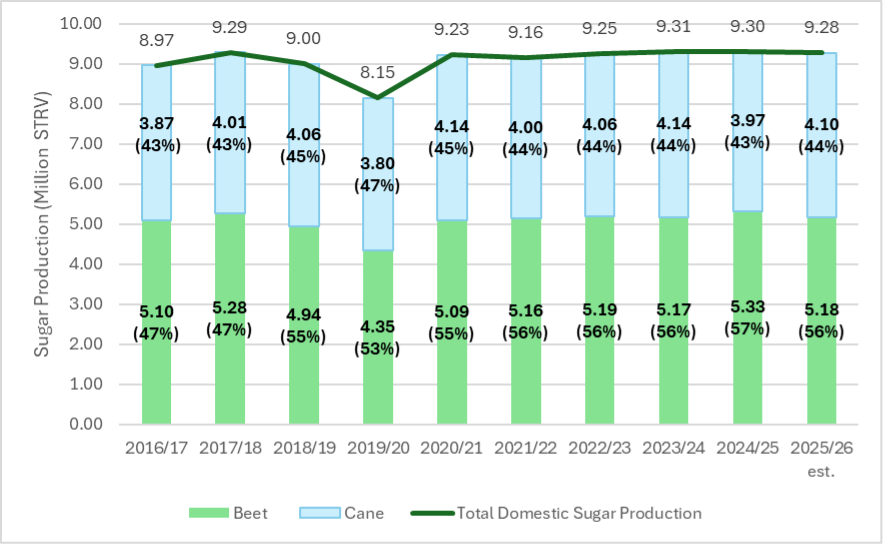

On May 12, 2025, the USDA released its World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (2025) report which provides the first 2025/26 fiscal year (FY) estimate of United States sugar production. United States domestic sugar production, which consists of sugar extracted from both sugarbeets and sugarcane, is estimated at 9.285 million short tons raw value (STRV) for the 2025/26 FY (USDA WASDE, 2025). Domestic beet sugar production is estimated at 5.180 million STRV, or 56% of total domestic production, and domestic cane sugar production is estimated at 4.105 million STRV, or 44% of total domestic production (Figure 1).

Total domestic use of sugar is predicted to be 12.355 million STRV which includes estimated domestic sugar production of 9.285 million STRV, U.S. sugar imports of 2.475 million STRV, and net stocks usage (beginning stocks minus ending stocks) of 0.596 million STRV (USDA WASDE, 2025). Thus, net stocks usage plus domestic sugar production is estimated to account for about 80% of the domestic use of sugar.

The estimated FY 2025/26 domestic sugar production (9.285 million STRV) represents a 26,000 STRV reduction from last year’s total domestic production of 9.311 million STRV (Figure 1). The 2025/26 FY has an estimated slight increase in cane sugar production that is offset by a decrease in beet sugar production, ultimately resulting in the slight year-over-year decrease in overall domestic sugar production.

Beet sugar production is estimated at 5.180 million STRV, a 154,000 STRV decrease (2.9%) from the year prior. Sugarbeets are produced in the Upper Midwest, Great Lakes, Great Plains, and Far West regions of the country. United States estimated 2025/26 FY sugarbeet planted area (1.104 million acres) is based on the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) (2025) March Prospective Plantings report. The estimated harvested area (1.081 million acres) is derived using a 10-year average of harvested-to-planted ratio. The sugarbeet shrink (6.76%) and recovery rate (14.78%) are both projected based on the 10-year national average.

Sugarcane is now produced in only two states- Florida and Louisiana. Cane sugar output is forecast at 4.105 million STRV, up 128,000 STRV (3.2%) from the year prior. Louisiana’s output is projected at 2.088 million STRV, reflecting six consecutive years of increase, and four years of surpassing Florida sugar production. Sugarcane acres in Louisiana have been increasing due to the attractiveness of sugar compared to other alternative crops, availability of custom harvest groups, and acreage expansion northward in the central region of the state. Florida’s cane sugar production is projected at 2.017 million STRV (USDA WASDE, 2025).

Figure 1. United States sugar production by source, 2016/17 FY through estimated 2025/26 FY.

