Disconnected youth, individuals aged 16 to 24 who are not in school or working, have become a growing concern in the U.S. over the past two decades (Crockett & Zhang, 2023). Disconnection from both education and employment can lead to long-term consequences, including delayed life milestones, reduced productivity, and a weakened workforce.

While disconnected youth are shaped by a complex mix of influences, community programs offered by local organizations, including nonprofits, Cooperative Extension Service, workforce development agencies, and youth-serving groups, may provide a promising pathway to engagement. Many of these programs offer mentorship, job training, educational support, leadership development, and connections to local networks that help young people build confidence, develop skills, and find direction for sustained engagement in education or the workforce.

To explore this possibility, a nationwide online survey was conducted from March 7th to 17th, 2025, with 1,031 randomly selected individuals aged 18 to 24 (those under 18 were excluded to avoid the need for parental consent). The survey focused on respondents’ experiences and perspectives regarding participation in community programs that support education and career development, which are areas they are often disconnected from.

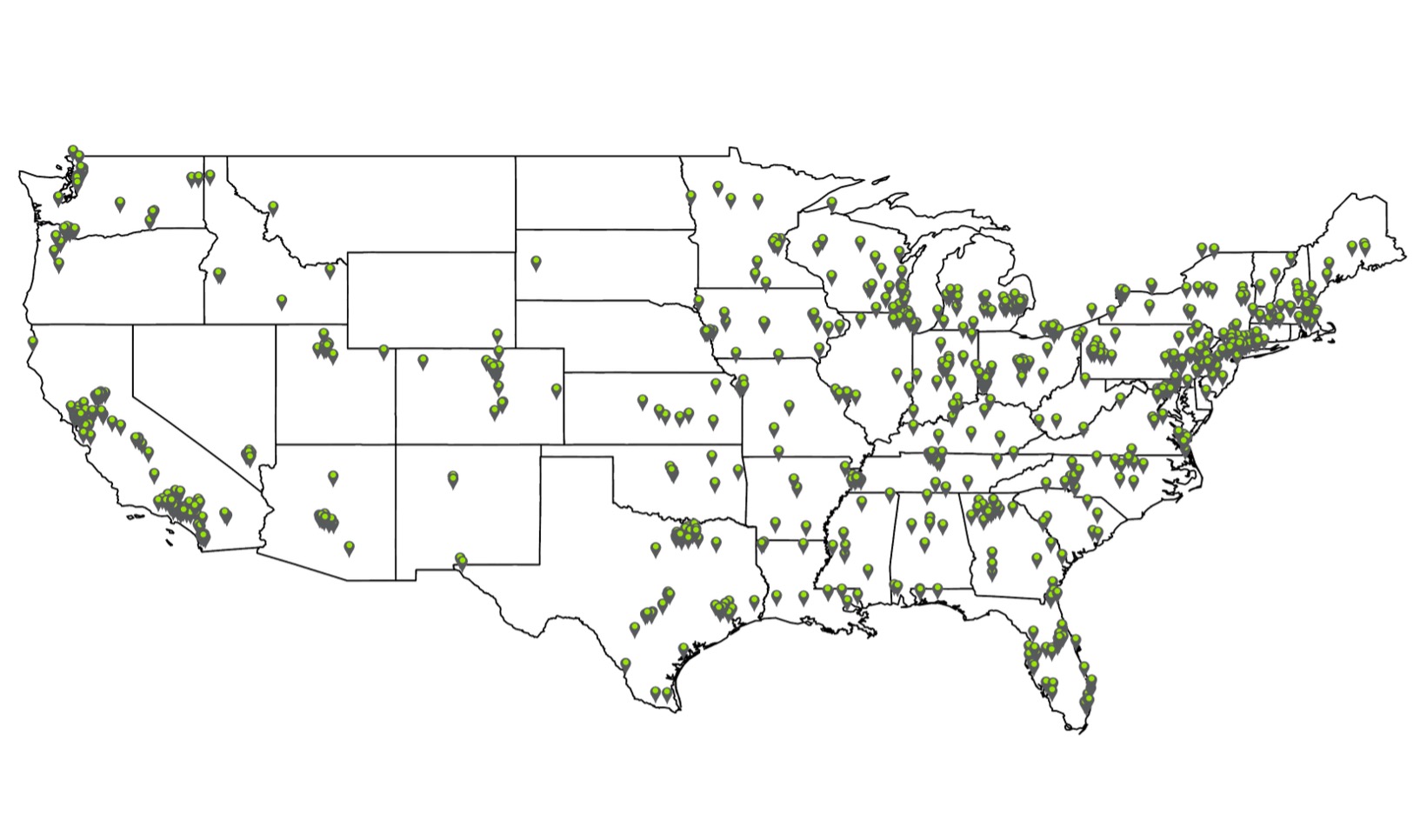

Figure 1. A map of the Survey Responses (n = 1,031)

