To say that international trade has dominated the news in recent weeks would be an understatement. Last month, President Trump followed through on his promise to impose 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico, and an additional 10% on China. While Mexico—and to a lesser extent, Canada—received another temporary reprieve, the threat of tariffs still looms.

It is crucial to understand the potential impacts of these tariffs on U.S. agriculture. In his recent State of the Union Address, as well as in subsequent social media posts, President Trump claimed that the new round of tariffs would result in increased domestic agricultural sales. There is an element of truth to this claim. According to economic theory, tariffs can lead to a rise in domestic sales—if the imported product directly competes with a similar domestic product. However, this does not apply to commodities like soybeans or cotton, as the U.S. exports far more of these products than can be consumed domestically. For example, more than 70% of U.S. cotton production is exported. In fact, these sectors are particularly vulnerable because they are often the target of retaliatory tariffs. Also, any increase in domestic sales resulting from tariffs has less to do with firms facing less competition and more to do with the fact that tariffs lead to higher domestic prices. These higher prices, in turn, encourage more domestic producers to sell their products. While this benefits producers, it unfortunately disadvantages importing firms and consumers, with the disadvantages far outweighing any gains.

Imports should not be regarded solely as competition to American production. This perspective neglects the essential role imports play in meeting demands that exceed domestic capabilities. International trade is far more complex than the simplistic notion that “exports are good, imports are bad.”

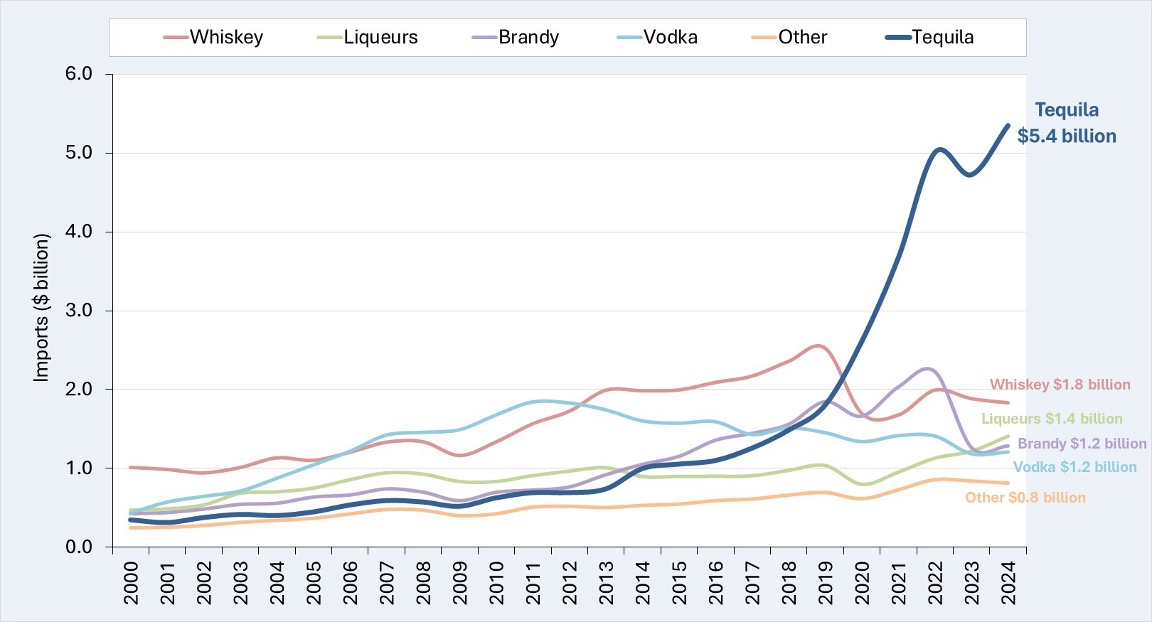

Tequila, an agricultural product imported entirely from Mexico and cannot be produced elsewhere, serves as a prime example for examining the harmful impacts of proposed tariffs. U.S. imports of distilled spirits have soared by over 300% since 2000, largely driven by the extraordinary growth in tequila imports. Between 2000 and 2024, tequila imports skyrocketed by 1,400%, rising from $350 million to $5.4 billion (Figure 1). In 2024, U.S. agricultural exports totaled $176 billion, while imports reached $214 billion, resulting in an agricultural trade deficit of $38 billion. Remarkably, tequila alone accounts for over 14% of this deficit, despite being a single, highly differentiated product. Over the past decade, our growing taste for tequila has driven a more than five-fold surge in demand and imports. Imagine the outrage if tequila imports were banned simply to address the agricultural trade deficit.

I recently conducted research on the impact of a 25% tariff on Mexico and Canada on U.S. imports of distilled spirits (https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.22034). My findings indicate that such a tariff would reduce imports by over $1 billion, far outweighing any potential tariff revenue gains. This overall decline is primarily driven by a significant drop in tequila imports, though imports of other spirits would also decrease due to complementarities in importing.

It could be argued that these losses would primarily impact the exporting country—Mexican tequila companies. However, this perspective overlooks the fact that U.S. tequila consumption also supports American bars, retailers, wholesalers, and distributors. When factoring in the downstream economic impact, the losses become even more substantial. Clearly, it would be difficult to prove that American largess is enriching Mexican agave farmers at the expense of U.S. agricultural producers.

Figure 1. U.S. Imports of Tequila and Other Spirits: 2000 – 2024

For more information:

Muhammad, A. (2025), Trump Tariffs 2.0: Assessing the Impacts on US Distilled Spirits Imports. Agribusiness. https://doi.org/10.1002/agr.22034

Muhammad, Andrew. “Rethinking Tariffs: Tequila Shows There’s More to Imports Than Competition.” Southern Ag Today 5(12.4). March 20, 2025. Permalink