The May 2025 World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) is a highly anticipated report as it offers the first official USDA estimates of the new crop marketing year (USDA, 2025). For 2025/2026, the estimates show a divergence of fundamental factors in the U.S. grain markets. Estimated days of use on hand at the end of the marketing year (a stocks-to-use ratio calculated by dividing ending stocks by average daily use) are projected to increase in 2025/2026 compared to 2024/2025 for corn, wheat, and rice. Conjointly, the season average farm price is projected lower for these three grains. For soybeans, days of use on hand are forecast to decrease and the farm price is forecast to increase compared to last year.

Based on the Prospective Plantings report back in March, corn acres for 2025 are projected at 95.3 million, up from 90.6 million in 2024. USDA’s yield estimate for 2025 is a record high 181.0 bushels per acre. This combines for a record corn crop of 15.820 billion bushels. Add in 1.415 billion bushels of beginning stocks and the corn supply in the 2025/2026 marketing year is a record 17.206 billion bushels, up 3.6% from last year.

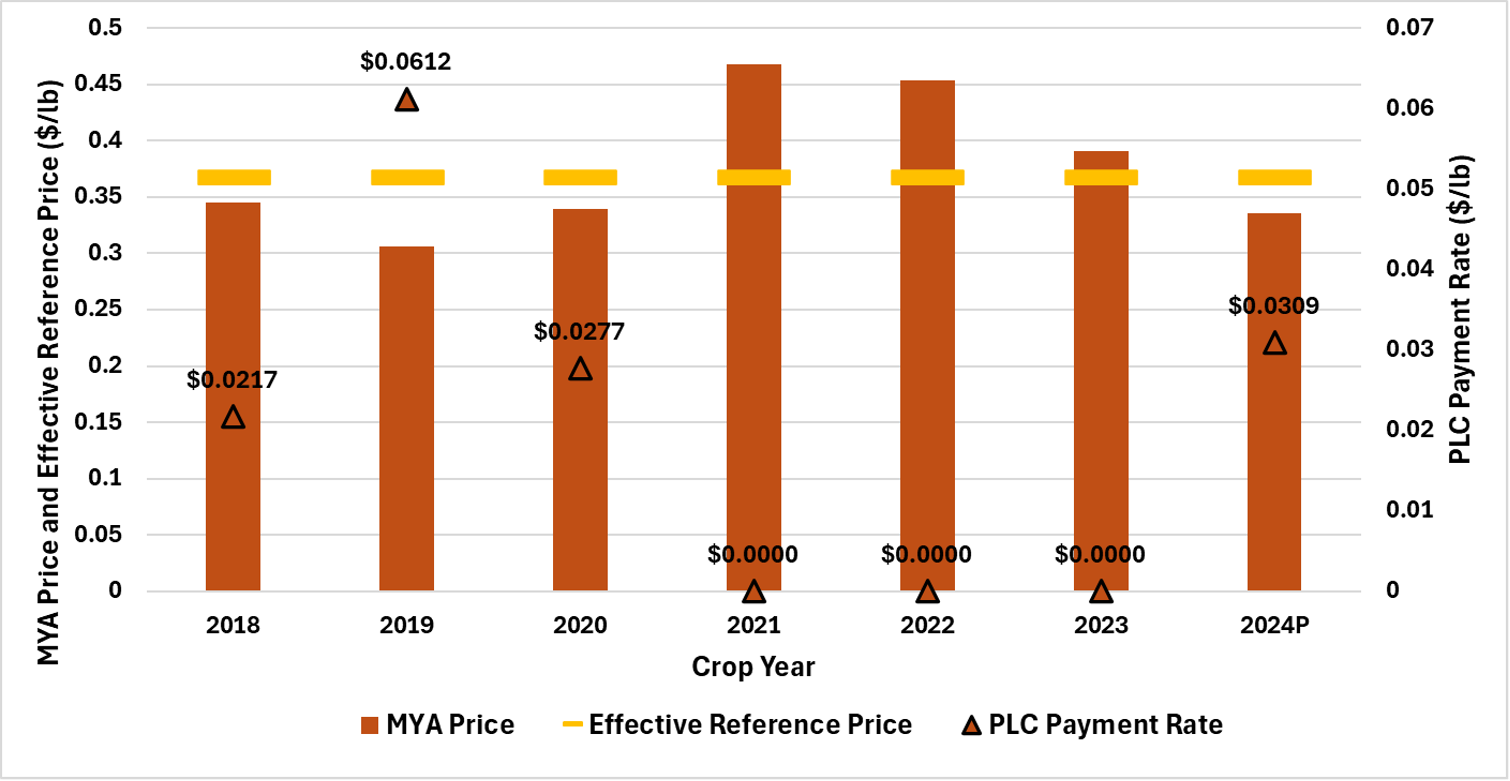

U.S. corn use is projected at record levels as well with increases in feed and exports. However, the increase in corn supply exceeds the increase in use, resulting in an increase in ending stocks. Days on hand increased by an 8.6-day supply, and the season average farm price is down from $4.35/bu last year to $4.20/bu. With a PLC reference price in 2025 of $4.26/bu, that would earn a 6-cent-per-bushel payment.

Soybean acres for 2025 are estimated at 83.5 million, down from 87.1 million in 2024. But with a record forecast yield of 52.5 bushels per acre, production in 2025 is down only 26 million bushels from 2024. Soybean use is forecast to increase by 31 million bushels on increased domestic crushings. Ending stocks are expected to decrease by 55 million bushels, and days of use on hand are expected to decline by 4.8 days. The season average farm price is projected to increase by 30 cents per bushel to $10.25.

U.S. wheat production is estimated to be little changed from the 2024 crop with the decrease in acres mostly offset by a higher yield estimate. Impacting the wheat supply for 2025/2026 is an increase in beginning stocks and a decrease in projected imports (-30 million bushels). Wheat use is projected lower on a decrease in exports of 20 million bushels. This raises the wheat ending stock estimate by 82 million bushels, increases carryover to a 172-day supply, and lowers the season average farm price from $5.50/bu last year to $5.30/bu. With a $5.56/bu reference price, this would generate a PLC payment of 26 cents per bushel.