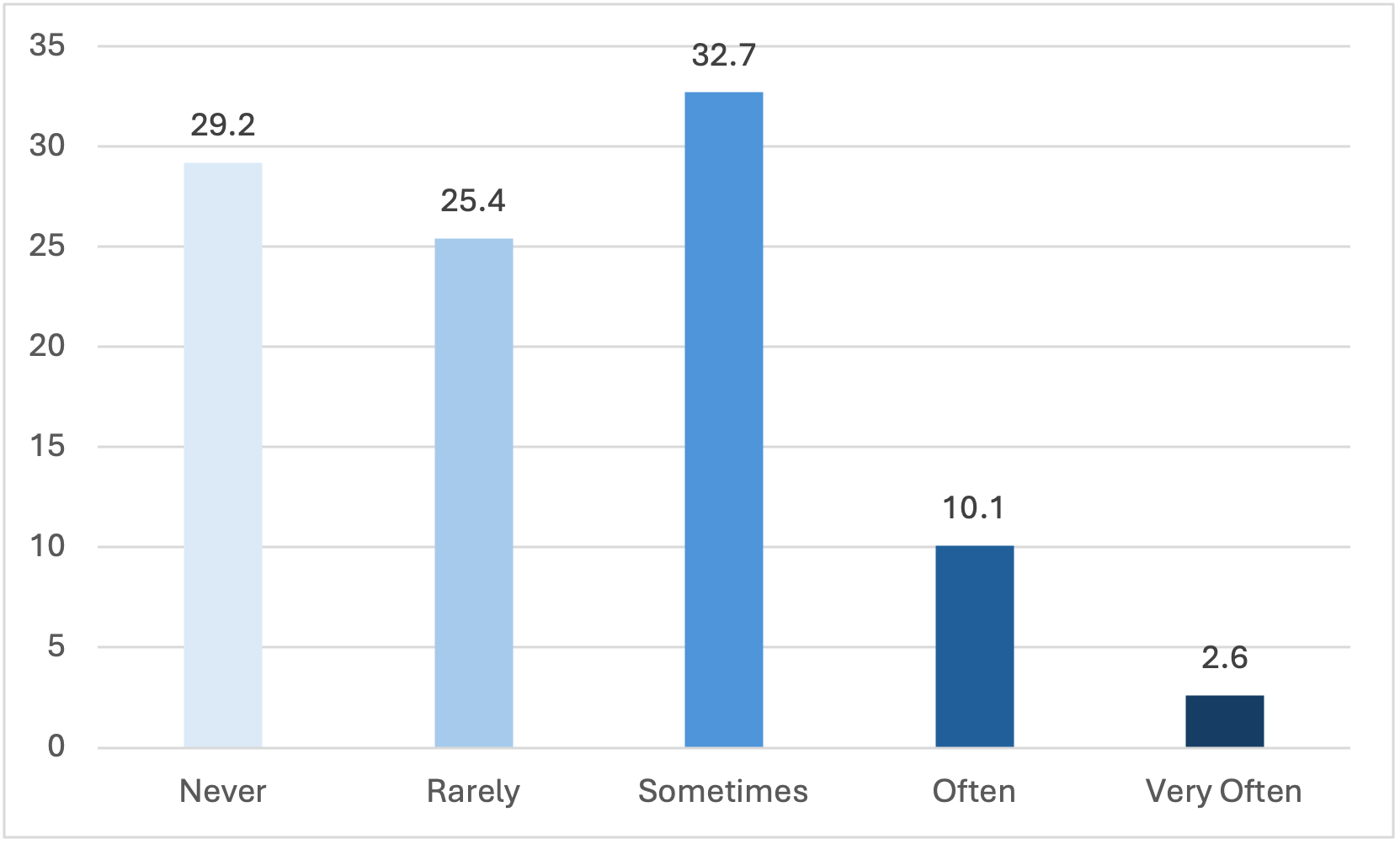

First, the survey asked respondents how often they had received support from community programs, including mentorship, job training, youth development, education, or tutoring (Figure 2). Approximately 29.2% reported never receiving such support, while the remaining 70.8% indicated some level of participation. Most respondents said they received support either “sometimes” (32.7%) or “rarely” (25.4%), suggesting limited but notable engagement. A smaller portion reported more frequent involvement, with 10.1% selecting “often” and just 2.6% selecting “very often.”

