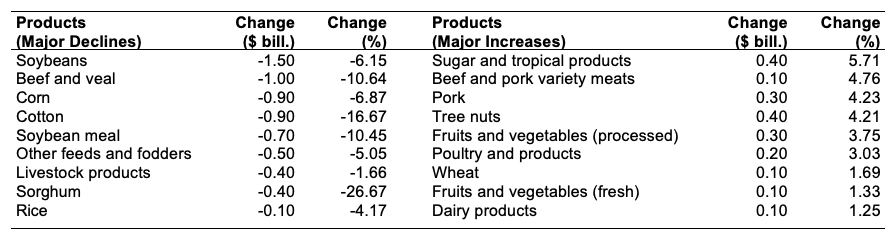

The outcome of the upcoming presidential election could reshape U.S. trade policy, directly impacting Southern U.S. agriculture. With its dependence on exporting commodities like soybeans, cotton, and poultry, the region faces uncertainty as potential policy shifts loom. Historically, Southern agriculture has been sensitive to changes in trade policies, as seen during recent trade conflicts like the U.S.-China trade war, which led to substantial income losses for farmers and ranchers across the region. Understanding how those new trade policy scenarios, as summarized in Table 1, might unfold is crucial for preparing Southern farmers and agricultural businesses for a turbulent period in global trade.

One possible scenario comes from the Biden administration’s 2024 decision to impose a 20% (trade-weighted) tariff on Chinese electric vehicles and other critical sectors. In response, we could see commodity-specific tit-for-tat trade retaliation from China in 2025, potentially involving a 20% tariff on U.S. agricultural exports. While this scenario is aggressive, it would likely remain a bilateral conflict between the U.S. and China, much like the 2018-2019 trade dispute that significantly impacted U.S. farmers, particularly those in the Southern states.

A more extreme scenario would be for the U.S. to impose a 60% tariff on Chinese goods and a 10% tariff on imports from all other countries. Those who believe that taking a protectionist stance on trade is the best way to increase U.S. jobs have suggested this trade policy approach. However, such a move would almost certainly provoke a strong reaction, with China likely imposing a 60% tariff on U.S. agricultural products and other countries also raising their tariffs on U.S. goods by 10%. The U.S. South’s heavy reliance on foreign markets could create severe disruptions in global trade, with the region’s agriculture being particularly hit.

A third scenario could involve the U.S. Congress revoking China’s Permanent Normal Trade Relations (PNTR) status, which some lawmakers believe is necessary for national security and economic reasons. This could result in a 9.5% increase in tariffs on Chinese goods. In this scenario, China is expected to respond with an equivalent tariff on U.S. agricultural exports. Although this scenario focuses more on the U.S.-China relationship, it presents significant risks for Southern agriculture.

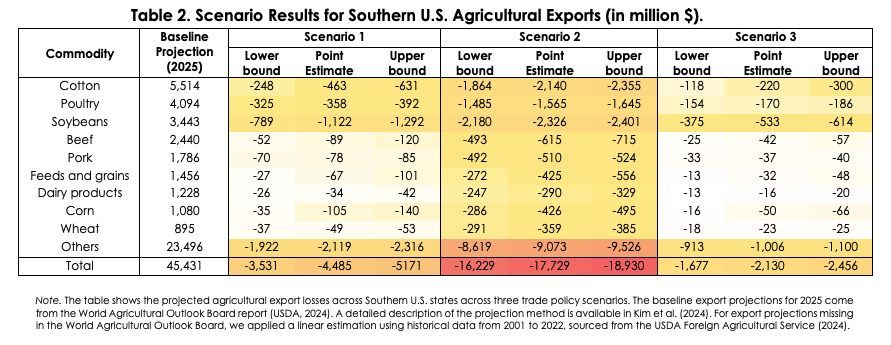

Table 2 presents each scenario’s projected export losses. Southern agriculture is closely tied to global markets, with key exports like soybeans, cotton, poultry, and livestock playing a pivotal role. Take soybeans, for example. This crop is central to agriculture in Arkansas, Mississippi, and Kentucky. Under the first scenario, we estimate soybean exports could fall by 32.6%, or about $1.2 billion. The third scenario presents a more moderate decline of 15.5%, equating to a loss of approximately $0.6 billion. If the second, more extreme scenario were to unfold, soybean exports could drop by a staggering 67.6%, which translates to a loss of $2.4 billion. Such a decline would likely lead to excess soybeans in domestic markets, pushing prices down and putting financial pressure on farmers.

Cotton, another critical crop for Southern states like Texas, Georgia, and Arkansas, would also face serious challenges. Under the first scenario, cotton exports could decrease by 8.4%, leading to a $0.5 billion loss. The third scenario predicts a 4% decrease, amounting to a loss of around $0.2 billion. The drop could be as high as 38.8% in the second scenario, or $ 2.1 billion. These losses could have ripple effects throughout the regional economy, squeezing farm incomes and adding financial stress. The poultry industry, vital to Georgia, North Carolina, and Alabama, would not be spared. In the first scenario, poultry exports might shrink by 8.8%, while in the second scenario, the decrease could reach 38.2%. This would amount to billions in lost revenue, hitting rural economies hard.

Potential trade policy scenarios following the U.S. presidential election could considerably affect Southern U.S. agriculture. While the exact outcomes will depend on the policies that are ultimately implemented, the risks to the Southern agricultural economy are clear. By diversifying export markets, investing in value-added agriculture, strengthening domestic markets, and advocating for supportive trade-relief programs, Southern U.S. states could better position themselves to deal with the challenges posed by these potential shifts in trade policy. Southern agriculture must be prepared and adaptable in the face of these uncertainties, ensuring it can thrive in an increasingly competitive global market disrupted by protectionist trade policies.

Learn More

Kim, D., Steinbach, S., Yildirim, Y., & Zurita, C. (2024). Understanding Trade Strategy Impacts on Soybean Exports and Farm Income in North Dakota. CAPTS White Paper 2024-01. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4920301.

Goyal, Raghav, Sandro Steinbach, Yasin Yildirim, and Carlos Zurita. “Trade Policy Scenarios after the U.S. Presidential Election and What They Could Mean for Southern U.S. Agriculture.” Southern Ag Today 4(44.4). October 31, 2024. Permalink