By: National Agricultural Law Center Attorney Staff

Agricultural law in 2025 was marked by developments with lasting implications for producers, agribusinesses, and rural communities. Attorneys at the National Agricultural Law Center have identified the following major trends that shaped the year.

- State restrictions on foreign ownership of farmland continued to expand. Six states amended existing laws and four enacted new restrictions, at the same time courts considered constitutional challenges. Recent cases involving Florida and Texas laws were dismissed on standing grounds, leaving the broader legal questions unresolved.

- Federal agencies proposed sweeping changes to environmental law. In November, EPA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers released a proposed revision to the definition of “waters of the United States” under the Clean Water Act, aligning it with the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision limiting jurisdiction to “relatively permanent” waters with a continuous surface connection. Meanwhile, the Fish and Wildlife Service and National Marine Fisheries Service issued four proposed rules revising Endangered Species Act implementation, including species listing, critical habitat designation, interagency consultation, and elimination of FWS’s blanket 4(d) rule for threatened species.

- Congress also reshaped hemp regulation through appropriations legislation that closed the “hemp loophole” created by the 2018 Farm Bill. The law redefined hemp based on total THC content and excluded synthesized cannabinoids such as delta-8 and delta-10, significantly affecting an industry largely focused on cannabinoid production when the changes take effect in November 2026.

- Food policy gained attention through the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) movement, led federally by HHS and echoed by states. Legislative efforts included new food labeling requirements, restrictions on ingredients in school meals, bans on synthetic food dyes, and proposals to limit SNAP-eligible foods through USDA waivers.

- Pesticide litigation remained a major issue, particularly whether the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) preempts state “failure to warn” tort claims. While manufacturers argue federal label approval preempts liability, plaintiffs contend FIFRA requires adequate health warnings. The Supreme Court may resolve the issue in Monsanto Co. v. Durnell, with the Solicitor General urging review and preemption.

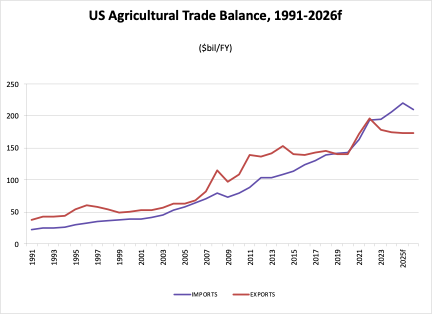

- Trade policy also shifted as the Trump Administration increased tariffs using the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). This unprecedented use of IEEPA authority was challenged in V.O.S. Selections, Inc. v. Trump, argued before the Supreme Court in November, while potential trade agreements remain preliminary.

- Labor issues intensified with changes to the H-2A foreign agricultural worker program. A court vacated the 2023 Adverse Effect Wage Rate rule, prompting reversion to an older formula and subsequent issuance of a new interim final rule, now subject to legal challenge.

- EPA actions on pesticide registration and labeling continued, including issuance of its Insecticide Strategy, proposed dicamba label revisions, and litigation over herbicides and neonicotinoids that could affect future availability.

