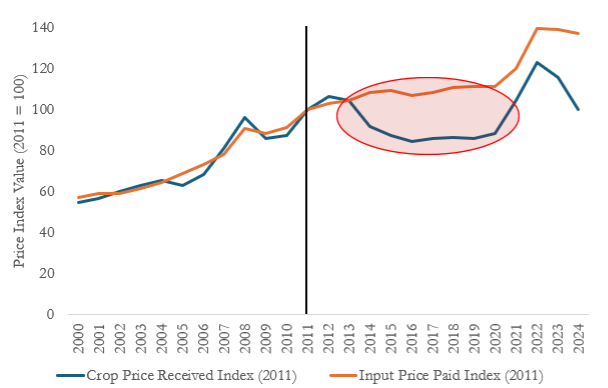

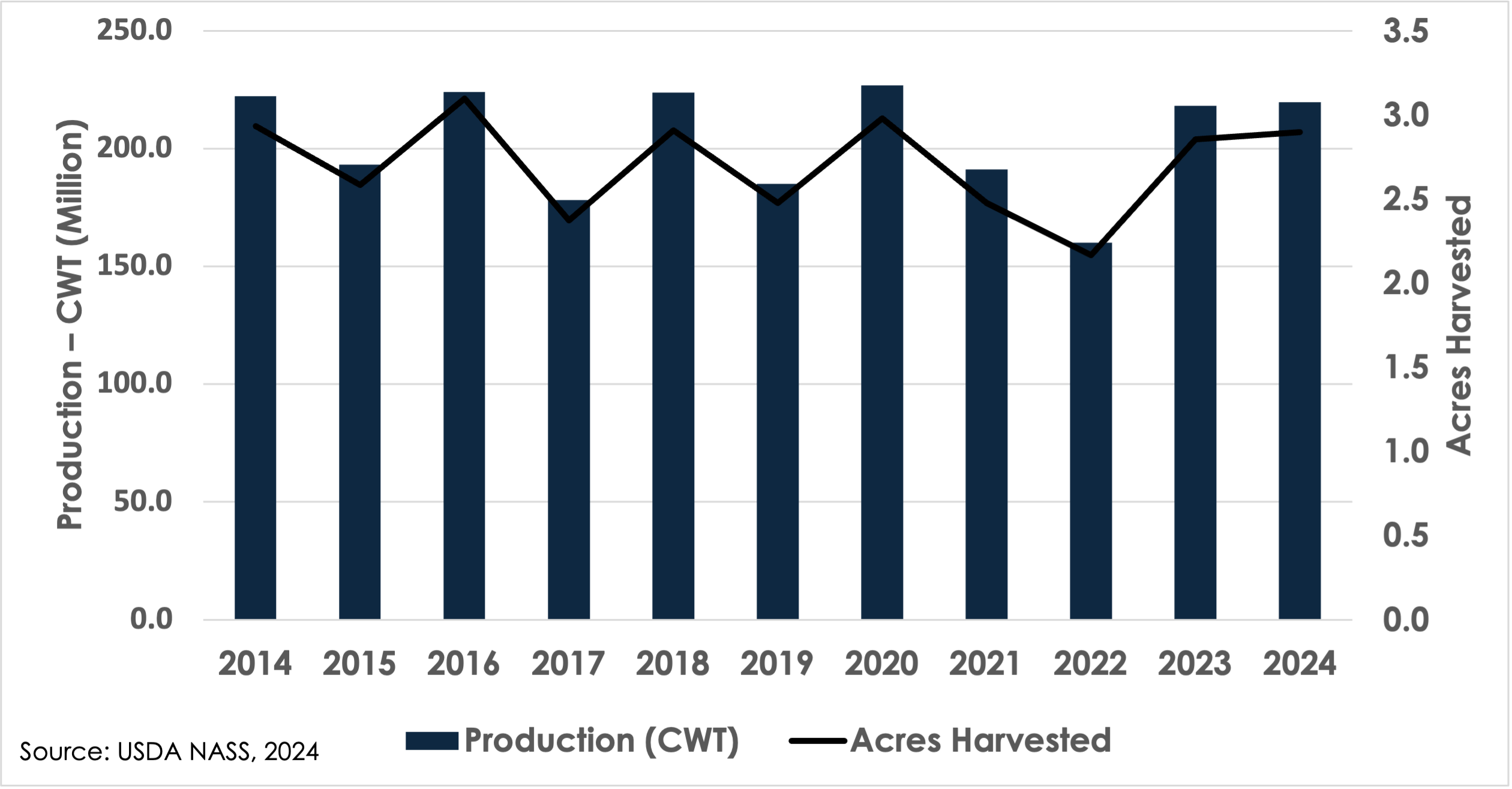

With several key moves during the 2024 rice market, and harvest behind us, we can let the dust settle and make some observations and conclusions as we look toward 2025. A major shift in domestic production patterns emerged in 2022; volatile input costs, triggered by the Russian-Ukraine War and supply chain disruptions, led to a decline in rice acreage as southern U.S. farmers opted to grow less input-intensive crops like soybeans and corn. These challenges were exacerbated by a severe drought in California that substantially reduced short/medium grain rice production. Rice production rebounded in 2023 and maintained that level in 2024, when more stable fertilizer prices shifted producers back to rice to counter the risk of lower prices, as was the case in other commodities (Figure 1). Recent conversations with agronomists indicate that U.S. rice farmers may maintain or expand rice acreage and production in 2025.

Figure 1. U.S. All Rice Class Production and Acres Harvested (2014 – 2024)

The November 2024 World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report indicates the current outlook for U.S. rice is for larger ending stocks, weaker exports and unchanged supplies and domestic use from October 2024 (USDA-AMS, 2024). All rice exports combined are lowered 1 million cwt to a total of 100 million. All rice ending stocks are increased 1 million cwt to 46.7 million, a 19% increase from the 2023/24 marketing year. The seasonal average farm price for long grain and southern short/medium grain is unchanged at $14.50/cwt, suggesting a cautious domestic response to the stock increases (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Rice Marketing Year Average Farm Prices (2020/21 – 2024/24F)

