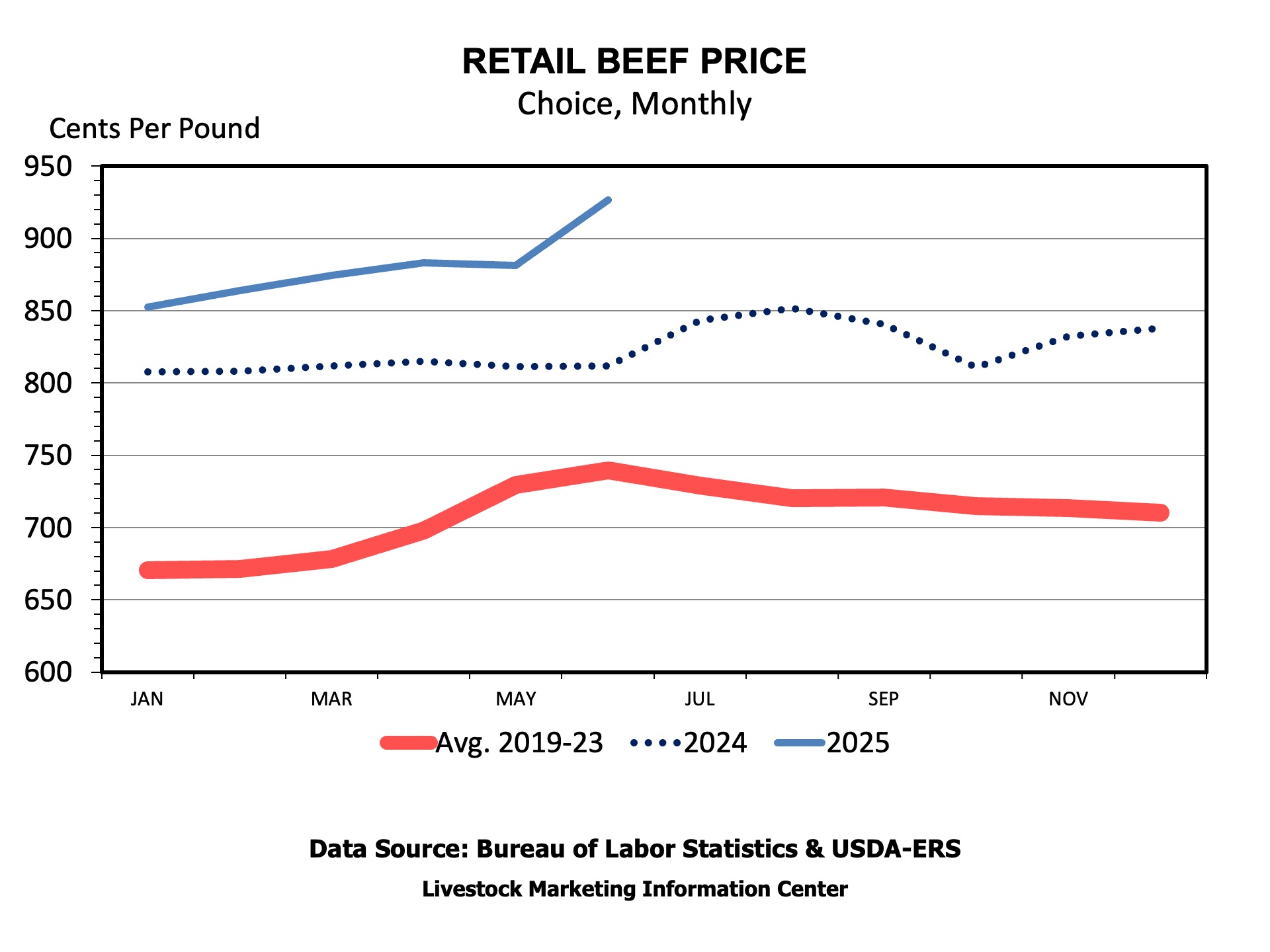

The record high retail beef price reported by the most recent Consumer Price Index (CPI) has prompted a lot of calls about why prices are record high and whether there is any relief in sight. While we often write about the great cattle prices for producers who are selling, there is a flip side, and that is consumers who are buying beef.

Reduced slaughter and beef production, especially in the second quarter of the year, cut supplies just as grilling season heated up seasonal beef demand. The combination led to a spike in wholesale prices and retail beef prices.

Is there a chance for consumers to see falling retail beef prices in the coming months? Normal seasonal production and demand would suggest prices falling from recent highs. Evidence from the wholesale beef market over the last couple of weeks indicates lower prices.