Figure 2. Frequency of Support Received from Community Programs (Unit: %)

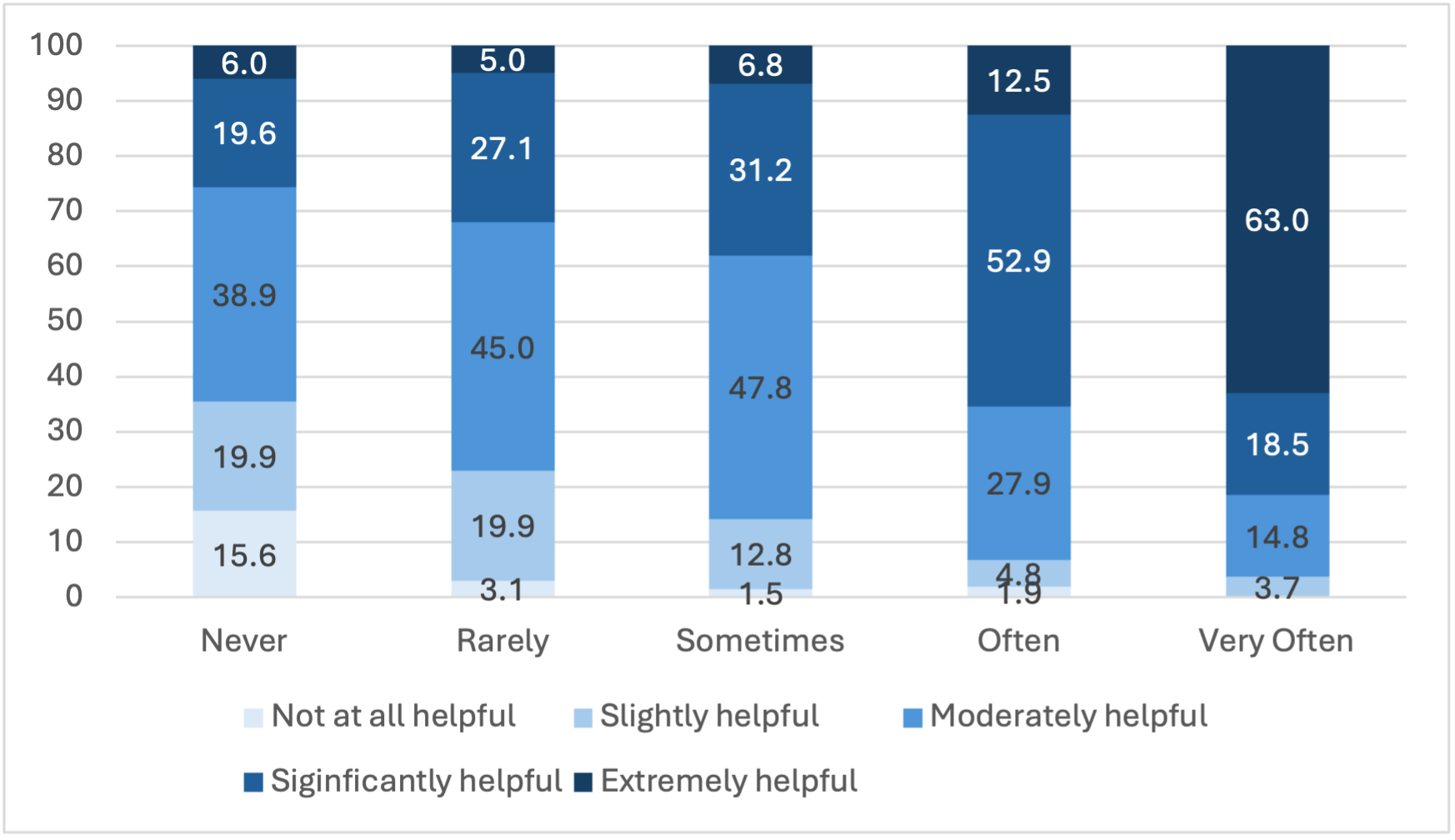

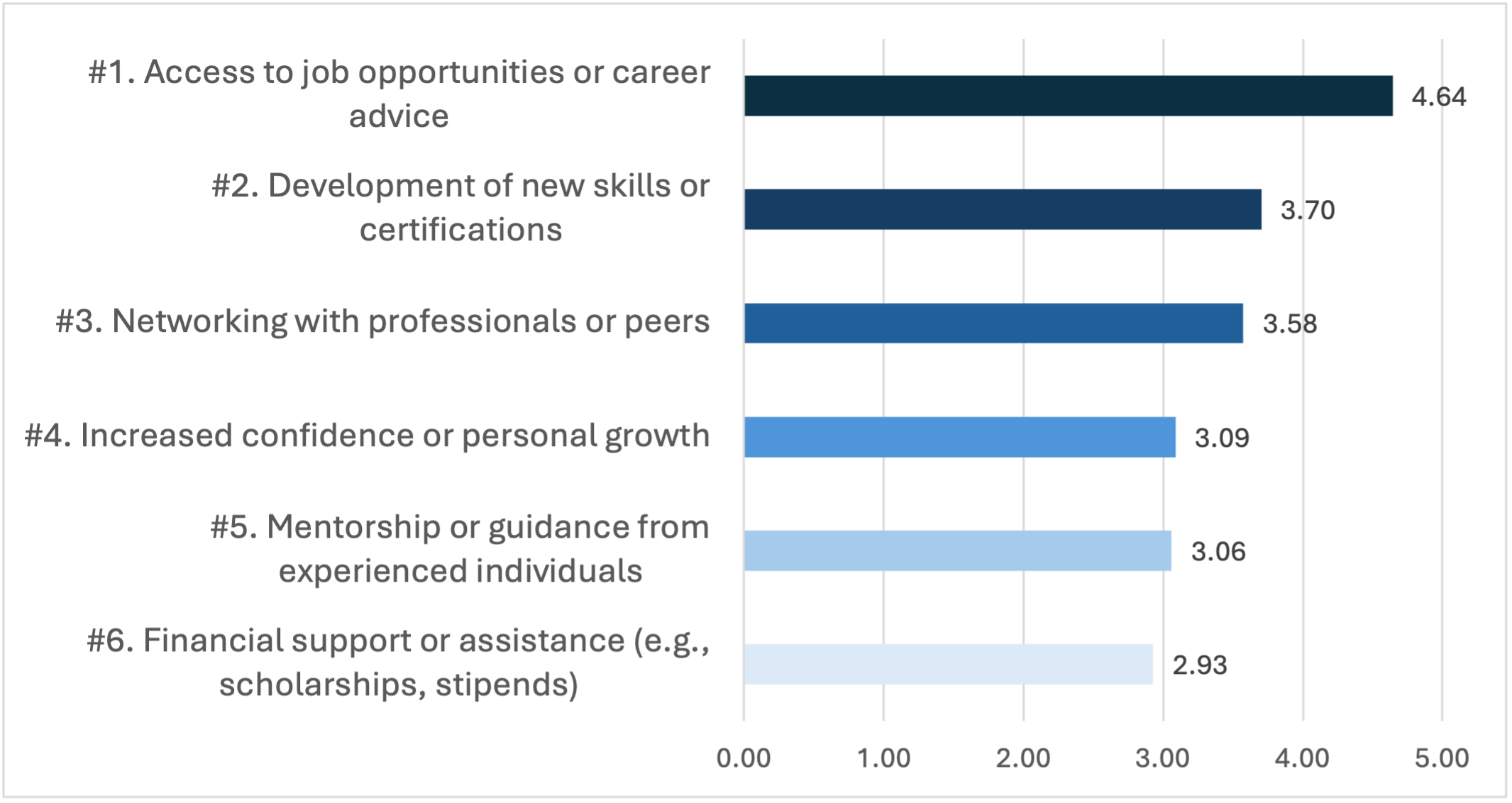

More notably, respondents who participated more frequently in community programs were more likely to perceive them as highly beneficial for their education and career, suggesting a substantial positive impact of such programs (Figure 3). But what exactly are young adults looking for in these programs? When asked to rank six types of community programs based on their perceived impact on education and career outcomes, the majority of respondents chose “Access to job opportunities or career advice” as the most helpful, while “Financial support or assistance” received the lowest ranking (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Perceived Helpfulness Levels by Frequency of Program Participation (Unit: %)

Figure 4. Average Importance Ratings of Community Program Benefits by Perceived Impact on Education and Career

(1 = Least Important; 6 = Most Important)