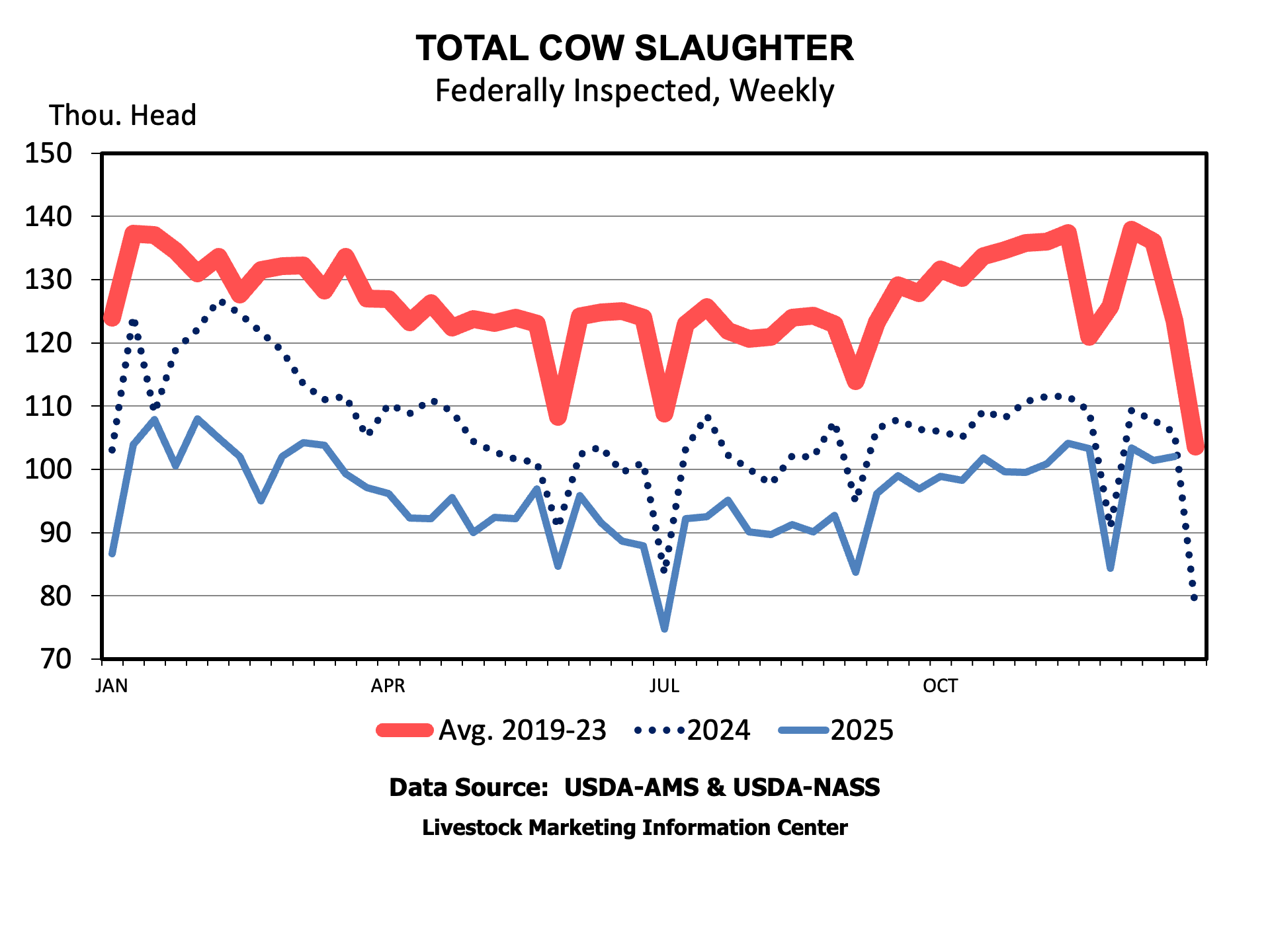

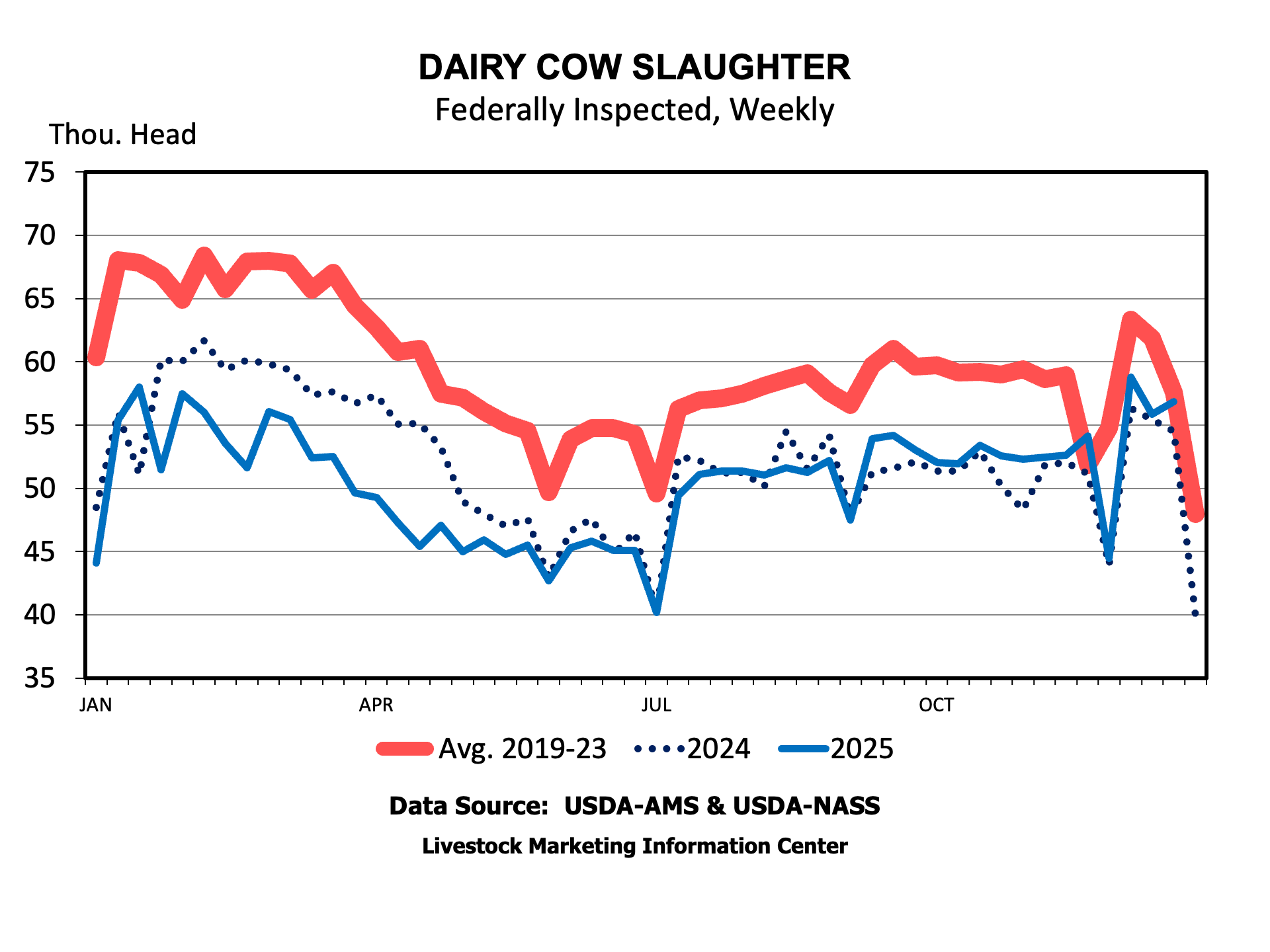

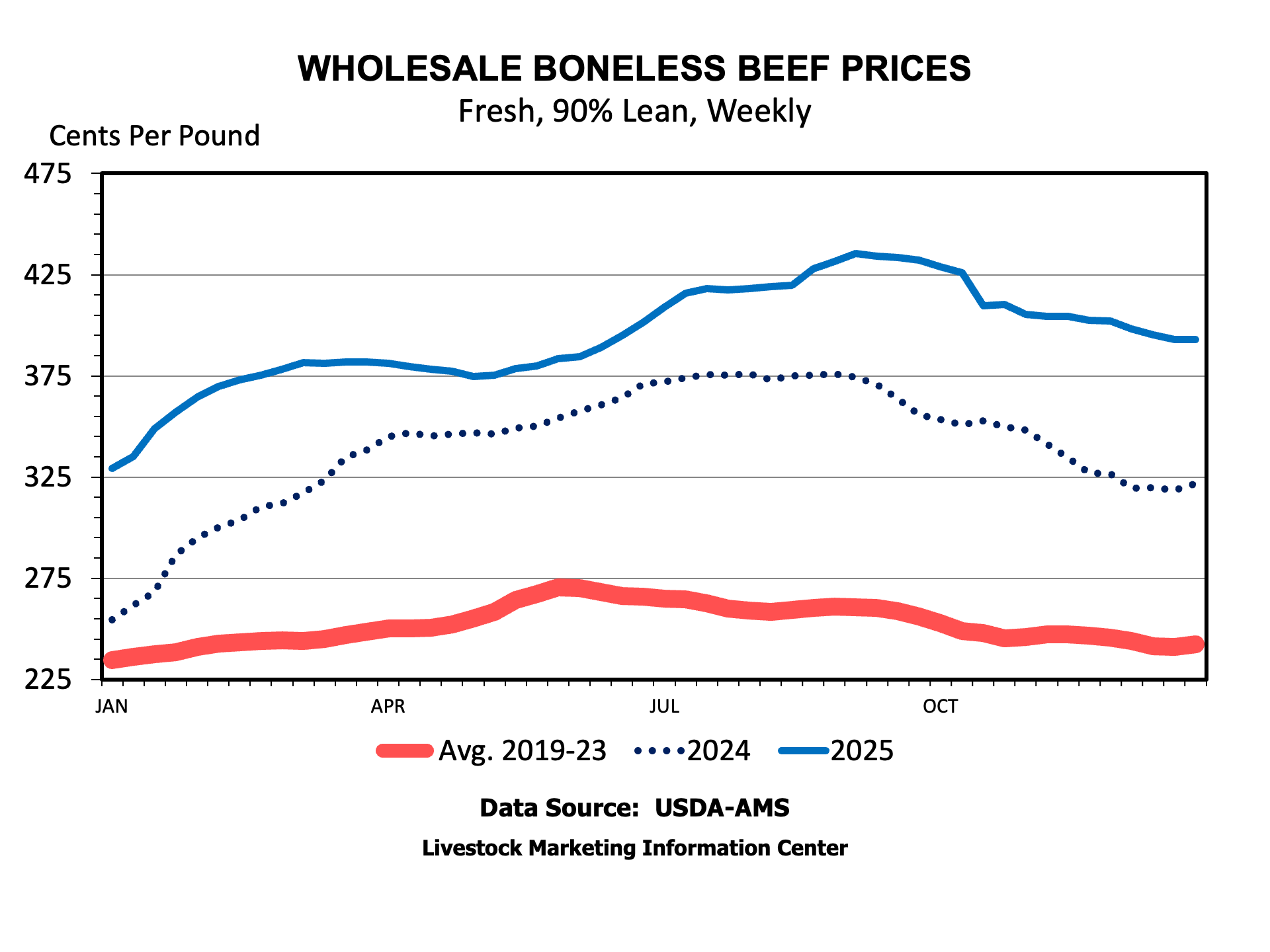

- Competition concerns spanned the agricultural supply chain. DOJ and USDA investigated meatpacker conduct, while scrutiny expanded to seed, chemical, and fertilizer markets. In December, President Trump ordered agencies to investigate anticompetitive behavior across food industries.

- H.R.1—the One Big Beautiful Bill Act—reauthorized key farm bill programs, increased reference prices and payment limits, strengthened crop insurance, and made major tax provisions permanent, including an inflation-indexed increase to the estate tax exemption.

Looking ahead to 2026, many of the top issues from this past year will continue to develop. Additional areas to watch are challenges to Prop 12 and related statutes on issues of preemption, interest in state legislatures around the labeling and sale of cell-cultured proteins, and updates to the Colorado River operating plan. We also expect to see issues related to financial distress in the farm economy and state level responses, such as amending or creating grain indemnity laws and financial assistance programs. A link with more information about each of these stories is available at https://bit.ly/48SRX0p.