Starting with the cutout, the Choice boxed beef cutout has declined each week since it hit a record high weekly average value of $394 per cwt 4 weeks ago. Each of the seven primal cuts that make up the cutout has declined in price over this period.

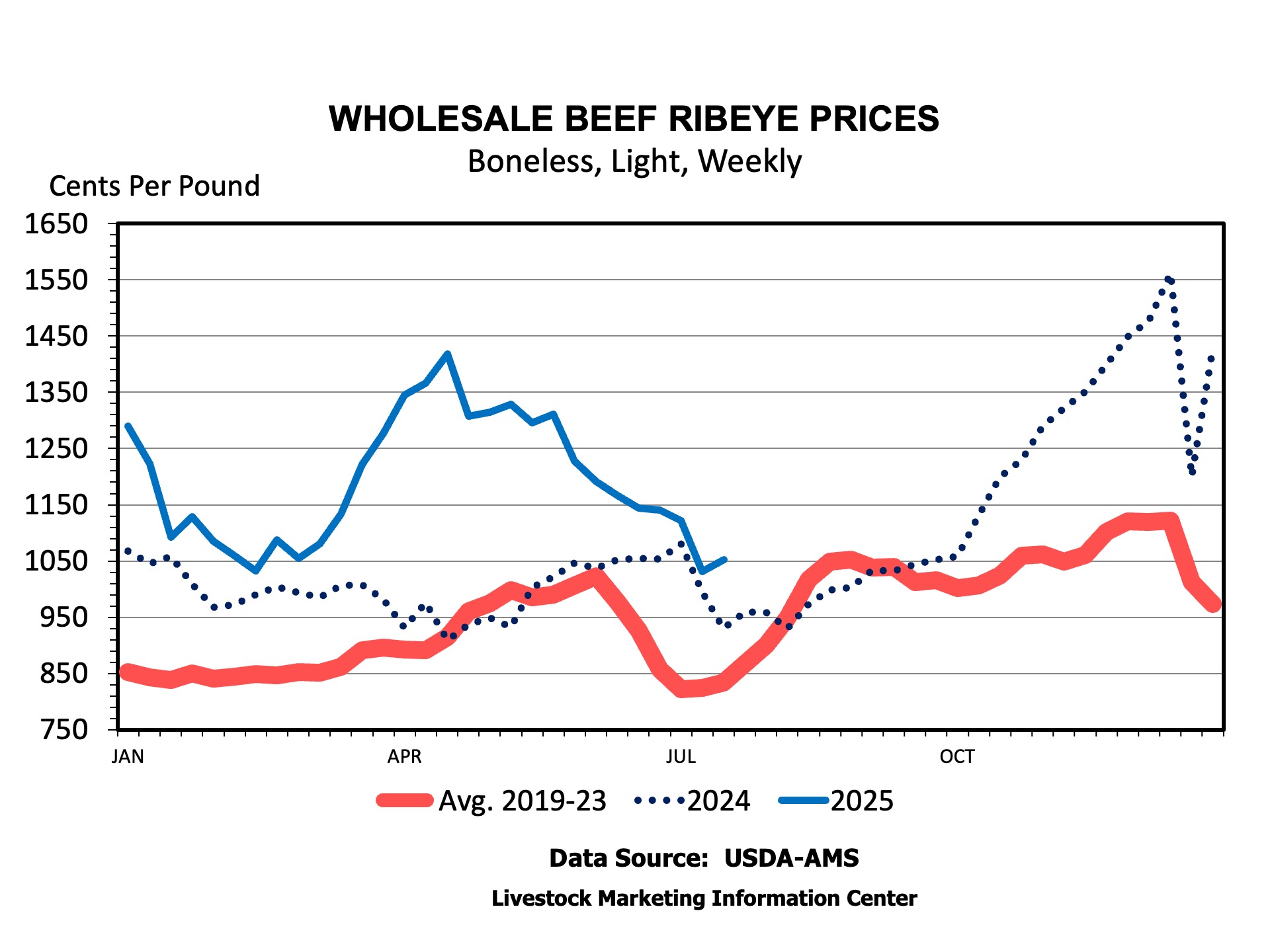

Ribeye steaks exhibit the normal seasonal pattern that peaks early in grilling season, then declines after Memorial Day. Ribeyes hit their annual peak price in late Fall as holiday demand drives them higher. Following the pattern, wholesale beef ribeyes peaked in price at $14.18 per pound. They have since declined to $10.50 per pound, only slightly ahead of last year.