Like many other agricultural sectors, the sugar sector has faced challenges. Namely, the tightening of operating margins due to rising costs of production (Deliberto and DeLong, 2024a) and flat or falling prices (Deliberto, DeLong, and Fischer, 2024b). This is most evident in the recent closures of sugar processing facilities in several states. Since 2000, roughly 40% of United States sugar mills, refineries, and sugarbeet factories have closed (i.e., 29 closures with 42 remaining open) (American Sugar Alliance, 2025; Louisiana Sugarcane Industry, 2025; Fischer, Outlaw, Raulston, and Herbst, 2022).

Most recently, there have been three notable closures. In 2023, the Sidney Sugar Company in Montana closed due to falling prices for sugarbeets (Western Ag Network, 2023). Next in 2024, the Rio Grande Valley Sugar Growers, Incorporated ceased operations (Food Business News, 2024). The facility terminated operations due to Mexico’s failure to comply with the provisions of the 1944 Water Treaty between the U.S. and Mexico that governs water sharing between the two nations on the Colorado River and the Lower Rio Grande. Most recently, it was announced that the last remaining sugarbeet processing facility in California will be decommissioned at the end of this season – the Spreckels Sugar Company, Incorporated in Brawley, California (Southern Minnesota Beet Sugar Cooperative, 2025).

In recent months, U.S. wholesale prices for beet and cane sugar have been falling (USDA Economic Research Service, 2025). Coupled with the rising costs of producing sugarbeets and sugarcane and processing them into sugar, this has created very tight operating margins for sugar producers (Deliberto and DeLong, 2024a). Looking ahead to the next growing season, farmers are optimistic that a new Farm Bill will strengthen the farm safety net and that growing conditions will be favorable for sugarbeets and sugarcane.

References

American Sugar Alliance. (2025). Sugar’s Coast-to-Coast Reach. Retrieved from: https://sugaralliance.org/us-sugar/sugars-coast-to-coast-reach.

Deliberto, M., and K.L. DeLong. (2024a). “Examining Sugarcane and Sugarbeet Production Costs.” Southern Ag Today. Retrieved from: https://southernagtoday.org/2023/12/11/examining-sugarcane-and-sugarbeet-production-costs/.

Deliberto, M., K.L. DeLong, and B. Fischer. (2024b). “Analyzing World and U.S. Sugar Price Dynamics.” https://southernagtoday.org/2024/05/20/analyzing-world-and-u-s-sugar-price-dynamics/.

Fischer, B.L., J.L. Outlaw, J.M. Raulston, and B.K. Herbst. (2022). “Economic Impact of the U.S. Sugar Industry.” Retrieved from: https://sugaralliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Sugar-Report.pdf.

Food Business News. (2024). Retrieved from: https://www.foodbusinessnews.net/articles/25615-last-sugar-cane-grower-in-texas-to-close.

Louisiana Sugarcane Industry. Production Data 1984-2023. Retrieved from: https://amscl.wpenginepowered.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Production-Data-1984-to-2023.jpg.

Southern Minnesota Beet Sugar Cooperative. (2025). Southern Minnesota Beet Sugar Cooperative to Decommission Spreckels Sugar Company, Inc. in California. Retrieved from: https://www.smbsc.com/ourstory-2/SMBSCMediaReleaseReSpreckelsSugarCompany2025.04.22.pdf.

USDA Economic Research Service. (2025). World, U.S., and Mexican Sugar and Corn Sweetener Prices. Tables 5 and 5a. Retrieved from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/sugar-and-sweeteners-yearbook-tables.

USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS). (2025). Prospective Plantings. Retrieved from: https://usda.library.cornell.edu/concern/publications/x633f100h.

USDA World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates. (2025). Retrieved from: https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/general-information/staff-offices/office-chief-economist/commodity-markets/wasde-report.

Western Ag Network. (2023). “Sydney Sugars to Begin Closure Procedures in April.” Retrieved from: https://westernagnetwork.com/sidney-sugars-to-begin-closure-procedures-in-april.

Deliberto, Michael, and Karen L. DeLong. “The 2025 Sugar Market Domestic Supply and Outlook.” Southern Ag Today 5(22.3). May 28, 2025. Permalink