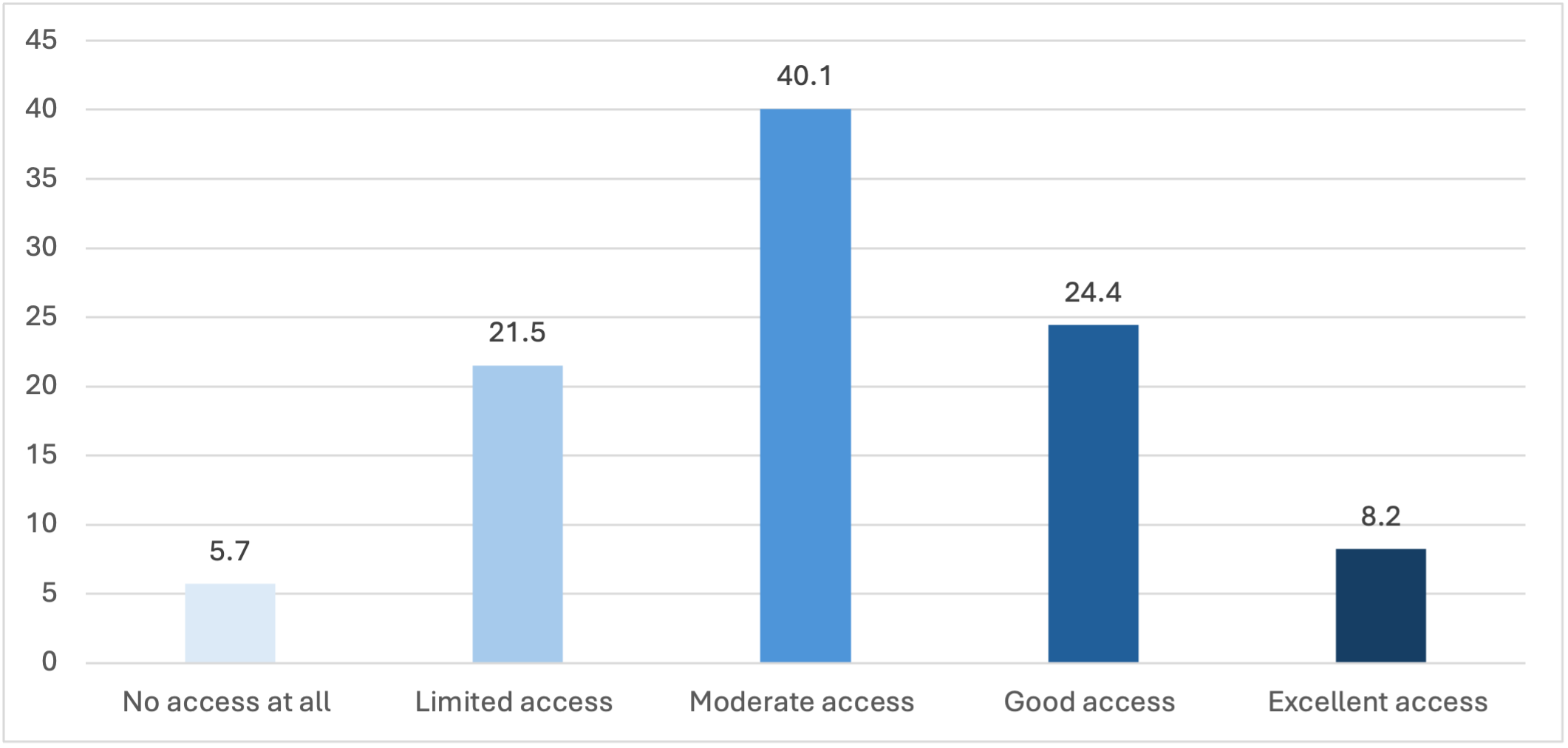

What about accessibility to community programs? The survey asked whether respondents had access to local initiatives such as mentorship, job training, youth development, or tutoring services (Figure 5). Only about 33% reported having “Good” or “Excellent” access, while roughly 27% indicated “No access at all” or “Limited access.” The majority selected “Moderate access,” suggesting that while some programs are available, they may not fully meet participants’ expectations.

Figure 5. Access to Community Programs in Respondents’ Areas (Unit: %)

2. Limited access – There are a few programs, but they are hard to reach or not useful.

3. Moderate access – Some programs are available, but they are limited or not always helpful.

4. Good access – I have access to useful community programs with some limitations.

5. Excellent access – I have easy access to a variety of helpful community programs.

The findings from this survey highlight both the potential and limitations of current community programs in addressing the needs of disconnected youth in the U.S. Results suggest that these programs can positively influence education and career development outcomes, particularly when young adults receive consistent support and perceive the programs as helpful. However, many respondents reported limited or no access to such programs, revealing gaps in availability and effectiveness. These insights point to a clear opportunity for targeted policy action to expand access, improve program quality, and ensure that support reaches the youth who need it most.

Reference

Crockett, A., & Zhang, X. (2023, April 6). Young adults are disconnected from work and

school due to long-term labor force trends. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Available at: https://www.dallasfed.org/cd/communities/2023/2303.

Seo, Frank. “Bridging Disconnection: Community Program Participation and Perceived Impact Among U.S. Youth.” Southern Ag Today 5(24.5). June 13, 2025. Permalink