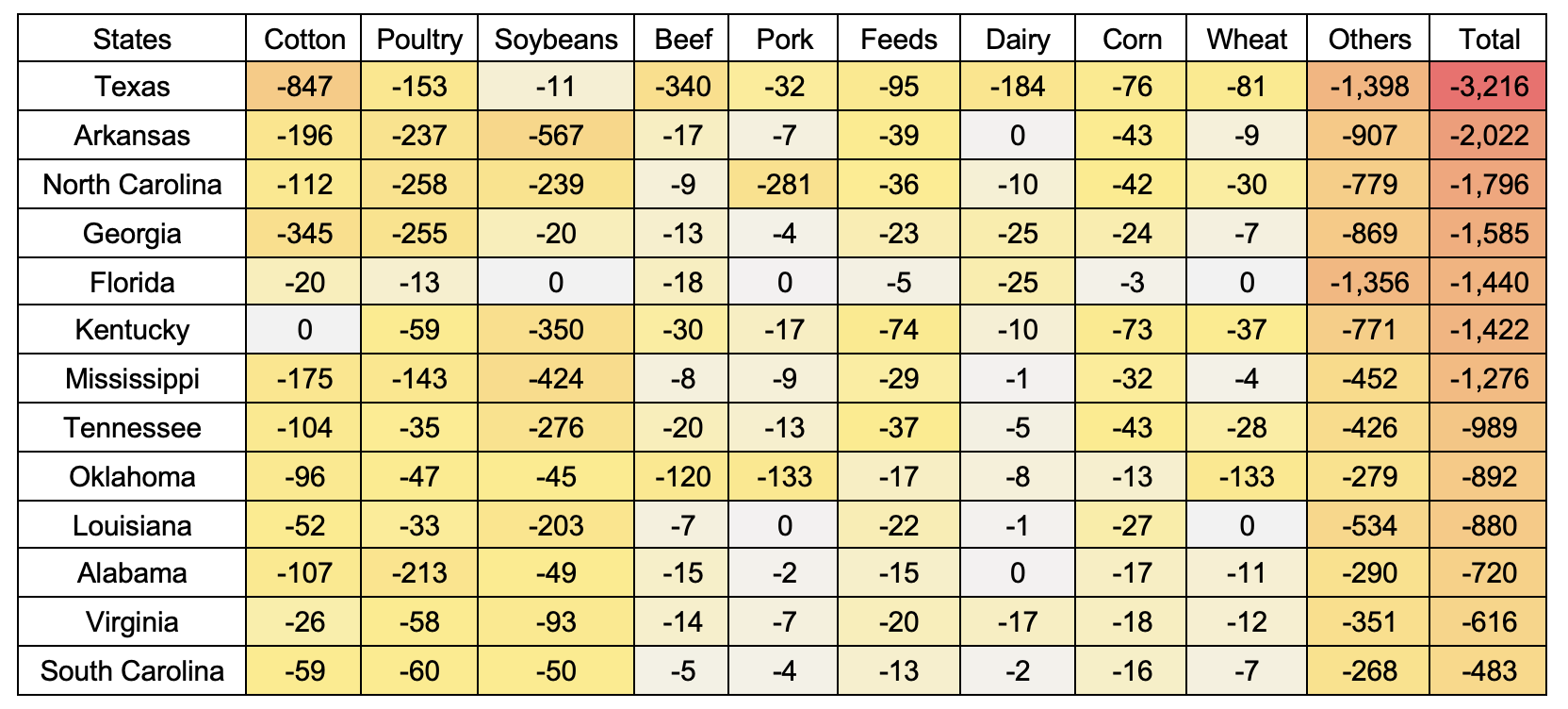

The recent Southern Ag Today policy/trade article on December 12 by Goyal et al discussed the state-level economic consequences for potential trade policy shifts following the 2024 U.S. presidential election. In summary, their analyses investigated the worst-case scenario if the US where to impose a 60% tariff on Chinese goods, including a 10% tariff on imports from other countries. Such an action, as indicated by Goyal et al, could result in a 60% tariff on US agricultural exports and further tariffs from other trading partners. Their projected export losses under this scenario for 2025 by commodity and state are replicated in Table 1 below:

| Table 1. State Level Shocks by Commodity Grouping Based on Worst-Case Scenario* | |||||||||||

| States | Cotton | Poultry | Soybeans | Beef | Pork | Feeds | Dairy | Corn | Wheat | Others | Total |

