The September World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report indicates modest changes in supply and demand for corn and soybeans. The World Agricultural Outlook Board (WAOB) increased their estimated corn yield by 0.5 bushels per acre, offset by a decrease in carryover from the 2023 marketing year. Soybean demand also saw a slight increase of 2 million bushels. Both cotton and rice yields were cut; however, the lower yield expectations were offset by lower demand, resulting in no change to the projected season-average price.

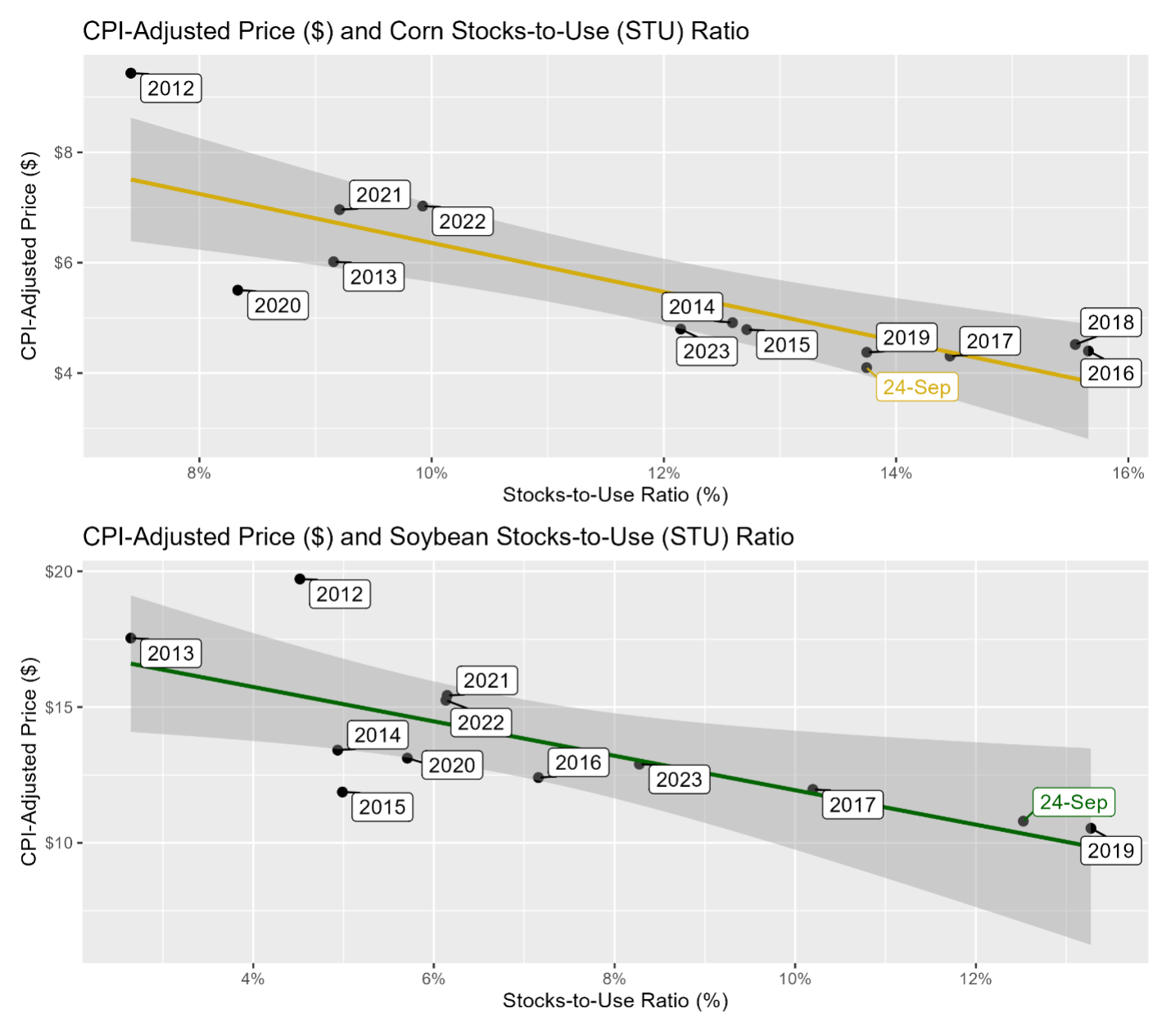

The remainder of this article focuses on corn and soybeans, which exceed trend yields by 2.6 and 1.2 bushels and represent a national high. Record yield expectations are driving stocks-to-use ratios (a key indicator of surplus) to levels much higher than in recent years. Consequently, the USDA has projected the marketing year average price for corn to be around $4.10 per bushel, while soybeans are expected to average $10.80 per bushel.

Currently, domestic consumption and exports of corn and soybeans appear to be stable. Crush (processing) and ethanol production are at or near record highs, while export demand is lower, but somewhat steady. Without a significant change in the yield estimate due to drought or overestimation, it is hard to envision a sharp price rise for the 2024/25 marketing year.

Figure 1 graphs stocks-to-use ratios and CPI- (inflation) adjusted season average prices for corn and soybeans with the September WASDE Estimates and associated trendlines (green and yellow with gray confidence intervals). CPI-adjusted corn prices are at their lowest level since at least 2011, and soybeans are nearing the lows seen in 2019. As a result, 2024 may be one of the toughest years for grain producers in the past decade, given the absence of a major event that could drive substantial price increases.

Figure 1: CPI Adjusted Price and Stocks to Use Ratio for Corn and Soybeans

Sources:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, World Agricultural Outlook Board. (2024, September 13). World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE). https://www.usda.gov/oce/commodity/wasde

Gardner, Grant. “Minimal Price Gains Amid Record Yields: A Tough Outlook for Grain Producers in 2024.” Southern Ag Today 4(38.3). September 18, 2024. Permalink