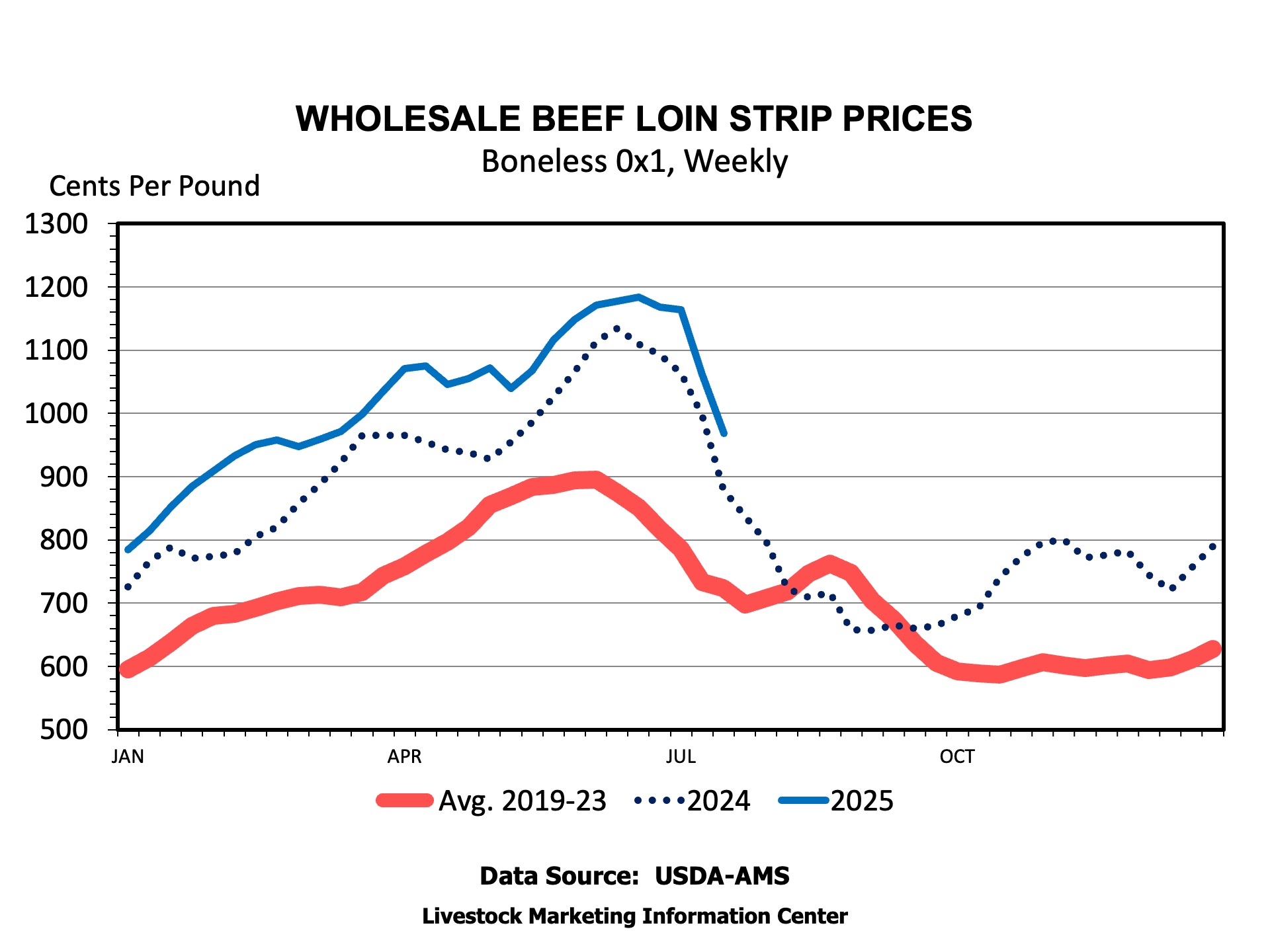

Loin strips usually hit their annual wholesale price peak leading up to July 4th. They hit $11.84 per pound in June and have since dropped to $9.68 per pound. The price remains higher than last year, but wholesale spot market prices are coming down.

