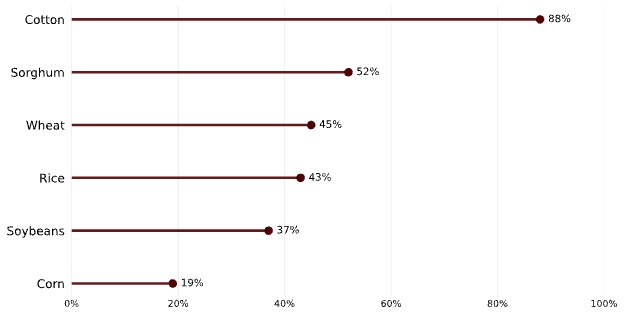

U.S. cotton is among the most export‑dependent agricultural commodities, with more than 80% of annual production moving into global markets rather than being used domestically (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2026a). Although China has not always been a consistent buyer, importing less than 15% of U.S. cotton exports in some years and more than 30% in other years, it has nevertheless remained a somewhat reliable partner, accounting for nearly 30% of U.S. cotton exports in more recent years (2020–2024) (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2026b).

Once the most important market for U.S. cotton, China has become a far less reliable partner in 2025, as recent import patterns show greater volatility and reduced engagement with the U.S. agricultural sector. In 2025, China’s purchases of U.S. cotton fell from $1.5 billion to just $0.2 billion, an 85% decline, while its import volume dropped at nearly the same rate, from 0.8 million metric tons (MMT) to 0.1 MMT. In contrast, exports to markets outside China expanded substantially over the same period. The value of U.S. cotton exports to non‑China destinations rose from $3.5 billion to $4.6 billion, a 32% increase, while quantities surged 51%, from 1.7 MMT to 2.6 MMT (Table 1) (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2026b).

Why did China sharply reduce its imports of U.S. cotton? While the trade war and subsequent political tensions certainly accelerated the decline, the underlying shift runs deeper than tariffs. China’s overall import strategy has fundamentally changed as its domestic cotton sector has undergone major structural adjustments since 2010. Over the past decade, China has increased production, drawn down its massive state-held stockpiles, and reduced its dependence on foreign fiber. Since 2021 alone, domestic output has risen by more than 30% (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2025a). As a result, China is increasingly able to meet the needs of its textile and apparel industry with domestic cotton rather than imports. Taken together, these developments suggest that China’s reduced reliance on U.S. cotton is not simply a temporary response to trade tensions but part of a longer-term realignment.

Table 2 makes clear that the steep decline in U.S. cotton exports to China was not simply the result of tariffs or bilateral tensions, but part of a much broader contraction in China’s overall import demand. China’s total cotton import value fell from $5.3 billion in 2024 to $1.9 billion in 2025, while import volumes dropped from 2.6 million to 1.1 million metric tons. Every major supplier experienced significant losses: Brazil’s shipments fell by more than 50%, India’s collapsed by over 90%, and Australia also recorded substantial reductions.

The across‑the‑board declines underscore a structural shift in China’s sourcing strategy rather than a U.S.-specific outcome.

Table 1. U.S. Cotton Exports: 2024 and 2025

| 2024 | 2025 | Change | % Change | |

| Value ($ billion) | ||||

| China | $1.5 | $0.2 | -$1.3 | -85.1% |

| Total (w/o China) | 3.5 | 4.6 | 1.1 | 32.0% |

| Total (w/ China) | 5.0 | 4.8 | -0.1 | -2.8% |

| Quantity (million metric tons) | ||||

| China | 0.8 | 0.1 | -0.6 | -84.6% |

| Total (w/o China) | 1.7 | 2.6 | 0.9 | 51.0% |

| Total (w/ China) | 2.5 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 9.6% |

| Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture (2026b) | ||||

Table 2. China’s Cotton Imports (Major Exporting Countries): 2024 and 2025

| 2024 | 2025 | Change | % Change | |

| Value ($ billion) | ||||

| Total | $5.3 | $1.9 | -$3.4 | -63.6% |

| Brazil | 2.2 | 0.8 | -1.4 | -63.4% |

| U.S. | 1.9 | 0.2 | -1.6 | -87.8% |

| Australia | 0.7 | 0.6 | -0.1 | -13.8% |

| India | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.1 | -91.1% |

| Turkey | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 3.7% |

| Quantity (million metric tons) | ||||

| Total | 2.6 | 1.1 | -1.5 | -59.2% |

| Brazil | 1.1 | 0.5 | -0.6 | -57.8% |

| U.S. | 0.9 | 0.1 | -0.8 | -86.8% |

| Australia | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.2% |

| India | 0.1 | 0.0 | -0.1 | -90.9% |

| Turkey | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | -4.1% |

| Source: Trade Date Monitor®(2026) | ||||

References

Trade Data Monitor®. (2026). https://tradedatamonitor.com/

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2026a). PSD Online. Foreign Agricultural Service. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/app/index.html#/app/advQuery

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2026b). Global Agricultural Trade System. Foreign Agricultural Service. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx

Muhammad, Andrew. “When China Stops Buying: Is this the New Reality for U.S. Cotton?” Southern Ag Today 6(9.4). February 26, 2026. Permalink