| TX | -$847 | -$153 | -$11 | -$340 | -$32 | -$95 | -$184 | -$76 | -$81 | -$1,398 | -$3,217 |

| AR | -$196 | -$237 | -$567 | -$17 | -$7 | -$39 | $0 | -$43 | -$9 | -$907 | -$2,022 |

| NC | -$112 | -$258 | -$239 | -$9 | -$281 | -$36 | -$10 | -$42 | -$30 | -$779 | -$1,796 |

| GA | -$345 | -$255 | -$20 | -$13 | -$4 | -$23 | -$25 | -$24 | -$7 | -$869 | -$1,585 |

| FL | -$20 | -$13 | $0 | -$18 | $0 | -$5 | -$25 | -$3 | $0 | -$1,356 | -$1,440 |

| KY | $0 | -$59 | -$350 | -$30 | -$17 | -$74 | -$10 | -$73 | -$37 | -$771 | -$1,421 |

| MS | -$175 | -$143 | -$424 | -$8 | -$9 | -$29 | -$1 | -$32 | -$4 | -$452 | -$1,277 |

| TN | -$104 | -$35 | -$276 | -$20 | -$13 | -$37 | -$5 | -$43 | -$28 | -$426 | -$987 |

| OK | -$96 | -$47 | -$45 | -$120 | -$133 | -$17 | -$8 | -$13 | -$133 | -$279 | -$891 |

| LA | -$52 | -$33 | -$203 | -$7 | $0 | -$22 | -$1 | -$27 | $0 | -$534 | -$879 |

| AL | -$107 | -$213 | -$49 | -$15 | -$2 | -$15 | $0 | -$17 | -$11 | -$290 | -$719 |

| VA | -$26 | -$58 | -$93 | -$14 | -$7 | -$20 | -$17 | -$18 | -$12 | -$351 | -$616 |

| SC | -$59 | -$60 | -$50 | -$5 | -$4 | -$13 | -$2 | -$16 | -$7 | -$268 | -$484 |

| *60% tariff on US agricultural exports plus additional tariffs from other trading partnersSource: Southern Ag Today, December 12, 2024 (Goyal et al) | |||||||||||

Of interest would be the total economic impacts (including multiplier effects) based on this worst-case scenario. Using the direct impacts from Table 1 (excluding the category grouping “Other” because of uncertainty what that grouping entails), an input-output model (IMPLAN) can provide this information. IMPLAN model output includes descriptive metrics of the economy such as total industry output (a measure of economic activity) and total value added. Total industry output (TIO) is defined as the value of production by industry per year. Total value added or gross regional product is defined as all income to workers paid by employers; self-employed income; interests, rents, royalties, dividends, and profit payments; and excise and sales taxes collect by business from individuals. It is equivalent to a state’s Gross Regional Product, which is analogous to Gross Domestic Product for the entire U.S.

Based on the IMPLAN state model runs using 2023 data and reporting the economic information in 2025$, the backward linked[1] results are displayed in Table 2. The direct impacts for economic activity, -$8.7 billion, are what was presented by Goyal et al. The indirect impacts, which account for the decrease in economic activity from input suppliers, total -$3.1 billion. Decreased household spending, or the induced impacts, totals -$2.0 billion. The total economic impacts are close to -$14.0, a -$5.2 billion difference from the direct impact of -$8.7. The decrease in Gross Regional Product totaled -$6.6 billion. Tax impacts as a result of Goyal et al’s worst-case scenario analysis totals -$992.0 million.

| Table 2. Estimated Economic Impacts from Worst-Case Scenario (2025$)* | |||

| TIO (EconomicActivity) | Gross Regional Product | Taxes | |

| (billion $) | (million $) | ||

| Direct1 | -$8.7 | -$3.7 | -$342.7 |

| Indirect2 | -$3.1 | -$1.6 | -$373.8 |

| Induced3 | -$2.0 | -$1.2 | -$275.5 |

| Total4 | -$13.9 | -$6.6 | -$992.0 |

| *60% tariff on US agricultural exports plus additional tariffs from other trading partners1Direct effects are those what was presented by Goyal et al.2Indirect effects are those attributable to the input supplying businesses (e.g., expenditures on raw materials, supplies, and other operating expenses).3Induced effects are created as the new income generated by the direct and indirect effects is spent and re-spent within the region.4Total is the sum of the direct, indirect, and induced effects. | |||

This short, quick analysis gives an example of how an initial change in direct spending has ripple effects throughout the economy. Not only are the commodities in question affected, but input suppliers and household spending also feel the negative shock in this example. Consequently, tax receipts are affected as well.

[1]Describes the interconnectedness of an industry with its supply chain and “looks backward” to its necessary intermediate inputs to produce its output. In input-output modeling, Type I multipliers measure these backward linkages, whereas the Type SAM multipliers expand on these linkages to include household spending (IMPLAN Glossary “Backward Linkage”, 2017).

References

Goyal, R., S. Steinbach, Y. Yildirim, and C. Zurita. 2024. “State-Level Effects of Potential Trade Policy Shifts on Southern U.S. Agriculture.” Southern Ag Today. December 12.

IMPLAN Group LLC, IMPLAN System (2023 data and Cloud Platform V. 24.6 Release), 16905 Northcross Dr., Suite 120, Huntersville, NC 28078. Available at implan.com.

Menard, R. Jamey. “Estimated Total Economic Impacts from Trade Policy Shifts-Worst-Case Scenario Revisited.” Southern Ag Today 5(4.4). January 23, 2025. Permalink