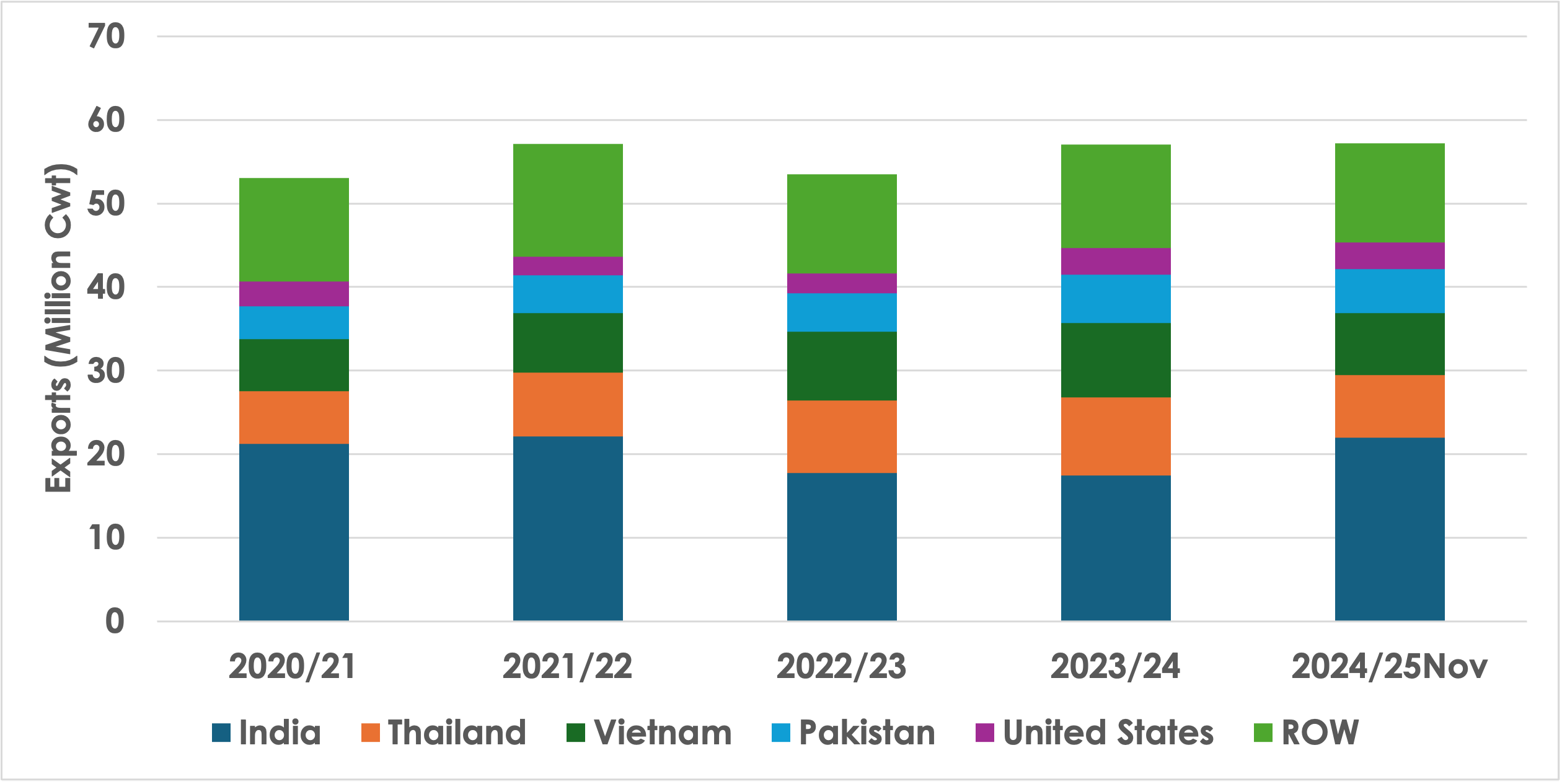

Internationally, it’s important to note the spread between India’s rice, Thailand/Vietnam rice, and U.S. milled rice. U.S. long grain is and has remained for several months at $800/metric ton, while Vietnam and Thailand are currently selling at $550 and $500/metric ton, respectively. The price gap widened following the September 2024 lift of India’s export ban on non-basmati milled rice. Currently, India has set the price floor at $490/metric ton. India’s return to the international market has forced Thailand and Vietnam to lower their prices by 10-13%, impacting demand for U.S. long grain rice in countries like Iraq. Iraq’s preference for cheaper rice from Asia, influenced by the price differential, has reduced demand for U.S. rice exports and poses a challenge for U.S. farmers (Childs and Jarrell, 2024).

Looking ahead, global rice exports for 2025 are expected to increase by 4% YoY, bringing total exports to 56.3 million metric tons. India is projected to reclaim much of their share, reaching a volume of 21 million tons. However, countries like Pakistan, Thailand, Vietnam, and the United States are expected to see a decline in export volumes (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Milled Rice Exports (2020/21 – 2024/25Nov)

References

United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Marketing Service. (2024). World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE-654). Retrieved November 9, 2024, from, https://www.usda.gov/oce/commodity/wasde/wasde1124.pdf

United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service – PSD Reports. (2024). World Rice Trade. Retrieved November 9, 2024, from, https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/app/index.html#/app/downloads

United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service. (2024). Rice Production and Acres Harvested. Retrieved October 2024, from, https://quickstats.nass.usda.gov/

Loy, R., and Hunter, B. (2024). The Disparity Between Crop Prices Received and Input Prices Paid.” Southern Ag Today 4(28.3). July 10, 2024. Available at, https://southernagtoday.org/2024/07/10/the-disparity-between-crop-prices-received-and-input-prices-paid/

Childs, N., & Jarrell, P. (2024). Rice outlook: October 2024 (Report No. RCS-24I). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. Retrieved November 2024, from, https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/outlooks/110219/rcs-24i.pdf?v=5219.8

Loy, Ryan. “Sifting through the Rice Market: Rising Supplies and Growing Competition.” Southern Ag Today 4(48.3). November 27, 2024. Permalink