The U.S. rice supply in 2025/2026 is projected higher, as an increase in beginning stocks offsets a small decline in production. Use is up 1 million hundredweight with an increase in domestic use and a decrease in exports. This leaves ending stocks up 3.5 million hundredweight and days on hand higher by 3.2. The farm price is down $2 per hundredweight to $13.20, below the PLC reference price of $14.00.

Of course, much can change between these early season estimates and final crop production and use numbers. Weather, trade policies, the economy, global grain fundamentals, and other factors foreseen and unforeseen, will evolve and emerge to shape grain prices. The May WASDE is an important benchmark to assess and estimate the impact of these changes and forces as the season unfolds.

Table 1. May 2025 WASDE Numbers for U.S. Grains (corn, soybeans, and wheat in millions of bushels; rice million hundredweight) and 2025 PLC Reference Prices and Estimated Payment Rate.

| Crop | Corn | Soybeans | Wheat | Rice | |||||||

| mil bu | change* | mil bu | change* | mil bu | change* | mil cwt | change* | ||||

| Beginning Stocks | 1,415 | -348 | 350 | +8 | 841 | +145 | 45.0 | +5.2 | |||

| Production | 15,820** | +953 | 4,340 | -26 | 1,921 | -50 | 219.3 | -2.8 | |||

| Total Supply | 17,260** | +605 | 4,710 | -24 | 2,882 | +64 | 313.5** | +3.5 | |||

| Total Use | 15,460** | +220 | 4,415 | +31 | 1,959 | -18 | 266.0** | +1.0 | |||

| Ending Stocks | 1,800 | +385 | 295 | -55 | 923 | +82 | 47.5 | +2.5 | |||

| Days on Hand | 42.5 | +8.6 | 24.4 | -4.8 | 172.0 | +16.7 | 65.2 | +3.2 | |||

| Price $/bu or $/cwt | |||||||||||

| Farm Price | $4.20 | -$0.15 | $10.25 | $0.30 | $5.30 | -$0.20 | $13.20 | -$2.00 | |||

| PLC Reference Price | $4.26 | $9.26 | $5.56 | $14.00 | |||||||

| PLC payment rate | $0.06 | $0.00 | $0.26 | $0.80 | |||||||

*change 2025/26 marketing year compared 2024/25 marketing year.

**record high

Reference

USDA, Office of the Chief Economist. World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates, May 12, 2025. Available online at https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/general-information/staff-offices/office-chief-economist/commodity-markets/wasde-report.

Welch, J. Mark. “Recap of the May WASDE for U.S. Grains.” Southern Ag Today 5(20.3). May 14, 2025. Permalink