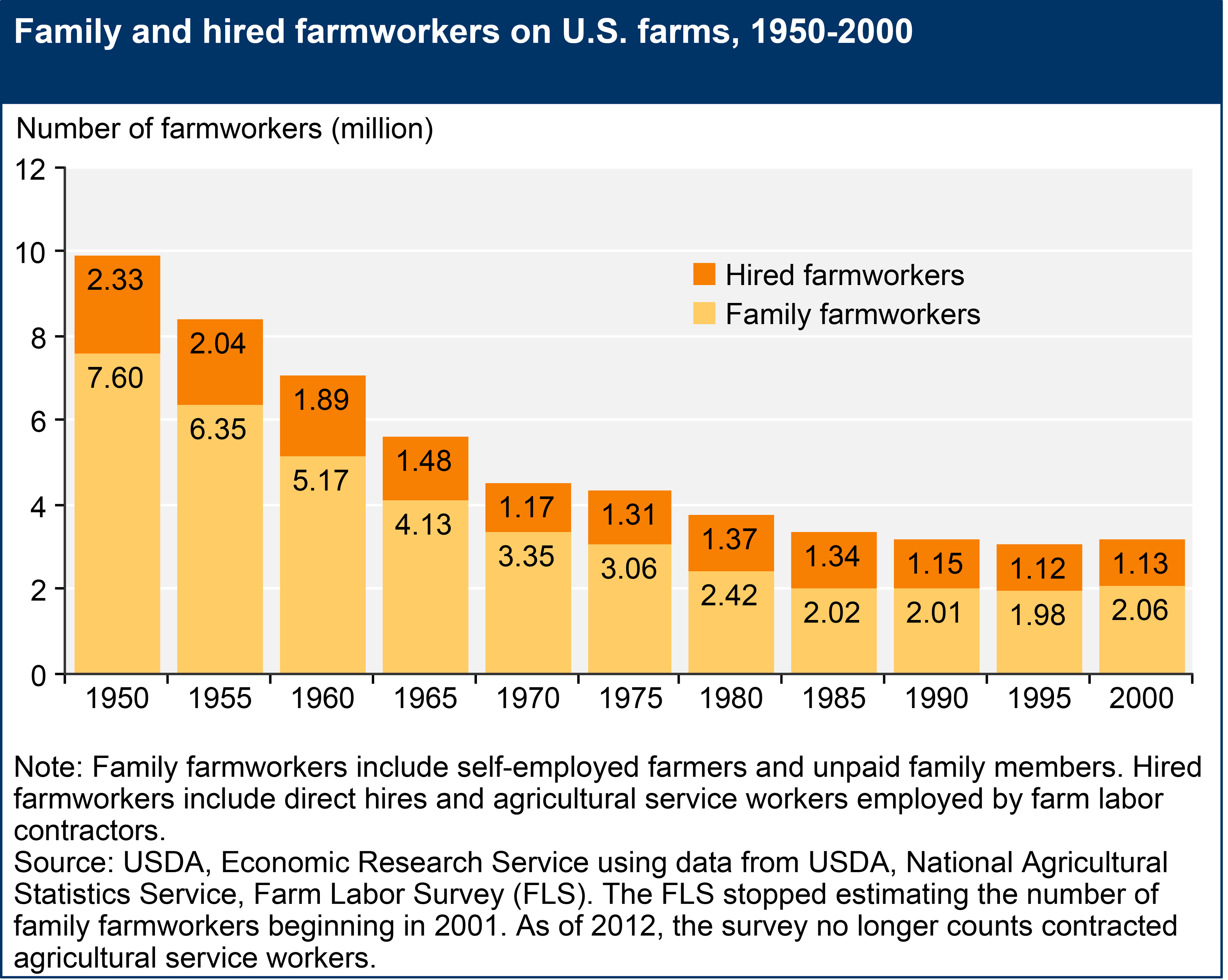

In a previous article titled Challenges for U.S. Fruits and Vegetables we discussed some of the challenges that the U.S. fruit and vegetable industry faces. Labor cost and availability is identified as the main challenge that the U.S. fruits and vegetable industry faces. Dependance on foreign-born farm labor is around 70 percent. Therefore, in order to address the shortage of farm labor, the H-2A Temporary Agricultural Program—often called the H-2A visa program— was created in 1986.

The H-2A provides a legal means to bring foreign-born workers to the United States to perform seasonal farm labor on a temporary basis, for a period of up to 10 months. Employers in the H-2A program must demonstrate, and the U.S. Department of Labor must certify, that efforts to recruit U.S. workers were not successful. Employers must also pay a State-specific minimum wage rate, which may not be lower than the average wage rate for crop and livestock workers surveyed in the Farm Labor Survey (FLS) in that region in the prior year, known as the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR). Figure 1 shows the AEWR by state and it is obvious that those rates are much higher than the federal minimum wage as well as any state minimum wage. In addition, H-2A employers must provide transportation, housing, food, insurance, and visa application fees, among other expenses that could add between 35% to 40% of the AEWR rate, i.e., $21.77 in Texas, $20.68 in Florida and $27.65 in California. Industry experts shared that agricultural wage rates in Mexico averages around $20.59 in Colima and $23.53 in Sonora per day, or $2.57 and $2.94 per hour for an 8-hour workday, respectively. Finally, as the labor shortage keeps getting worse, producers could be getting into wage bidding wars to secure farm labor during peak season, increasing their labor cost even more.

Even though labor cost takes a major toll on the fruits and vegetable industry, it is left with little to no options. Not only is the share of the labor cost higher than other agricultural industries, but also labor is scarce. According to ERS (2023), one of the clearest indicators of the scarcity of farm labor is the fact that the number of H-2A positions requested and approved has increased more than sevenfold in the past 17 years, from just over 48,000 positions certified in fiscal 2005 to around 371,000 in fiscal year 2022. The average duration of an H-2A certification in fiscal 2022 was 5.65 months, implying that the 371,000 positions certified represented around 175,000 full-year equivalents. A certified job does not necessarily result in the issuance of a visa; in fact, in recent years only about 80 percent of jobs certified as H-2A have resulted in visas. Around 300,000 visas were issued in fiscal 2022 by the Department of State.

References

Economic Research Service (ERS). “Farm Labor.” Accessed February 2024. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-labor/. Updated August 7, 2023.

Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS). Global Agricultural Trade System (GATS). Online database. https://apps.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx. Online public database accessed February 2024.

Ribera, Luis, and Landyn Young. “Challenges for U.S. Fruits and Vegetables (Part 2).” Southern Ag Today 4(32.4). August 8, 2024. Permalink