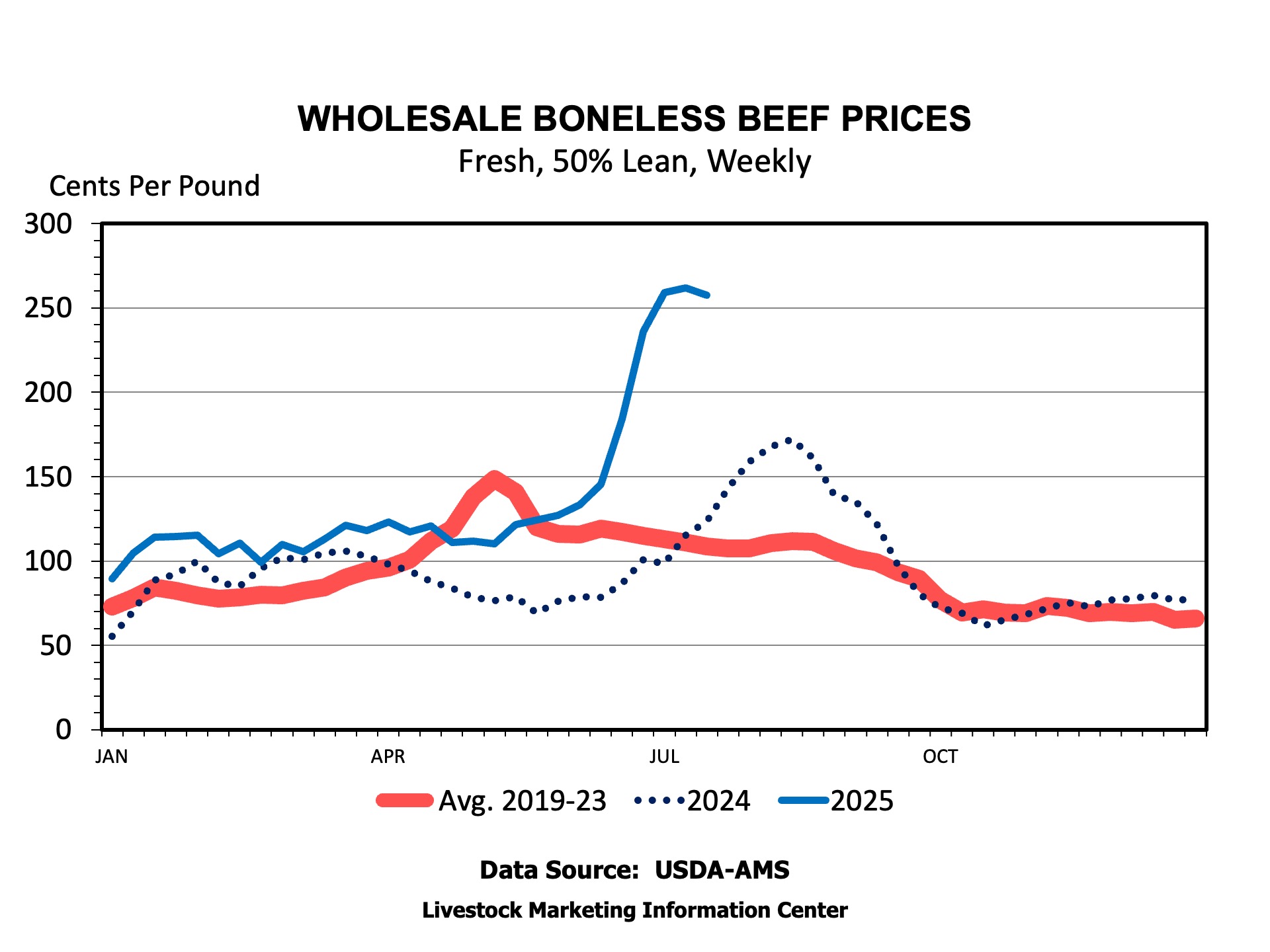

Wholesale 90 and 50 percent lean boneless beef prices continued to increase into July. The 50 percent lean price hit an all-time record of $2.62 per pound. Lean boneless beef is particularly impacted by fed beef supplies, which have been cut due to declining slaughter and seasonally lower weights. Boneless beef prices tend to decline seasonally after mid-year as we get past the grilling season rush in demand.

Seasonal price patterns would suggest that there is a chance for a little bit of relief from record high beef prices. But, only if we compare to the peak price this summer. Wholesale beef prices are already declining.

There is a time lag from lower wholesale prices showing up at retail, but lower wholesale prices combined with normal seasonality of various cut prices should lead to the expectation of falling prices in the coming months. But, it’s not likely that prices will decline below year ago levels.

A Preview

USDA will release the July Cattle on Feed report on Friday. While market analysts expect lower placements, marketings, and cattle in feedyards than a year ago, the really interesting number will be the number of heifers on feed on July 1. The heifers on feed will provide some insight into heifer retention. Also, look for placements in Texas due to the ban on Mexican feeder cattle. The lack of spayed heifers coming from Mexico is important in evaluating the number of heifers on feed.

Anderson, David. “Any Relief in Sight for Consumers?” Southern Ag Today 5(30.2). July 22, 2025. Permalink