricing adjustments. The only concern here is that unless they start getting paid higher prices, they do not seem sustainable for the costs incurred. The owners are also concerned that training workers on new technology is time consuming for such short times of usage. This is a question mark for the future for small farmers.” Martha Montoya, CEO Ag Tools

“It will definitely present challenges, particularly in terms of capital investment and technical capacity. However, small farms still hold strategic advantages. They can differentiate themselves through direct-to-consumer marketing, local branding, and agility in responding to niche market demands. Moreover, diversification away from traditional growing regions—whether due to climate, labor, or logistics—can enhance supply chain resilience. Proximity to end consumers also reduces food miles and improves freshness, offering small farms a competitive edge even if they adopt technology at a slower pace.” Molly Tabron, Robinson Fresh

We identified two key takeaways emerging from the viewpoints of these industry experts that may provide smaller SE US produce growers with useful information:

- As fast as technology has developed to support farm and post-harvest activities, pivoting away from the status quo will be slow. In some ways, smaller farms have advantages where they utilize less total labor and produce for niche markets that pay a high-quality premium. They may have less incentive to pivot toward more automated systems.

- Automation related to management tools that can be used across supply chains may be under-appreciated as part of this revolution. Tools that can better facilitate the handling of high value perishable crops may have a larger impact on managing costs and adoption may not be as scale dependent.

In sum, the dynamics of labor cost and utilization will remain a central issue for the specialty crops industries for easily the next decade. Farms, industry partners, policy makers, and the ag technology trade need to work together to support labor and technology development for this industry that is characterized by highly segmented markets and variable production systems.

Figure 1.

Notes:

The author wishes to express thanks to the industry leaders that have contributed to the perspectives shared in this article. This was part of a special session organized by the Specialty Crops Section of the American Agricultural and Applied Economics Association annual meeting which took place in Denver, Colorado, on 28 July 2025. Session presenters, Maria Bampasidou, Elizabeth Canales, Karina Gallardo, Kuan-Ming Huang, Kim Morgan, Suzanne Thornsbury, and Tim Woods, are members of the S1088 Specialty Crops and Food Systems: Exploring markets, supply chains and policy dimensions. Figure 1 shared here by Bampasidou and Canales from their presentation titled “Labor Considerations: Observations from Southern States”.

Woods, Tim. “The Labor-Technology Shift for Smaller Southeastern U.S. Specialty Crop Growers.” Southern Ag Today 5(35.5). August 29, 2025. Permalink