This year, there have been several Southern Ag Today articles discussing the impacts of tight fed cattle supplies on prices, cattle on feed, slaughter weights, and total beef production (Anderson 2025a, Anderson 2025b, Maples 2025). On November 21, Tyson announced that they would be closing their Lexington, Nebraska plant in January 2026. Following the announcement, there have been a lot of questions revolving around the impact of the closure on national slaughter capacity utilization (CU).

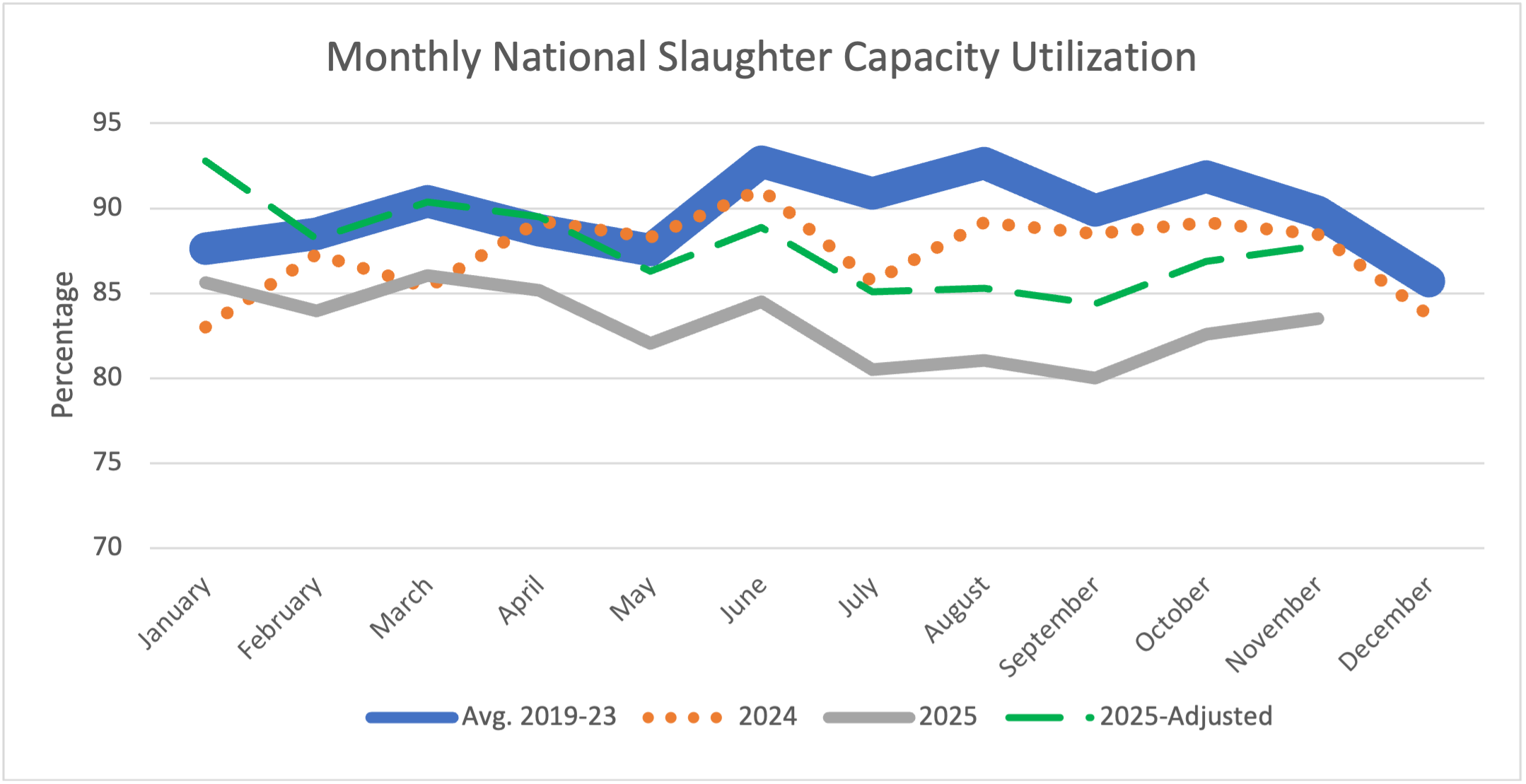

The Lexington, Nebraska plant had an approximate daily capacity of 5,000 head. That equates to approximately 20% of Tyson’s daily capacity (25,800 head/day) as a company. In Martinez et al. (2023), we showed a measure of national slaughter capacity utilization, which measures the ratio of operational cattle slaughter capacity over total physical capacity. To estimate the impact of the closure on the national CU, we use 2025’s monthly slaughter with an adjusted 2025 slaughter CU. The adjusted CU is simply adjusting the national CU with the daily 5,000 head taken out. Figure 1 displays the monthly national federally inspected (FI) slaughter capacity utilization with the previous 5-year average (thick blue line), 2024 (orange dotted line), 2025 (grey thin line), and 2025-Adjusted (green dashed line).

Figure 1. Monthly National Federally Inspected Slaughter Capacity Utilization

The adjusted capacity utilization is closer to the previous 5-year average. Evaluating data through November, the average for the 5-year average was 90.1% while the 2025 and 2025-adjusted average through November are 83.1% and 87.7%, respectively. In November, slaughter capacity utilization averaged 83.5%, which was lower than November 2024 (88.4%), the previous 5-year average (89.8%), and the 2025-adjusted (87.8%).Overall, 2025 has seen declining fed cattle numbers in the cattle on feed reports and higher fed cattle prices, leading to low or negative packer margins. While the supply chain is offsetting tight cattle supplies with larger carcasses, the closure of the Lexington plant certainly signals there is excess capacity at this time. This is the first large scale plant to close since 2013, when Cargill closed their Plainview, TX plant, which was also during a time when cattle supplies were tight. There have been reports that Tyson is looking to buy that Plainview plant. Additionally, there are some plants that are reported to come online in 2026 and 2027. It is fair to question if the adjusted capacity utilization is a new norm, or simply a short run adjustment by the supply chain.

References

Anderson, David. “Fewer Marketings, Tighter Beef Supplies.” Southern Ag Today 5(26.2). June 24, 2025.

Anderson, David. “Working Less on Friday!” Southern Ag Today 5(21.2). May 20, 2025.

Maples, Josh. “Cattle Prices Hit New Highs and Carcass Grading Trends Over Time.” Southern Ag Today 5(19.2). May 6, 2025.

Martinez, C., Li, P., Boyer, C. N., Yu, T. E., & Maples, J. G. (2023). Beef price spread relationship with processing capacity utilization. Journal of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jaa2.48

Martinez, Charley, and Parker Wyatt. “The Impact of Tyson’s Closure on Beef Slaughter Capacity Utilization.” Southern Ag Today 5(49.2). December 2, 2025. Permalink